Photos by Summy Lam, Club Director of Marketing

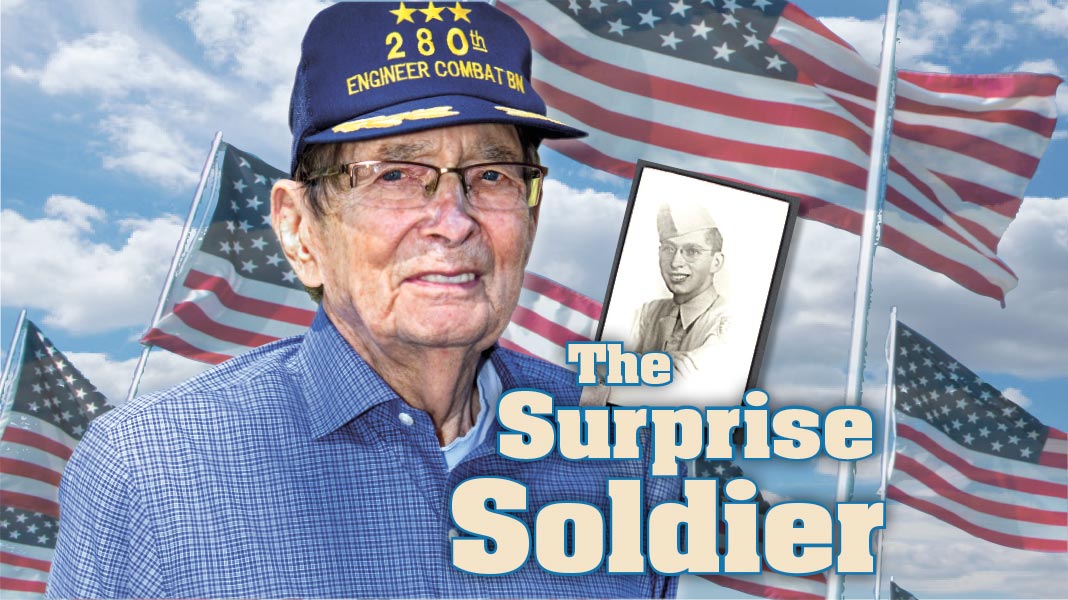

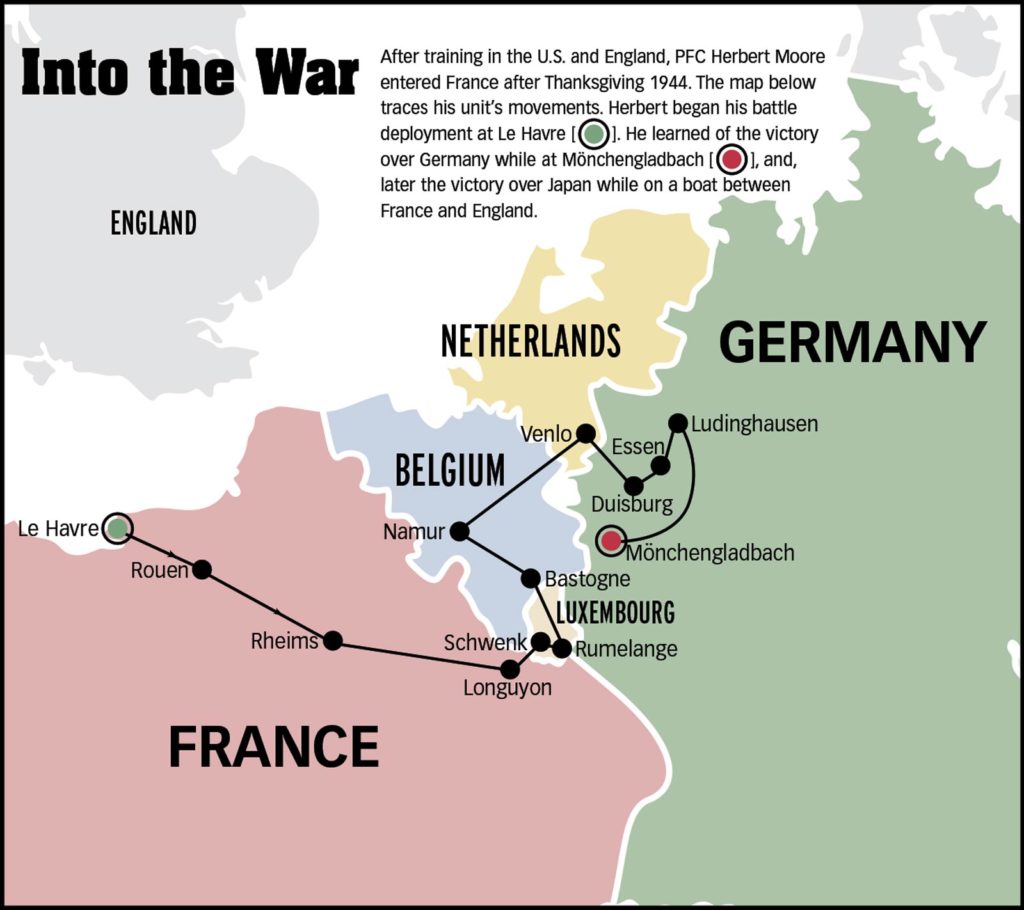

Herbert Moore, 95, Retired, Controller’s Office, trained as a World War II Army accountant. But history had other ideas: He deployed instead into the Battle of the Bulge sweeping for mines, building bridges and fixing countless roads for the advancing Allied troops. Here’s his story.

Back in 1943, Herbert Moore of Detroit, Mich., tried to enlist into the U.S. Army in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack at the end of 1941. But he had a bad eye, they said, so he joined the ROTC at the University of Michigan. He was told he could not continue in the ROTC program because of his eyesight.

He was drafted in his sophomore year. “I couldn’t enlist, but I could be drafted,” he laughs. His service to the country was going to be in financial management as an accountant. He trained to do that in at Ft. Benjamin Harrison in Indiana.

But that didn’t last long.

With the D-Day invasion looming and the Allies in need of servicemen, he figures, his orders quickly changed. He was then sent to the University of New Hampshire for the Army Specialist Training Program as an Army Engineer Cadet, then to Camp McCoy in Wisconsin. He was then deployed into France just after the D-Day invasion of Normandy as part of the 280th Engineer Combat Battalion, which provided critical support behind the frontline troops. He was armed with a rifle but never fired it in combat, although there were harrowing moments to be sure, he recalls.

With the D-Day invasion looming and the Allies in need of servicemen, he figures, his orders quickly changed. He was then sent to the University of New Hampshire for the Army Specialist Training Program as an Army Engineer Cadet, then to Camp McCoy in Wisconsin. He was then deployed into France just after the D-Day invasion of Normandy as part of the 280th Engineer Combat Battalion, which provided critical support behind the frontline troops. He was armed with a rifle but never fired it in combat, although there were harrowing moments to be sure, he recalls.

Private First Class Moore, a finance clerk typist and then chemical engineer deployed with the 280th Engineer Combat Battalion, saw action in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Germany, participating in three campaigns – the Ardennes, Central Europe and Rhineland. He was part of Gen. George Patton’s 3rd Army at the Battle of the Bulge.

After V-E Day, when the war in Europe was over, Herb was preparing to deploy to Japan. He was off the coast between Cherbourg, France and England (heading for some brief R and R) when he received the news of V-J Day, the war in the Pacific was over, too, and he would soon be sent home.

Herb ultimately was honored for the American, Ardennes and German campaigns, and in 2016 he was honored by the French government with the Legion d’Honneur, the country’s highest honor.

After a successful business career, Herbert joined the City in 1971 and retired with 17 years of City service.

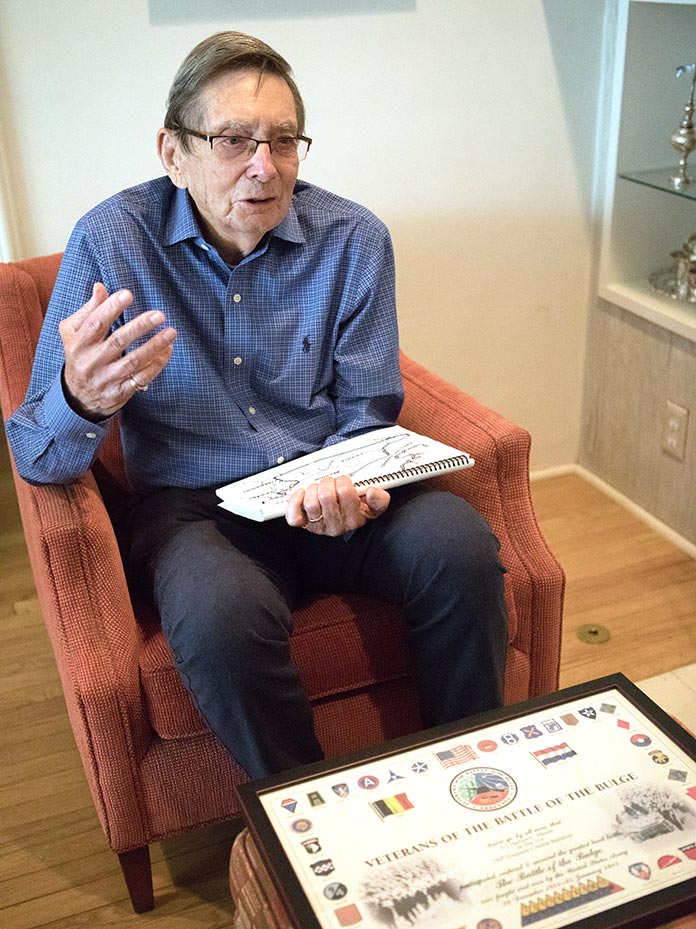

Alive! interviewed Herb late last year at his home in Sherman Oaks, and he had a lot to say about freedom and what America means to him.

This month, we honor Herb and all those who fought in American campaigns to protect freedom.

Behind the Scenes, In the Middle of It All

On Oct. 9, 2018, Club CEO John Hawkins and Alive! editor John Burnes interviewed Herbert Moore, Retired, Controller’s Office, Club Member, and World War II distinguished veteran (private first class) of the Battle of the Bulge.Alive! interviewed Herb, with his wife, Shirley, contributing, at their home in Sherman Oaks. Herb is 95, and he and Shirley have been married for 72 years and have three children: Harvey, Sharon and Robert.

|

Herbert, thank you so much for talking to us today.

Herbert Moore: Thank you for coming.

First let’s talk about your City career. Your title with the City when you retired was?

Fiscal Business Specialist II.

And what department was that?

Controller’s Office. I was in charge of the payroll retirement pension systems.

What was your first job with the City?

I was an accountant in the City Clerk’s Office in the headquarters section. That was 1971.

What did you do between the war and joining the City?

I went back to the University of Michigan and received my AB [bachelor’s degree] and my master’s degree. Then I came out to California with my wife. We were married in 1947. I got my master’s degree in ’49 and because I froze my feet in France [the Battle of the Bulge], I told her that we would never live in a northern climate.

My folks moved out here because I had an aunt and uncle living out here. My dad and his brother then had a big dry-cleaning business during the Depression. My dad came out here more or less to retire. So, he went back in the cleaning business in Burbank. When I came out here, I worked with him and worked part-time for a CPA. Eventually I bought a laundry in Sherman Oaks and built that into cleaning plants in Hollywood and Panorama City, and a couple of laundromats.

What was that called?

Snow White Cleaners on Ventura Boulevard near Sepulveda, and then I bought a couple more. Basically I bought myself a job!

I worked six or seven days a week and took only one vacation during that whole time, and I said “Nuts to this business.” So, I just closed it. My son, Harvey, had been working as a summer meter reader with the DWP while he was going to college, and he talked to somebody there in the personnel section. He said, “Why doesn’t your dad take a civil service test?” I took the civil service test as a buyer and as an accountant and I got a letter saying, “Come in for an interview in the City Clerk’s Office.” So, I had an interview with Mr. Steinberg, and he said, “When can you come to work?” I said “Monday.” This was on Friday. So, he said, “No, you can’t come Monday. You can come Tuesday.” It was Columbus Day. He put me to work right away, and then I took another test. I got called as a buyer at General Services, but I had already received the accounting position. I also had applied to the federal government, too, and I got a call from them to be a bank auditor. But I’d already started accumulating some vacation and some sick time, and we said, “No, we’ll stay where we are.”

How was your City experience?

I loved working for the City. I worked there 17 and a half years. It was a big change. I treated the job as if it were my own business. Sometimes I got bawled out because I was working overtime and didn’t put in for it.

I worked with Hal Danowitz [RLACEI Director and former Alive! travel columnist] in [the predecessor to] ITA. And Rose Hyland in the Controller’s Office.

She’s on the Club Board.

Yes. I was her supervisor in payroll.

That’s great. I’ll tell her you said hi!

Thank you.

The Surprise Soldier

You grew up in Michigan. Is that right?

I grew up in Detroit, until I went to the university and then into the Army.

After Pearl Harbor, in February 1942, I tried to enlist and they wouldn’t take me because my left eye was 20/200, but it was correctable to 20/20. So I joined the ROTC and went along for a while. I couldn’t enlist because of my eye. So, then I was drafted in ’43!

At some point they said “All right. We’ll take you.”

Yes. I wasn’t supposed to be a combatant. I went to finance training – the same basic training as everybody else, but I had some schooling in Army finance, the way to do things, founding and payroll and stuff like that.

Then they sent me to the Army Specialized Training Program, which was training to help develop officers in various fields. Mine was in engineering at the University of New Hampshire.

But – I guess because they had a lot of losses in North Africa and they were planning the invasion, they closed it down and we were sent to the infantry.

Were you expecting to stay in the United States?

No, I didn’t expect that, but I didn’t expect to be in a position to be carrying a rifle and being in the combat unit.

But that changed because of the condition of the war?

It changed very quickly. A lot of us went to the 76th Division outside of Richmond, Va., and one morning, they called me and said they were going to send me to an engineering group. I went to Camp McCoy, Wis., where the 20th Engineers, a combat battalion, was just finished with their basic training going into what they called unit training to teach them what they needed to know for combat.

You ended up in the 280th. What was their role?

To support and do whatever we were told to do. We’d learned to pick up mines, build tank traps, lay mines, build bridges, fix roads, and various things. We dealt a lot with explosives. But we built things, and tore things down. We never had to blow up a bridge, but we were trained to. We didn’t have any heavy equipment. All the heavy equipment had to be attached to us.

We weren’t part of a division. We were under command of an engineering leader. They told us where to go.

So, you were a combat engineer?

I was a combat engineer.

I think the word “engineer,” the way it’s used in the Army, can be misleading to civilians, because we think it’s just paperwork and pencils.

No, no! [laughs] It’s more than that. We went out with a rifle and everything. We did a lot of our work at night. You just stacked your rifle, and if you had to use it, you used it.

What was your reality most of the time?

Our reality most of the time was fixing roads so the trucks could use them to transport. When we got to the mountains, we had to help clear the roads of ice because the tanks were slipping off the mountain down into the gullies.

To Europe

To Europe

So, how did you get to Europe?

By boat. We landed in England for additional training, in Swansea, Wales. We ended up in Glastonbury, where they have the music festivals. So, our battalion was in the city of Glastonbury, and we had all kinds of training – we had training on how to look for booby traps going into buildings. When the soldiers would take cigarette breaks, we would booby-trap the room. We meant nothing dangerous, but just wanted to teach them that whenever you go someplace, you keep your eyes open and you look for booby traps.

Back at Camp McCoy, we trained with dynamite. We didn’t have C4 that they use today. We used dynamite and to make a tank trap, to blow a large space so the tanks couldn’t cross it. If they tried crossing, the front end would go down and they couldn’t get out. One time in training, the lieutenant and I set out dynamite to be detonated by electricity. We came back with the wires, he pulled the plunger and nothing happened. We waited and waited and nothing happened. So, we went back out to reset to see what was going on, and as we were walking away, the whole thing went, knocking us down. Fortunately we didn’t get hurt. We’d ride in trucks with cases of dynamite sitting on them with the igniters in a box. If one went off, everything would go up, because dynamite was very unstable.

Wow. So, after England?

After training in England, we crossed the channel and our company landed in Rouen. We sailed up the Seine.

So, you bypassed Normandy?

We bypassed Normandy. We entered France later in 1944, right after Thanksgiving.

Were you scared when you came in?

No, except the boat pilot who took us up there got stuck on a sandbar, and we somehow managed to clear it! It was an Army boat with a French pilot.

Once you were in Rouen, how did you travel to the front?

Convoys. We always were by Line Company. The 280th split up into three line companies and Headquarters Company. Each company had three platoons and headquarters platoon. I was actually in Company C at the time in the company headquarters. I froze my feet. It was the coldest winter in 25 years. We had no winter clothing at all except our overcoats and our winter uniforms. We had no wool socks. The Army had what they called shoe packs that time, which were waterproof and insulated for the cold. We didn’t get those until the war was almost over, and then we had to give them back.

At that point we were dressed almost like World War I soldiers. I had to write home to my mother for wool socks and a scarf.

When did it start getting cold?

As soon as we landed in France. We slept in the apple orchards, and some of us would take tarpaulins off the trucks and use them under our sleeping bags, but they were not real sleeping bags. You slept with all your clothes on. And it got so cold, I was standing next to a fire and I got blisters on my feet. I couldn’t even feel them. I didn’t realize I had blisters until I took my pants off.

Into Battle

Okay, so you’re convoying from Rouen toward the front.

So we go to a place in France, just before Luxembourg, where we start getting into doing our work. That was Longuyon. We got orders to fix roads or build a bridge or whatever.

Noncombatant actions.

Up to this point. Then we entered the war.

Describe what you were seeing as you entered into Luxembourg. Did you see troops returning, injured from the front?

Oh yes. I saw transports going back past us. Lots of trucks. You didn’t know if your MPs were real or not because the Germans landed paratroopers behind our lines who spoke perfect English and were dressed in American uniforms.

Really.

And they would switch the road signs or they would come in and sabotage the trucks at night. So you had to be careful who you were dealing with. All the way from France we were worried about them sabotaging our trucks. You had to put guards out on the trucks at night.

All the signs on the trucks were painted out. Ordinarily on the bumpers they had the designations, but all those were painted out so nobody would know our movements whenever the enemy saw that we had moved.

After the Battle of the Bulge, we had to move up north and had to make sure everything was painted over. We were transferring from the Third Army to the Ninth Army – Bradley’s outfit. One time in the afternoon, our convoy was stopped by the side of the road and officers who happened to be in Eisenhower’s convoy saw us and stopped. They asked us, “What unit is this, soldier?” We said, “We’re not allowed to tell you, sir.”

And that was Eisenhower’s own team.

Yes. So they went and got the tank commander. He told him, “We could not indicate where we were.” We didn’t know who they were. Just because they had an American car – vehicles and uniforms didn’t mean a thing.

The Battle of the Bulge

Okay so then you’re right there at the Battle of the Bulge in support.

That was the sixth of December 1944 to 25 January 1945.

Did your unit ever have to get involved with fighting?

We did not get involved with fighting. We were support at the time.

Did you see a lot of the aftermath?

Oh yes. We saw a lot of the destruction.

Was that the first time you’d seen that kind of destruction?

Absolutely.

How would you describe it?

Blown-out roads. Bridges torn down. Towns in ruin. There were still civilians around, but not too many. We tried to find a place to sleep inside a building of some sort, or a schoolhouse, some place where it had some heat. I was out on patrol one night and came back, and I had one can of rations. I got back about nine o’clock and I put it on top of a stove. I hadn’t punched a hole in it, and it exploded. That with my supper.

More Americans died in the Battle of the Bulge than in Vietnam.

Yes. It was very bloody. We were lucky. Our unit had a few casualties. I remember one – we were picking up enemy mines and putting them in a truck to unload them someplace. A truck driver, who was supposed to go home – he was 35 with a family, and they were discharging older servicemen – well, he backed his truck up and ran over a mine.

His name was Corporal Duncan.

Were you laying mines as well as defusing them?

No, no, we were picking them up – enemy mines. I was out on mine detail for a while.

How did you look for them?

Metal detectors, with an earphone and a dial, too. You listened – you swept back and forth, and you had a guy in back of you with a bayonet. When you found the mine, he went around you carefully and ran tape on a path to mark that it was clear. There were places where the road was narrow, and you couldn’t get off the road – if you got off the road there were mines on both sides.

So I was clearing this minefield and he went around in back of me, and he took his bayonet to look for mines, to determine whether it was a mine or a fake one. When you found a mine you had to make sure there was no anti-personnel mine on top of the mine for trip wires. Then you dug it out of the ground and put it off to the side. Another detail came later to pick them up.

One day of that can drive you nuts.

That’s nerve-wracking.

If I made a misstep we would both go.

Geez. Did you find any mines?

Yes, sure.

Did you have to defuse them?

Yes. That wasn’t a hard job once you found the mine. That’s easy. That’s the fun. Finding it was hard.

How many days were you on that duty?

About five. That was enough. Infantry would go by us and say, “I wouldn’t have that job for anything.” It was frightening. It was tough.

Were there certain people who were better at finding mines than others?

No. We didn’t lose anybody finding mines.

In all of your time, what was the most harrowing moment that set you back a little?

One of the toughest things was later on after the Bulge. Our company was supposed to take troops across the Ruhr River in wooden boats with outboard motors on them. So we went back to the Meuse River, which was behind our lines, to practice. I had to practice motor starts – outboard motors don’t always start the first time you pull.

And, we were supposed to cross silently.

With an outboard motor?

With an outboard motor taking combat troops, infantry troops, across the river. Maybe 10 soldiers and a guy running the motor.

And we get strafed by an American plane.

On the Meuse River?

Right. The back lines – behind our lines – were supposed to be peaceful. Well, we got strafed by an American plane.

Our trucks had 50-caliber machine guns on a track above the cab with a gunner. Everybody started firing at the plane and the gunner’s got to fight them off with the 50-caliber machine guns. We had given the correct signal that we were Americans, but he strafed us anyway. He could’ve been a German flying that plane, for all we knew. Our captain got yelled at because it was an American plane. But he gave the correct signal. Our lieutenant told them, “We have to protect ourselves, regardless.” Friendly fire happens all the time.

We went to sleep that night, expecting to get up about four o’clock in the morning, while it was dark, to take the infantry across the Ruhr River into Germany. So we got wakened about three o’clock. The Germans blew the dam, so we could not cross the river that way.

We never went on that mission. And I thank God that I didn’t have to go because casualties on something like that would have been very high.

But if you had to …

Well, I’d fight anyway. Of course I’d go. But the enemy was on the other side of the river and we had no protection. We weren’t in a landing ship like they used to come on the beaches. It was just wooden boats with outboard motors. I thank God I didn’t have to.

How did you get over the river eventually then?

We built a bridge across it.

Building bridges was one of the things your outfit did.

Yes. Eisenhower was at that crossing, and some British generals were there, too. The British and Canadians were to our left. We were right at the edge of our sector.

Is that bridge still there?

No, no. We built another bridge across the Rhine River that was there for many years, but it’s not there anymore, either. It was a Floating Bailey Bridge, for tanks. It floated on pontoons. The river was too wide for any other kind of bridge.

How many bridges do you remember building?

Three bridges. The bridges were designed during World War I. They were called Bailey Bridges by the British Army. The parts were like a Tinker Toy kind of thing. You created a place where it was going to start and a place where it was going to end and it came off the truck in pieces. We had to put all those pieces together and then put a floor and put wood across the bottom so trucks or tanks could pass over.

Before we leave the Bulge, where were you during that siege?

We were in Namur.

Were you in Bastogne?

We were doing work all through the area, until the Battle ended.

Have you seen Band of Brothers? They focus on Bastogne for a while.

Some of it.

Were Namur and Bastogne like that?

Part of it was German cruelty. There was a massacre in Normandy where they captured American troops and just shot and killed them. They didn’t even take them back to a POW camp. They just shot them in the field, just massacred maybe a hundred some-odd soldiers. So after that, any of the American troops who captured Germans didn’t want to take them back. But the idea was if you caught an enemy soldier you tried to get intelligence from them. It was a bloody and a dirty war at that point.

Did you have to deal with German soldiers directly?

I didn’t, but I saw them when they were taken prisoner. It was just a good thing that we were able to stop them. Otherwise, who knows?

Were there civilians?

There were no civilians. No civilians at all. It was a big industrial area with coal mines between the Ruhr River and the Rhine River

Were they evacuated or were they killed?

I have no idea. They must’ve been evacuated or left on their own.

How did you feel about finally getting through the Bulge?

Well it was just another job – a big job though.

Into Germany

Okay, so you crossed the Rhine River into Germany.

Somewhere near Essen.

That had to be a big moment.

Yes. But before everybody crossed we had to prepare. There’s a forest there. We brought in big cranes and Navy landing ships. We made platforms for the cranes because they could sink into the ground. And the Army brought in a lot of tanks and field artillery. Before they crossed the Rhine River, they lined everything up wheel to wheel and started a huge barrage over the river because the Germans were dug in on the other side. This huge barrage went on for three or four hours. The Germans were coming out of there trenches, surrendering. We were able to move a lot of troops over to the other side.

What were you armed with? Just a rifle?

We had rifles. M1s. Not very accurate.

How was it to cross the river?

Well, after we crossed, we got hung up by the Germans; their tactics were different at that point. No matter where we crossed the Rhine River, there was a bunch of Germans there. Instead of trying to fight our way through, we’d surround them and take a different way through. Or we would dive-bomb them. All we had to do was make sure they didn’t get out of that trap, then we’d move on to the next trap. We were hop-skipping.

What were you doing when the dive-bombing was going on?

Very little. Just making sure the roads were good.

How long did it take you to build the bridge over the Rhine?

That was about a two-day job.

Wow. How many men?

Well, with the men in the water, we had maybe 25.

When you got into Germany past that first resistance at the river, did it get easier? Did you see that they were losing the war?

Yes. It got a lot easier after we crossed the Rhine.

And you moved a lot faster.

The Army moved faster. We were stuck there, and they were miles ahead. We held back, but the main thrust was going forward. Their goal was to keep going. Keep going, keep going, keep going.

All the supplies and everything had to have good roads so they could move fast. So that’s what we took care of.

On to Victory

Where were you when the Allies declared victory in Europe?

We had moved on to the end. When Germans gave up, we were actually in a town, Mönchengladbach [near Düsseldorf].

What was the mood?

It was great. I mean we expected it, to a point. We knew that they were in bad shape because they fought hard, but they didn’t have petroleum. In Romania there were oil wells that our bombers were hitting and hitting. They had no oil. They had no petroleum. They had no way of moving – they were moving stuff by horses, by wagons.

There was a day when we went through a city and everybody was waving white flags. But we had to back out. There were too many Germans there shooting at us from the street corners. The same people who were waving white flags had guns and rifles and were shooting at the Allies as we were coming. So we backed out.

Were you ever directly shot at?

No. Fortunately.

Did you get to Berlin? Were you ever in Berlin?

No.

Have you been any time since, in peacetime?

No. I would not go back to Germany. Other people [from the unit] have gone. [He and his wife, Shirley] have never taken a trip in Germany or cruised on the Rhine. The closest we got was when we were going to Switzerland and France, there’s a place that, to get to Basel, we had to cross into Germany and then into Switzerland. That’s the only time we’ve been back to Germany.

And by design you don’t want to go.

By design I do not want to go. My mother lost a lot of her family in Poland and Germany.

My uncles and my mother somehow got a cousin out of Dachau. He joined the American Army. He became an infantryman and died at Normandy.

In the D-Day Invasion?

Yes.

And I had another cousin in France who had two young girls who was given over by the occupied government in Paris, France, to the Germans, and she died in a concentration camp. Her two girls, who were American citizens, were saved by Catholic nuns. My uncles and my mother were able to get them over to the United States after the war was over.

Was your mother from Poland?

My mother and dad were both from Poland, but my mother came in 1921 after World War I. My dad and his family came in 1912.

Your family suffered dearly during the Holocaust.

Yes. I have relatives in France and in Argentina from my father’s side. But there were only a couple saved from my mother’s side.

Did you know that at the time when you served in the Army? Did you know that there were camps?

Oh, I had an idea there were camps, yes. That was not publicized. The U.S. did not attempt to bomb the railroads [that transported the victims] into the camps. The State Department wouldn’t allow the railroads to the camps to be bombed. The State Department was very anti-Semitic, if I can use this word.

It’s a very sad story.

There was a shipload of refugees that arrived at the U.S. that they turned back. They ended up in Cuba, or they ended up back in Europe. Or they went to South America. They didn’t let many refugees into this country.

We’re sorry for your loss, Herb. What did you know about the Pacific Theater and what was going on there?

Very little. The Stars and Stripes [newspaper] was giving us the news in Europe. After the war in Europe was over, we went back to Cherbourg, and we were told we were headed to Japan through the Panama Canal and not back to the United States … to not have any rest or relaxation in the United States. Well, when Japan gave up, that was the greatest day in our lives. The threat was over. The Japanese fought to the death. In fact, even after they surrendered, they were still finding Japanese soldiers in caves in the Pacific islands. They didn’t know the war was over.

What did you think of Patton?

He believed in what we call K bars. He didn’t believe in heating rations or anything. They were power bars, and we had a lot of them. You ate power bars instead of having a meal.

Did your unit look up to him like MacArthur in the Pacific?

No, generally he was leading the troops. He was directing that part of the war. But what you heard about him was that he’d go in the hospitals and denigrate guys who were wounded, that they weren’t back and fighting again.

Patton would do that?

So we heard.

He was tough.

Yes! But he knew his business. He knew tank warfare.

So, after the end of the war in Germany, where did you go?

To Cherbourg. They were getting us ready to go to the Pacific.

Were you in Cherbourg when you got the news that Japan had surrendered, and that you were going home?

Well, I was on a boat going from Cherbourg to London for some R and R, before heading to Japan.

That must have been a happy boat.

Yes. I went to London and saw all the damage from the German air raids, and then to Edinburgh for the R and R.

I wasn’t going home yet. At that point, I transferred to headquarters, Channel Base in Brussels. I spent the time between the end of the war and the time I got back to America in Brussels. We were supposed to go to live in a big Army barracks there that had 20-foot ceilings and was cold, and so that was no fun. So we did a bit of black-marketing here and there, and found a place to sleep, because at that point I had a nine-to-four job again. As long as I was there in the morning in the finance section and I finished at night, they didn’t care what I did, except to go back to the barracks to get VD training. You had to attend a lecture and films every so often in the Army. The only reason to go back there to the Barracks was for that, because you had to have that stamped. Otherwise I found ways of living and eating without going back there.

Got it. So you shifted back to doing financial work.

Yes. They needed people in the finance department. It took me longer to get home, because I was declared essential in the finance department! [He laughs.] I stayed there as long as they wanted me, and then we went to Amsterdam and slept in tents. We wouldn’t get up for breakfast unless they had fresh eggs, because most of the time they served dehydrated eggs.

I went home through the port of Amsterdam.

Home at Last

Where did you reenter the United States? New York?

Yes.

Do you remember when you saw the Statue of Liberty?

Oh, yes.

How did you feel? What was the mood on the ship?

We were home, finally home.

Did you come back on a commercial liner?

Oh, no. Troop Transport.

It must’ve been amazing that time when you came in.

It was. But the only problem was when we got off the boat, the German POWs were there, getting on the same boat to go back.

To go back to Germany?

To go back home from the POWs camps here in the United States. They shipped a lot of Germans to the United States. They got paid so much money per day. After the war, they went back with loot from the PXs and stuff like that.

Really? What did they have?

They had radios and stuff. I know our POWs weren’t treated that way.

Of course.

The thing that bothered me most, when we got off the boat, they were talking about war with Russia. “Oh,” they told us, “you’re going to turn around soon and go back and fight Russia.”

Wow, that soon.

The mood in this country turned against Communism. When I was growing up, we had Socialists and Communists on the ballot. Nobody thought anything of it. The father of a friend of mine was on the ballot in Detroit, for the Socialist Party. You had the Republican, Democrat, Socialist and Communist, and you voted the way you wanted to vote. The country turned against the Communists, but that wasn’t until after I got back.

The Russians were supposed to be our allies. They fought on the Eastern Front. They lost a lot of people.

When we were in Germany just after the war was over, we were feeding POWs and people from slave labor camps. Some were Russian, and there was one Russian kid who latched onto our outfit and wanted to work around us. He had been captured by the Germans and sent to a camp in Germany, and after the war Germany’s POWs were actually walking back to the various countries where they came from. I mean, walking. We didn’t like Army pea soup, and we had a lot of that. So the cooks would heat the pea soup and feed these POW guys. They got to the front of the line, got their pea soup, drank it, and got to the back of the line to try to get some more, or get some bread. They had nothing to eat. Anyway, this one Russian kid wanted to come back to France with us and then come to the United States.

But he had latched onto your unit?

Yes.

Back to France

So you’ve been back to France a few times since the war. Most recently you were awarded the Legion d’Honneur.

The French consulate in Los Angeles gave me that medal. The ceremony was at my synagogue in Valley Glen. Three other Veterans received the Legion of Honor medal, too, at that ceremony.

Right, okay.

The people in the consulate were very nice.

How was it to go back?

The first place we stayed was at a bed and breakfast that happened to be owned by an American engineer who married a French woman who’s also an engineer. I wore the [military] cap, and every place we went, we were treated well: in restaurants, on the street and on the tours. It was a fantastic trip, part of it because we were with family. We were treated like that in Paris, too.

Did you go through Paris after you landed first in 1944?

No, but I got to Paris a couple times. One was when I was going from Cherbourg to Brussels [to continue working for the Army in finance after the war], and the other time, a group of us went on a pass from Brussels.

But not back to Germany.

Never.

Of course.

The Meaning of Freedom

What does freedom mean to you?

Freedom means being able to vote. And it doesn’t mean nationalism, which is pulling our country apart. When I think of Hitler, I think of nationalism. I was able to speak German to the local civilians after the war was over, and they said, “He put butter on our table.”

I don’t want to bring politics into it, but nationalism is the enemy of this country. This country is made up of all kinds of immigrants, whether they’re illegal or not. They’re only illegal because we say they’re illegal, because we don’t give them the opportunity to come to live a better life. Those I’ve met and those I know have all worked very hard.

For 25 years I’ve been doing income tax as a volunteer with the AARP. The IRS gave those who are here who can’t get a Social Security card on their own as a way of paying taxes, and they do come in and pay their taxes. There’s a way for them to pay taxes and support this government. The food that we eat on our table is picked mostly by people from Mexico. There wouldn’t be any strawberries on your table from Oxnard if it weren’t for those people, because nobody else would do the picking.

It’s backbreaking labor, and they do it. There was a visa program that allowed them to come and go back legally. They can’t do that anymore.

We had tariff wars in the 1930s. That’s part of why we had our Depression, because of tariff wars.

We live in a global economy. We rebuilt, for example, the steel mills in Japan after we destroyed them, and in Germany. That brought them out of a situation where they couldn’t buy anything; they couldn’t put food on the table. When you raise people’s standard of living, you’re not going to have wars. You keep pushing people down, you’re going to have wars.

Our country hasn’t always welcomed immigration, because each group that gets here wants to put down the next group, but it all works out. The Germans and the Italians and the Irish – they were all looked down at, and it was hard for them to get jobs. But to not be compassionate to people who want a little better life and don’t want to worry about their kids being killed by gangs and things like that isn’t the United States.

Herb, what’s your secret to being so healthy?

Shirley [wife]: Me!

My wife! My genes, too, I guess, because my mother’s father lived to 105 in Europe. And she lived to 101.

My dad lived to 96 and a half.

Herb, thank you most sincerely for this amazing interview, and for your service to our country. We are all in your debt.

You’re welcome.

BEHIND THE SCENES

Club Director of Marketing Summy Lam (foreground) captures (from left) Club CEO John Hawkins with Herb and Shirley Moore in their Sherman Oaks home. |