Alive! photos by Summy Lam and John Burnes,

Alive! photos by Summy Lam and John Burnes,

and courtesy the Bill Lillenberg family

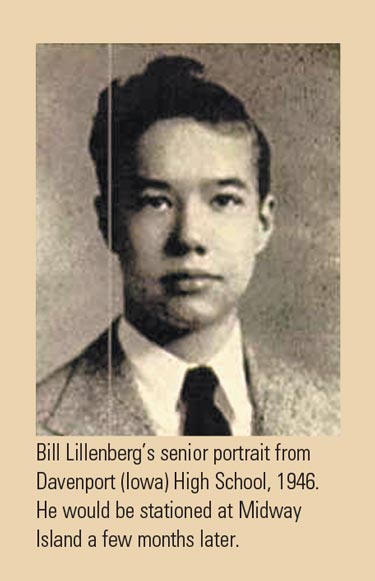

Bill Lillenberg, 91, Retired, Planning, and US Navy veteran, served at Midway Island just after the war, then joined the NSA at the beginning of the intelligence agency. Here’s his story.

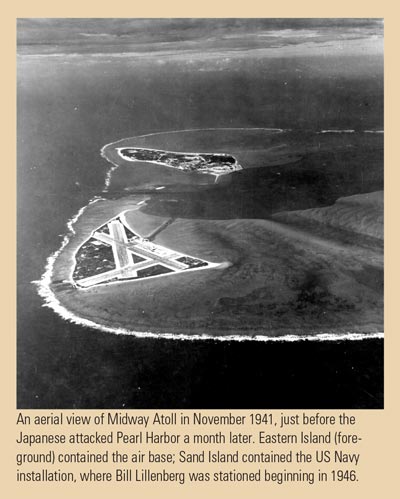

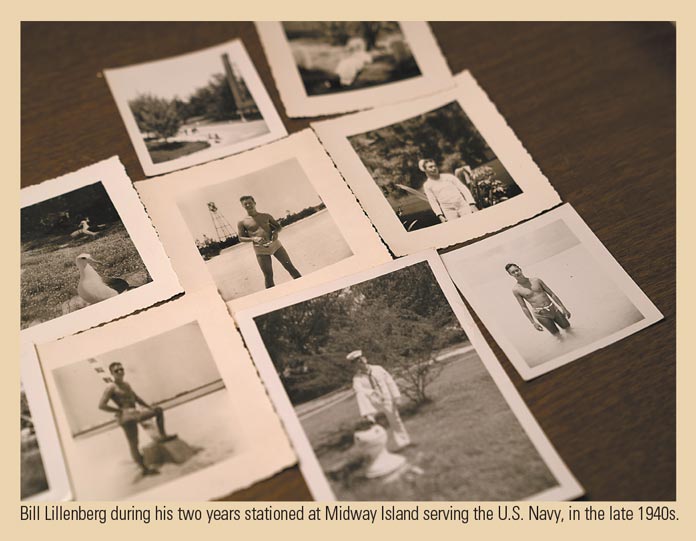

In 1946, Bill Lillenberg went from his high school graduation in Iowa to Navy boot camp and Radioman training in San Diego just a few weeks later. Then he went on to Pearl Harbor and finally Midway Island a few months after that. When he arrived to begin two years in the middle of the Pacific, signs of the critical Battle of Midway four years earlier were still visible, although they were largely cleaned up. He even worked alongside several Navy seamen who actually remembered the battle, and battle debris would wash ashore almost daily.

His military career ended in the early 1950s when, as a Naval reserve Officer, he was recalled by the Navy back to full service during the Korean Conflict. The reason: Bill had developed strong skills managing messages over the radio waves. He was tasked to do just that in a brand-new US intelligence service, the National Security Administration (the NSA). He was part of the very beginning of what is now one of the world’s top intelligence-gathering bureaus.

And that was all before he left for California with his late wife, Mary Alice, and began what would be a more-than-38-year career with City Planning.

He’s lived a full life of service. And now, as part of Alive!’s annual tribute to the servicemen- and –women on Independence Day, we asked Bill to tell us about his service career, and what freedom means to him.

Read his story below.

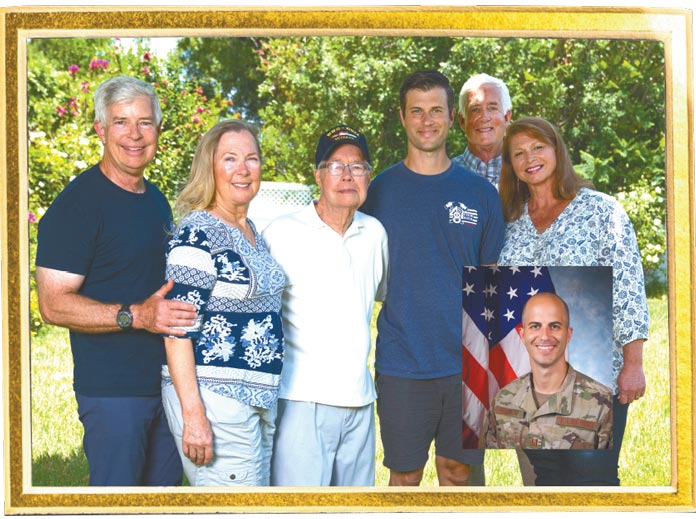

A Family of Service

Bill and (the late) Mary Alice Lillenberg raised a family dedicated to City and national service. Their offspring:

Sons

Eng. Mark Lillenberg,

Retired, Engineer, LAFD (FS 95 at LAX) with 30 years of City service

Eng. Kevin Lillenberg,

Retired, Engineer, LAFD (FS 97 off Mulholland Drive) with 32 years of City service.

Daughter

Det. Amy Lillenberg,

Retired, Detective, LAPD ( West Valley Division/Burglary) with 25 years of City service

Grandsons

Capt. I Joshua Lillenberg,

Active Capt. I, LAFD (FS 48 in San Pedro), 17 years of City service

Capt. Christopher Lillenberg,

dentist in the U.S. Air Force

From Midway to the Capitals

On June 4 – the 78th anniversary of the Battle of Midway during World War II – Club CEO John Hawkins and Alive! editor John Burnes interviewed Bill Lillenberg, Retired, Associate Zoning Administrator, City Planning, 38 years of City service, at his home in Granada Hills. Bill, 91, served in the United States Navy at Midway Island less than a year after the end of the war and, later, was on staff of the National Security Agency (NSA) in Washington, DC, just after the famous intelligence agency was formed. (Hannah Hawkins, John Hawkins’ daughter, 15, is studying World War II in school and contributed to the interview.) Club crew remained safely distanced.

Alive!: Thanks for inviting us into your home today, Bill, and having your family here.

Bill Lillenberg: Sure.

Let’s start with your department. You retired from Planning, is that correct?

City Planning. It was called City Planning then.

Okay. And what was your title when you retired?

Associate Zoning Administrator.

And what did that entail?

I was like a judge who handled land-use matters. People who were developing subdivisions, shopping centers, hospitals, churches came in to apply for permits. If they didn’t meet the zoning code, they would have to file a variance. I was the judge who listened to their application and would write a report saying whether I approved it or disapproved it.

Got it.

I got a lot of liquor stores.

Really?

Yes. You had to be in an industrial zone or a commercial zone. If you had a massage parlor or a liquor store, you always had to file an application for that. And the Police Dept. would always check with me whether there was a high crime in that area.

How long did you work for City Planning?

Thirty-eight-years.

When you came out to LA with your wife, did you go right into City employment or did you do something else?

We came out here and we lived with [wife] Mary Alice’s sister and parents for a few years, and then we got an apartment by ourselves. I was going to Valley College. A lot of veterans were going there at the same time.

So after you were discharged from the Navy, you returned to your home in Davenport, Iowa to attend college at St. Ambrose University.

St. Ambrose. I was at St. Ambrose only one year. Before St. Ambrose I worked for Alcoa, an aluminum mill just north of Davenport. I was foreman there.

Why did you stop going to school in Iowa after only a year?

I had joined the Naval Reserve. I finished one semester at St. Ambrose and I got recalled back into the Navy. The Navy sent me to Washington, DC. And that’s where I met my wife.

Okay we’ll get to DC in a few minutes, for sure. You joined the Navy after graduating from high school in Davenport?

Okay we’ll get to DC in a few minutes, for sure. You joined the Navy after graduating from high school in Davenport?

Yes. I graduated from high school in June 1946 and joined the Navy in July of ’46 at the age of 17.

You were just under the threshold, so they let you in.

That’s right. I went from Davenport on a really long train ride to San Diego for boot camp.

My first tour with the Navy took about three-and-a-half years. Then I got out and was out in the Naval Reserve for about a year before they called me back. When I was out during that year I took all kinds of jobs I could get to make some money so I could go to college.

I had a friend who said, “You should get in the Reserves. You go to a meeting once a week and you get a little extra pay. Don’t worry, they’re not going to call you back!”

But they did.

Yes. I got a nasty letter from the Navy that just said, “Report.” They gave me four days. And that’s when I went to a little base north of Chicago to start training again.

Whey did they call you back?

The Korean War had just started. They called me back to do exactly what I was doing before. They wanted me because I was in Communication.

Right. A Radioman.

Yes. When I got there in Washington, DC, I had to take all these exams about my background. They hooked up a lie detector.

Yes, I imagine.

The guy running the lie detector would go up into a little booth and look down on me to see if I was going to fool around with that lie detector! About five minutes later he’d come back down and he’d look at the machine and say, “Okay, you pass.”

They wanted you because you were a Radioman – you were very good at picking up signals through various communications methods right?

That’s right. Yes.

Did they ask you if wanted to be part of the NSA?

I had no choice. I didn’t want to go to the NSA; I wanted to go back into the Navy. But NSA was just forming [in 1952]. I had to wear an ID tag around my neck showing that I had clearance.

Right.

I was still part of the Navy. The branches were all there.

How long was that second stint in the Navy?

About two years.

Okay. And then you got out, got married, and came west. And then the schooling started.

Yes. I transferred out of Valley College and into UCLA on the GI Bill, where the Navy would pay my expenses and my rent. And then to USC for my Master’s degree.

Okay, thanks for that rundown. We’ll get back to all that.

Sure.

City Career

Let’s go back to your City career for just a minute.

All right, go ahead.

Did you enjoy working for the City?

Oh, Yes. Yes, I liked it a lot. I would have worked longer but 38 years was a long time.

You must have enjoyed what you were doing.

Yes.

Did you train for that at UCLA?

No. After graduating from UCLA, I got a job in Burbank making parts for aircraft. The war was winding down and they weren’t building those airplanes anymore, and they went bankrupt. I told my wife, “I can’t work with these kind of jobs. I want to have something that’s more definite and permanent.” That’s when I started looking for a job in either the City or the County.

I was unemployed and I went down to City Hall and the Personnel Dept. I looked on the bulletin board to see what they had available. City Planning looked like about the only thing I could get into. I couldn’t get into Engineering or Water and Power or Police or Fire. I applied there. They checked my background, took my application and gave me a test.

Right, a Civil Service test.

Yes.

What are your best memories of working for the City? What did you really like about it?

Equal opportunities. You had to work hard and get good ratings. At the end of every year, they’d rate you on how well you did the job. And then they would give you a test if you wanted to move up to the next level. It was very competitive.

Who was your favorite mayor to work for?

Tom Bradley.

He was good?

He was very good.

What made him good?

He was concerned about all the departments. He would tour through the Planning Dept. and see how things were going.

He was a boots on the ground kind of guy.

He was. He was easy to approach. There was another mayor who was a lawyer.

Richard Riordan?

Yes. He owned a restaurant downtown.

He still does.

He would call me down to his office all the time to sit down with people who were having trouble with the Planning Dept. I would sit at this conference table with these developers and answer their questions and tell them what they had to do and what they didn’t have to do. He called me all the time.

As the Associate Zoning Administrator?

Yes. But I was kind of the assistant to the Zoning Administrator. When he would go on vacation or when he was out of town, I would get his phone calls and all his problems. I remember one time I got a phone call and the man said, “I’m the head of security at a City park. We have a helicopter coming in to you with Frank Sinatra.”

Frank Sinatra?

Frank Sinatra!

Of course. He always arrived in a helicopter!

He came in with his two or three assistants. They were having concerts or programs or something next door to the park, which was an outdoor area. After his thing was over, he wanted to come back to the park and get in his helicopter and fly back to his home in Orange County where he was living.

Do you remember what park that was?

The biggest park in the City of Los Angeles, with a big water fountain.

MacArthur Park?

Yes.

He flew his helicopter into MacArthur Park?

Yes.

Your three children all worked for the City. Did you recommend your kids and grandson to join the City?

I told them, “Get a job where you won’t get fired every time the economy went down. I want you to get a job that’s stable and predictable and they treat you right.” And they all went into the Police or the Fire Dept. My daughter went into the Police Dept. and my sons went into the Fire Dept. And my grandson is now a Captain with the Fire Dept., down in the Harbor.

We’ve been doing this version of the Alive! newspaper for 17 years, but we have not come up with a family with that much City Employee experience. Not that I remember. Especially at high levels.

Nobody ever asked me about it before.

To Midway

So you were in high school when World War II ended.

The war was over when I was in radioman school in San Diego.

How did you get from Iowa to San Diego?

By train. In those days nobody flew. If you went on the train you were either a troop, sick, coming out of a hospital, or you were a passenger trying to get out of someplace else. People who flew were the executives or congressmen or the presidents and people like that.

So you went to boot camp in San Diego and then immediately to Radioman school.

Yes, right out of boot camp. They were in the same place, just a half-block away.

Why did you choose the Navy? Or did the Navy choose you?

No. I had family members who were in the Navy and they seemed to like it. The draft was just about over but I didn’t want to go in the Army.

How did you choose to be a Radioman?

As I got through with boot camp, they looked up my high school education and they said, “We’ve got the people we need in two areas, and you can pick the one you want.” I said, “Which ones you got?” They said, “You can be a Hospitalman helping the doctors.” I was no nurse. “Or you can be a Radioman.” I said, “Is a Hospitalman the one who draws blood, and gives you shots in the arm?” They said yes. And I said, “I’ll be a Radioman.”

The Radioman works in a pretty secure environment, right?

Yes, right. You had to work around the clock. I used to work a week of days, a week of evenings and then work a mid-shift. I did that all the time.

You had top clearance.

Yes. the reason we had the clearance is because the messages were coming in and were were reading them before the Captain got them. They want to be sure that we were cleared because the Captain’s going to have to use this for this is his orders from the Pentagon.

It was a pretty big deal.

Yes.

Tell us what a Radioman did. You were at Midway Island, not on a ship. What did you do?

Well, I didn’t do Morse Code very much. It was fading out. Most of the work we got came via Teletype from Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

You would hear those signals on an earpiece?

No. It printed out on a typewriter. We had one unit – if it was important for the Captain, we would pull out that report and make a copy of it and run it across the hall to the Captain. And if we wanted to change frequencies, we would call our office nearby and they would change the frequency for us. We’d change the frequency at nighttime. The signals were stronger at night.

What did you do after Radioman school?

What did you do after Radioman school?

That’s when I went to Midway.

For how long?

Two years. But when I got there it was only supposed to be for one because that’s such a miserable place to be. It’s just a pile of sand on a small island. Then they extended it three more months. I just kept working, and they didn’t say anything about extensions after that. After two years, they said, “You’re going.”

How did you get from San Diego to Midway?

On a Navy ship. It was also carrying cargo.

What was your first impression of going there?

I was disappointed.

Why?

I said, “What kind of a ship is this?” And they said, “Just get on board! You’ll be all right!”

What was your impression of Midway Island? After hearing all the stories about the famous battle that happened there.

It was an island that was mainly sand and there were a lot of gooney birds everywhere. The radio room was underground – it was still recovering from the war, and it was a deep underground vault-type place. You’d walk down some steps and you’d go through these steel doors, and that’s where the radio room was. Next to the radio room was a conference room where the Captain held his meetings when they were under attack. There was a machine where you could turn on the electricity if the power went out.

There were some bunks and a little kitchen across from the radio room where people could stay overnight if they couldn’t get out, when the island was under attack during the war.

You’ve been back since.

I went back there as a civilian with my wife. The Navy had left and it was taken over by the federal government as a park or reserve area. People would come there and go fishing and surfing. We stayed a week.

Yes. Was it different when you went back?

It was all closed down. I stayed in an Officer’s quarters and I was a civilian at that point, so that was kind of nice for me.

When you went there the first time, right after the war, was there any debris or destruction that had been cleaned up, or still in existence? Could you see any damage from the Battle of Midway?

No. The damage was all cleaned out. They still had a lot of food leftovers, though. Our food was all in cans.

C-Rations?

C-Rations. We never had any milk and we had coffee. But we never got anything fresh.

Was anyone still stationed on the island who was there during the war? Was anybody still there?

A few. They were all the second-class and the first-class Petty Officers. They were getting ready to leave. They wanted to go back home because the war was over. I was taking their place.

How did they treat you?

Like hell. Like, “Get out of my way, you punk.”

I lived in a barracks on the second floor, and all the Radiomen were in that particular area. The Seabees who built everything were transferred to Kwajalein [Atoll, in the Marshal Islands] later because they didn’t need them anymore on Midway.

Did you go to any of the other islands near Midway Island?

Yes, I did. The Captain or his assistant would make trips up and down to the other adjoining islands to see if everything was under control. I went on that trip twice. I went on as a Radioman. We usually would take a Nurse with us and an Engineer to run the engine. And we would take food to last us for our lunch before we came back. It was quite a trip getting out there and along these little islands. You could see all kinds of debris from ships that had been sunk and lifeboats that had washed up.

During the war, Marines were stationed up on the hills on top of these islands. We could see where they had been.

As a Radioman, were you handling almost entirely U.S. communications or were you also intercepting foreign communications?

Just the U.S. communications. It was all stuff that came from Hawaii to the Captain.

Was it coded in any way?

No. It was plain letter. He would come in after about 5 p.m. when everybody else had left. He’d come by and look at the Teletype and look at all the messages that came in. One day. the Chief Petty Officer came by and said, “The Captain wants you to raise your elbow next time you shave because your sideburns are getting too long.” That’s a true story!

Oh, that’s funny.

He wouldn’t talk to me personally. The Captains never talked to the people. It’s always down the line.

When you settled in at Midway, were you thinking, “I hit the jackpot. This is awesome. I love this warm weather and the beach?”

No. I said, “What did I do to get this place?” I thought I was going to go aboard ship someplace.

But then after Midway, you did.

But then after Midway, you did.

Right. After being stationed on Midway for two years, I went home for about three weeks, and then I had to get back to San Diego.

You were being reassigned to a ship.

Yes. I was a Radioman on a passenger ship, the AP-133 [The USS General Ernst, decommissioned by the Navy in 1946 and transferred to the US Army]. Most of the passengers were enlisted men, but sometimes it would take Officers and their families to Hawaii and drop them off. Or it would take Marines towards China or other places.

And how long were you on that?

About 18 months.

Pretty much the rest of your enlistment.

Yes. Most of the time we went from Midway back to Pearl Harbor. I went to Guam once. I picked up a division of Marines and brought them back to San Diego, and then they went up to Camp Lejeune by bus.

Were you glad you were on a ship and not on Midway?

One thing I liked about the ship was that we had a chance to see different places. I went to San Diego and then up to San Francisco, and I could get off there and go through the Harbor, that big harbor they have up there in San Francisco.

Do you have fond memories both of being on Midway and on the troop ship?

Not Midway but on board the ship – I kind of enjoyed that. I like traveling.

And we didn’t have just sailors. We had Marines and Officers and their children and wives when the War was over. And on board the ship we started getting fresh food. They could pull into port and get some milk. Everything had to come to Midway by airplane and or ship.

Did anything happen to you on Midway that you would consider unusual, or scary, or funny, even?

Each department had to provide one person to get rid of the trash that accumulated on Midway, and they put it on a flat barge. A tugboat would take them out. We would get on that flat barge and it would pull us out maybe about two miles from Midway. Our Chief Petty Officer and we would push this trash off, and it would sink down into the ocean. It was all things that they couldn’t burn or get rid of on the island.

Like metal and debris?

Yes. That’s the way they got rid of it.

Anything scary?

One time we got a report that there was an earthquake up off of Alaska and it said these waves were coming down towards Midway and we had two hours to take precautions because it was going to wash right over the island. The whole island went to general quarters. I went to the radio room and we were all standing there waiting for that storm and that wave to hit the island, and it missed us.

Wow.

We found out later that it turned and went toward Hawaii. It didn’t hit us after all.

On to the Reserves, And Intelligence Work

So then you you finished your enlistment, were discharged, and you’re finished with your Navy service. You go back to Iowa, back home. And you work for Alcoa.

Yes. After Alcoa, I had a couple other little jobs waiting for the semester to start at St. Ambrose.

You got into the Naval Reserve.

Right. When I was working there, a friend of mine in the Navy said, “Let’s join the Navy Reserve. If we join the Navy Reserve, we can go to meetings one night a week and get some money for it.” I said, “What do we do with the Navy Reserve?” Oh, it’s kind of communication work, too, he said. “But it’s security work. They might have to check your background.” I was clean; there was nothing to see. And so we joined, and I did that only for maybe about six weeks and then the Korean War broke out. And it took about five days to get that letter in the mail – “Report to the base north of Chicago.” It was called Great Lakes.

We called it Great Mistakes.

Great Mistakes!

So because you’re in the Naval Reserve it made you eligible for the Navy to call you back?

Yes. I should have joined the Foreign Legion or something!

Except you eventually met your wife through that.

Right. Then they moved me to Arlington, Va. Quarters K. Just south of DC, near the cemetery. Just a block away from where all the veterans are buried.

In front of that was Fort Myer, a ceremonial place where they had horses. If there was anything going on down at the White House they would be part of the parade that would carry the horses and people in the parade. They would guard the president.

They called you back because you had extensive experience as a Radioman, right?

Yes.

But that job had grown. You weren’t just receiving messages, you were in I guess the intelligence service now.

Yes.

My dad was in at the same time, during the Korean War. He was sent to Germany with the Army, and he was in the Counterintelligence Corps.

The stuff that he got was probably sent to where I was in DC That was the center of gathering all the information from Europe, the foreign broadcasts, past and present. We would get messages from Russian planes that were flying over and photographing the American Navy.

My mother said, “Billy, where you working now? The FBI is coming around asking all kinds of questions about you! And not only me, but the neighbors. They want to know what kind of person you are – do you drink a lot, are you trustworthy?” And I said, “Mom, don’t worry about it. I’ll clear that.”

That’s when you were a part of the NSA. It’s what your training led you to.

When I got there, when I was waiting for a clearance, I worked in the dental office. Here we had a medical and a dental office next to this Navy base. It was guarded by Marines, and I said, “When am I going to get my clearance?” And he said, “Well, they’re working on it and I’ll let you know when you get it.” Turns out the [superior] was holding up my clearance because he was getting first-class service getting his teeth cleaned and examined. They were shorthanded of people and I was taking the appointments and helping the dentist doing extractions, and I was learning all kinds of things. The dentist asked me if I wanted to stay on. And I said, “Well, I’m a Radioman. I can’t do any dental work here.” I pushed the issue with the JG, and two days later I got my order that said to report [to the Naval service within the NSA].

That’s all it took.

Leave and go.

So what did you do at Quarters K?

It was a mixture – everybody who wasn’t married and were lower staff were stationed there. The women were up the street and the men were down the street. In the middle were the kitchen and the dining area where we ate. I would come out of my barracks and get on the bus, and it would take me to work.

I went to this Army base post that was turned into the NSA to use to create their organization. We would take messages from around the world that came in on Teletype, and we just rolled all the tapes up and send them out to the different areas that would monitor those areas. These people were trained to break down foreign broadcasts and read the foreign messages.

What did you tell people you were doing? That you were working for the NSA?

I just said I’m still in the Navy.

When I was doing Radioman work, the National Security Agency referred me to the CIA, and I had two interviews with them. They wanted me to go to Italy. “We could use you there,” they said. And I said, “No, I’m getting married about this time. I don’t want to leave the country.”

How did you meet Mary Alice?

How did you meet Mary Alice?

On a bus going to work. A shuttle bus would take us up to this Army post that was taken over by NSA. She worked across the hall and she worked for I think a Navy Admiral, and she was kind of the secretary.

The Yeoman.

That’s exactly correct. I worked across the hall in the Communication area. She couldn’t come into my area because she wasn’t cleared.

What was that first meeting like?

She wouldn’t talk to me. She thought I was too young for her, until a friend of hers told her I was a year older than she was. And then we became good friends. All the WAVES (US Naval Women’s Reserve) were looking for husbands. A lot of WACS [Women’s Army Corps], too.

It probably gave her confidence that you had been through all that security.

She didn’t care. She didn’t ask me about my background.

She didn’t?

She didn’t care whether I saluted the flag or not. She just wanted a husband who was going to be stable so she could get married!

And she got one.

Yes. She did.

How long did you stay with the NSA after you got married?

About six months. In the WAVES, they said if you get married, you could get out within six months. So we got married and then I worked at the NSA as a civilian until she got all out of the Navy. Then we put everything that we had in the car and drove to California where she was from.

How did you feel about the job you were doing?

I was treated fine but the job was difficult. They kept telling us, “You keep your mouth shut. You don’t talk about this job.” We had a couple of guys who were new and they were on minesweepers or destroyers or something. After work we were sitting in the bar and a couple of those guys came in and said, “Hi, how you doing? What’s your name? Do you work around here? What work do you do?” They were gone the next day.

They could have been spies.

Yes. It happened to me several times.

We would get off on the evening shift about 11 and go in a car. One of the guys had a car. And we’d drive a car to a small restaurant nearby and we’d order a pitcher of beer. We’d all sit around this table. And we’d go up to this counter and order our sandwich. While I’m waiting for my order to come, this guy would walk in – one guy would stand by the door and one guy walked to me and said, “Hello, there. Are you working around here somewhere? I think I know you from back home.”

Yes. “You look familiar.”

And I said, “I don’t know you and you don’t know me and I’m getting my sandwich and I’m leaving.”

Good for you.

They warned us about that. They said, “You don’t talk about what you’re doing here.”

Would you consider yourself a code breaker?

That was somebody else’s job. Towards the end I was. I didn’t set out to make a career of it, but the code breakers were down the hall in another area.

So your job mostly was to receive the signals and prepare them for other people.

Yes. And send them on down to them.

What I did was – you would look at the time of day and you put the certain type of disk into this machine that would break the code. I would run that machine and it would come out in English and then I could print it.

So they were already using computers to break codes and things?

Yes … well, I don’t know if they were or not because I didn’t work in that area, but I know that we had a Teletype.

We were doing that right after World War II, and it just kept going on. There were all kinds of military conflicts after World War II. If it wasn’t for Russia, it was for the Middle East or China. It was always some country.

You were at the dawn of the Cold War, which was crazy.

Yes.

And the nuclear age. Did you ever have any experience or run-in with the nuclear testing that was going on in the South Pacific?

No. They came in after I left.

What were your thoughts about MacArthur?

MacArthur was kind of a stubborn, and not a very friendly person. I never met him. He was in the Army. I was in the Navy. I didn’t know him personally. I felt that he did a good job, but he didn’t have the personality that a lot of people should have in that kind of high rank.

If you didn’t know him you probably liked him because there was a lot of publicity about him. And his father was a very important man. They always showed him with his wife and they were in the Philippines and things were going just going great. But [in reality] he was a hell of a person to work for.

Okay. Then you moved out to California, went back to school, started a family and eventually started working for the City. Where did you live?

North Hollywood, Pomona for a while and … you know, different places.

But back at the NSA now, which has grown into just an enormous agency – is that not something that you wanted to do the rest of your life?

I would have stayed in, but they didn’t want me to stay in the country. They wanted me to go to foreign stations in Europe or Africa. When I got near graduation time at UCLA, I got interviewed a couple more times, and they asked me if I wanted to come back because I had the experience a lot of these kids coming out of the school didn’t have. They sent me letters and they interviewed me a couple of times. And I said, “No, I don’t think I want to go back anymore.”

The Meaning of Freedom

The Meaning of Freedom

Do you consider yourself a patriotic person?

Very. I put the flag up every Fourth of July and Veteran’s Day.

Are you proud of your service?

Yes, I am. I never got in the brig!

What does freedom mean to you?

A right to do what I please within the laws of the country. To raise my family the way I want to have them. And to serve my country if necessary.

Would you recommend serving our country to young people?

If you want to go in for a temporary time just to kind of get away from home and see what it’s like, do it because it’s a good experience. But don’t go into the Army or don’t go into the Marines. Go into the Navy or the Air Force.

What other advice would you give?

Get married. Have children. Teach the children the right way to live. Get a good education because if you don’t have a good education you can’t get a job.

Yes.

I mean a job that lasts. If you’re going to have children you’ve got to be able to support them.

I understand you have some favorite sayings – “Don’t leave that door open. What, are you trying to cool off the neighborhood?” “Life is what you make it.” “No pain, no gain.” “Work hard.”

Yes they sound familiar!

Bill, thank you very much for your service to our country, and thanks for sharing your stories with us.

You’re welcome.

BEHIND THE SCENES

Summy Lam, Club Director of Marketing, photographs Bill Lillenberg, Retired, City Planning, in the backyard of his house in Granada Hills. |