Photos by Summy Lam, Club Director of Marketing,

and Alive! editor John Burnes

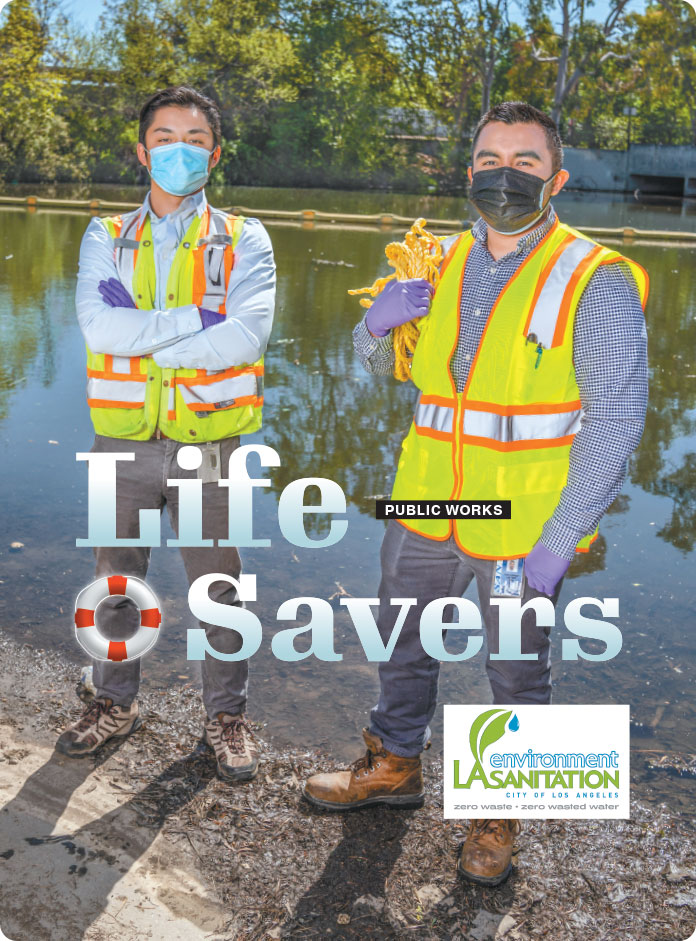

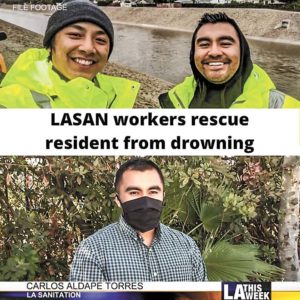

While monitoring pollutants in the water, two LA Sanitation and Environment employees save a man from drowning.

Carlos Aldape and Johnathon Truong went to work Jan. 25, checking on automated equipment that monitors the City’s watershed for pollutants at the Wilmington Drain. When they got there, they heard something they didn’t expect – a man screaming for help. He was in the drain pool and drowning. They called 9-1-1 and then rescued him.

-

Johnathon Truong’s and Carlos Aldape’s heroic feat was featured on ITA’s Channel 35.

Saving a man’s life might not be a part of what they do every day – Carlos is a Lab Tech and Johnathon is a Chemist. But it fits right into their mission, for the Watershed Protection Division monitors our City’s water runoff to make sure it’s within regulations for healthy living. For that one day, though, their mission became more acute and focused on keeping this one Angeleno safe.

In this feature, read all about the Watershed Protection Division’s mission, that life-saving day, and what it means to have a duty to save lives and pay it forward. Congratulations to Carlos and Johnathon for their good deed, and for their lessons for all of us.

Sanitation’s Watershed Protection Division

The two lifesavers, Carlos Aldape and Johnathon Truong, work for LA Sanitation and Environment’s Watershed Protection Division. They were checking water quality monitoring equipment at the Wilmington Drain when they discovered a drowning man, and saved his life.

LASAN’s mission is to protect public health and the environment. Watershed Protection Division protects the beneficial uses of receiving waters while complying with all flood control and pollution abatement mandates. The program employs a multi-pronged approach to ensure the City of Los Angeles is in compliance with regulations and reduce the amount of pollution flowing into and through regional waterways.

Its different focuses:

Low-Impact Development is a leading stormwater management strategy that seeks to mitigate the impacts of runoff and stormwater pollution as close to its source as possible.

Low-Impact Development is a leading stormwater management strategy that seeks to mitigate the impacts of runoff and stormwater pollution as close to its source as possible.- Green Infrastructure captures, cleans and infiltrates stormwater through the design of paved areas using permeable materials and drought-tolerant plants. Converting the City’s paved areas from gray to green will reap multiple benefits.

- Proposition O authorizes the City to fund projects (up to $500 million) that prevent and remove pollutants from the City’s regional waterways and ocean, consequently protecting public safety and meeting Federal Clean Water Act regulations.

- The Enhanced Watershed Protection Management Program manages the collaboration of municipalities, non-governmental organizations and community members to develop and implement plans for LA’s five watersheds.

- Environmental Compliance protects public health and safety and the environment through effective education, prevention, emergency response, criminal investigations and enforcement of federal, state and local laws.

- In 2018, Los Angeles County voters approved Measure W, a special parcel tax funding the Safe, Clean Water Program (SCWP). This program provides local, dedicated funding to increase water supply, improve water quality and create community enhancements throughout the County while supporting compliance with federal clean water mandates and addressing climate change.

For more information: (800) 773-2489.

Sanitation’s Johnathon Truong and Carlos Aldape weren’t the only City employees who recently saved a life.

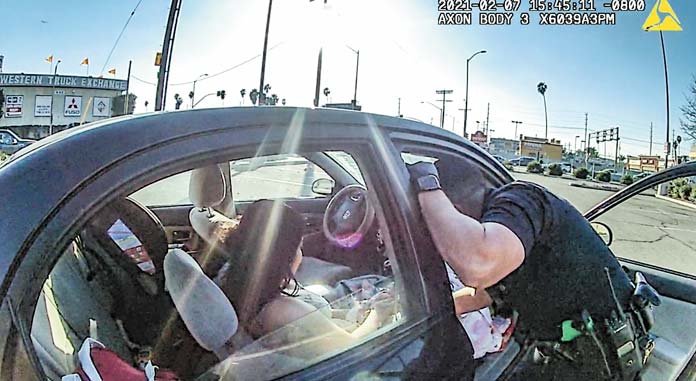

On Feb. 7, Super Bowl Sunday, South Officers Winkler and Diaz heard the Officer broadcast: “Advise the RA (ambulance), she’s giving birth.” The Officers were on patrol when they came across a woman giving birth. Thanks to their quick action, both mom and baby are doing well.

Well done, Officers! And thanks to @LAPDHQ for the heads-up. I

In April 2018, Jesse Hernandez, 13, fell into a sewage line near Griffith Park and was trapped for more than 12 hours before being rescued by a team of employees from Sanitation, the LAFD, the LAPD, Rec and Parks, the DWP, Public Works/Engineering, Public Works/Contract Administration, and other departments inside and external to the City.

The rescue captured the City’s attention. “I thought I was going to die,” young Jessie said after being rescued on Easter Monday.

The LAFD said at the time that it had 2,400 feet of pipe to inspect in its search for Jesse. A manhole cover in a highway median was opened so a camera could be dropped into the pipe. That’s when Jessie was rescued.

The LAFD noted the “excellent teamwork” among agencies that made the rescue

happen.

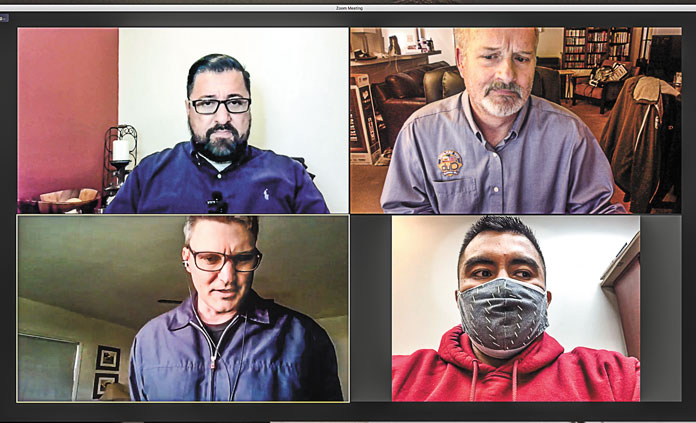

Our Human Duty

On March 9, Club COO Robert Larios and Alive! editor John Burnes interviewed one of the two men who saved a life, Carlos Aldape Torres, Lab Tech, 3 years of City service; and his supervisor, Jon Ball, Environmental Supervisor II, 20 years. The second City employee to participate in the life-saving event, Johnathon Truong, chose not to participate in the interview, although he was happy to be photographed for this story. The interview took place via Zoom due to pandemic protocols.

Alive!: First of all, congratulations for saving a life.

Carlos Aldape: Thank you!

We’ve been doing a lot of big stories on all the great things that City employees have been doing for the past year during the COVID lockdown. But we saw this story we knew it was time to lighten it up a little bit. For the record, Jon, you’re working from home, and Carlos, as a Lab Tech, you still work in the office and in the field. Is that right?

Jon Ball: Right.

Carlos: That’s right.

Good. So Carlos, tell us how you got to your current position.

Carlos: After I graduated from college, I was working at in healthcare and applying for many jobs. I landed in the City applying everybody else online, getting ready for testing, passing the test and then waiting for interviews.

Got it. Okay. Where did you go to school?

Carlos: UC Santa Barbara. Class of 2014.

Are you from LA?

Carlos:: Yes.

Jon, what’s your career path?

Jon: I came to the City as a Water Biologist in 2001. Basically the civil service exams had expired. So to be hired, I came in to what they call the emergency hire process, and I started in the Environmental Monitoring Division, which is basically LA Sanitation’s laboratory facility. I started as a Water Biologist doing toxicity testing on wastewater effluent. I worked in the lab for about five years and then transferred to Watershed Protection, which is dealing with stormwater instead of wastewater, but it involved a lot of the same type of issues. I came over as a supervising Water Biologist, a Sr. Water Biologist, and then over the years I moved into this position as an Environmental Supervisor. I oversee the same group that Carlos is in. We’re the Pollution Assessment Section. We take care of all the water quality monitoring on behalf of the watershed program.

When you’re working in the office, do you both work out of Hyperion?

Jon: We have a small lab facility in our office. We take most of the samples that we collect to the same lab where I used to work, the Environmental Monitoring Division. It’s located at the Hyperion Treatment Plant. They process the samples. Our group will do testing in the field with different instruments and take different kinds of measurements and observations. And when we get the results back from the lab, we interpret the data and report it to the regulators who mandate the monitoring programs that we have.

The Division

The Division

Jon, give us a picture of the Watershed Protection Division and what it does.

Jon: Sure. There are different groups in Watershed Protection, and ours is the Water Quality Monitoring group.

Overall, Watershed Protection is about maintaining and protecting the health of the City’s watersheds. That includes LA River, Ballona Creek, some of our lakes, such as Echo Park Lake, Dominguez Channel and Santa Monica Bay. It’s basically anywhere there’s a stormdrain system that drains from City jurisdiction. That water ends up in those water bodies that I mentioned, so our division’s all about protecting those and ensuring that the health for people who might recreate in those water bodies.

Another group in Watershed Protection Division would be Public Education. That’s all about informing the public of ways that they can help improve water quality and the quality of stormwater runoff and larger environmental issues.

In addition to those, we have an enforcement section that inspects various facilities and businesses that operate in the City of Los Angeles to make sure that they’re following the protocols for reducing runoff and keeping contamination away from the storm drain system.

There are also a lot of engineers and folks who are involved in implementing water quality improvement projects that either capture stormwater and treat it, or capture water and use it for other beneficial uses such as irrigation of parklands and things like that.

I should back out one level and give you a big picture: Our program protects the quality of water in our watersheds, but it also complies with our stormwater permit, a regulatory permit that allows us to discharge our stormwater into waters of the state. And, part of that is all the different programs I mentioned. I need to mention others, too. There’s a Low Impact Development section, which established an ordinance so new developments have to incorporate best management practices that either treat and release stormwater or keep it onsite so that it doesn’t enter into our waterways when it rains. There’s a lot going on.

Yeah. There certainly is. Your compliance, is that with the State of California, with the US federal government or both?

Jon: Ultimately it’s with the EPA, and it’s based on the Clean Water Act requirements. There’s the National Pollutant Discharged Elimination System permit, that’s NPDES. There’s a permit that applies to all of the storm drains in Los Angeles County, and I said, for us to release stormwater runoff into waters of the state, we have to apply and abide by that permit. Ultimately, it’s all about protecting human health and the environment. So that’s the big picture.

Busy Season

Carlos, what are your job duties leading into a major rainstorm like we have this week, and then what do you do during and after such an event?

Carlos: From October to April, that’s our storm season, when we prepare for every rainfall within the City of LA. We have our own monitoring program, which includes what we’re going to be analyzing for, where we’re going to be analyzing, and so on. For example, today we have our own forecast. We use these National Weather Service website. We look to see how heavy it’s going to rain and what time approximately it will start, because sometimes the storm shifts. Then we get a pretty good picture of how it’s going to rain. If it’s going to be in a hard threats area and a 70 percent chance of rain and a quarter inch of rainfall, that’s when we’re going to start to deploy teams to prepare and collect the samples. Usually we prepare all the bottles and all the paperwork. We tell the lab that we’re going to be collecting all these samples by this day, and also we give word to all our supervisors and managers from our group to give us the okay to go ahead. Once we get approval from everybody, we start doing paperwork and preparing bottles and equipment. Our group, which is probably 10 people or 15 people, prepares all of that. Once we’re done with prep, our storm coordinator will tell us to collect samples at a certain time and location. We don’t miss any of the rain.

This is your busy season.

Carlos: Oh, yes.

Jon: We have to collect samples from three storm events per year, and this year has been a pretty tough year because we haven’t had a lot of rain. We have to target whatever storms become available. The equipment that Carlos is referring to is automated equipment that collect samples over time during the course of the rainstorm. That allows us to get a better picture of not a snapshot in time but the amount of pollution that’s coming over the course of the storm.

In a typical storm, Carlos, how many stations will you be expected to monitor or visit?

Carlos: There are a lot. With the auto sampler sites that Jon referred to, I’m going to say maybe 100 or more?

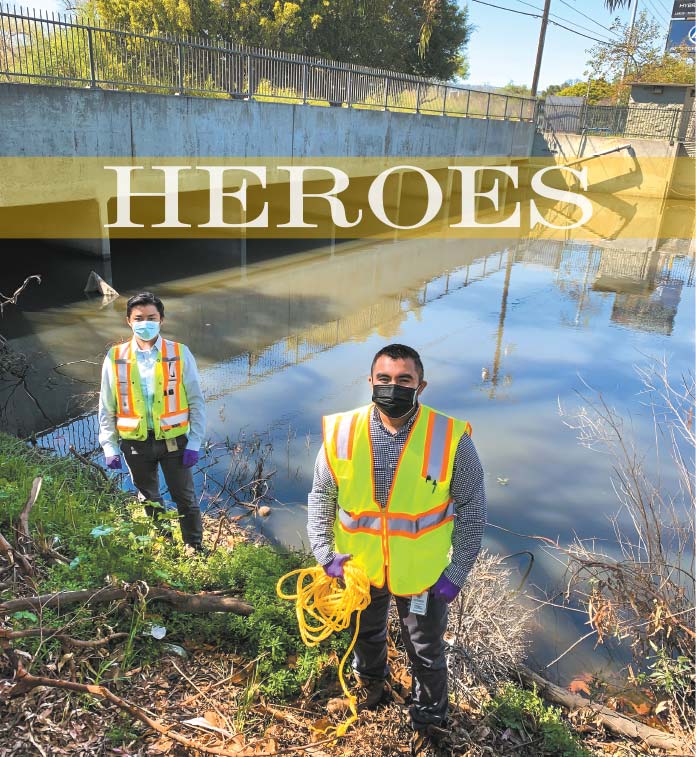

Jon: It’s 35 sites with these automated samplers, and other sites that are not automated. Those require in-person visits during the storm. We split it among different teams, and I think Johnathon and Carlos on that particular day were at the Wilmington Drain, which is a tributary to Machado Lake.

And that’s an auto sampler?

Carlos: Yes, correct.

Saving a Life

That leads very nicely into what happened on that day. Carlos, go ahead and tell us what happened on that day, Jan. 25, when you were checking the automated sampler at the Wilmington Drain, in anticipation of an upcoming storm.

Carlos: We were preparing for storm event number two of the year for us. We went there to do maintenance, but before that we went to Machado Lake to collect water quality samples. Once we finished collecting samples, we went to the Wilmington Drain to check if our equipment was in good shape, if it was properly working and so on.

We parked at the Wilmington Drain near our auto sampler. Once we exited our cars, we heard some screaming something was going on. It wasn’t a simple “help” or something. It was more than one yell.

It sounds like a real struggle was going on.

Carlos: Exactly. It was pretty loud. We barely see people there because it’s gated. That’s why we were worried. We went to look to find out where it was coming from. We spotted this person in the water at the Wilmington Drain, where water gets pooled before hitting the Machado Lake. We saw the person in there, and right away we called 911 to send help.

While you were waiting for 911 to come, what did you and Johnathon do?

Carlos: Johnathon went to go check on the person. Johnathon called out to the man from the shore, but he jumped in only after he saw that the man’s struggling had increased to the point where his head was below the water for longer periods of time. It could have been a fatal situation. There’s a lot of sediment and mud at the bottom of the Wilmington Drain. That mac is very mushy, and you sink in. Sometimes we collect sediment in there to test for toxics or metals.

Did you put waders on?

Carlos: No, whatever we were wearing. Johnathon got into the water. I provided help with rope to keep both of them afloat.

The water was all the way to the chest. I had the rope with me, so I threw it out at them. Johnathon hung onto it, and then the person grabbed onto the rope, too. There was also a bystander there by then. He was helping me bring them to dry land.

What was the man’s condition?

Carlos: Well, I believe he was chugging water while he was asking for help. It was a life/death situation for him.

What do you think he was doing there? Was he bathing? Or swimming?

Carlos: We were asking him questions. He said he was taking a bath. He was hesitating to answer. He had some fear.

And Johnathon ingested some water in his rescue?

Carlos: Yes, that’s what he told us. He went to a doctor, he got tested twice. He went into quarantine, and now he’s doing great.

Happy Coincidence

Are you trained for anything like this to happen? Do you ever think that when you go to a body of water or anything like that, that you might save human life? Were you prepared for this?

Carlos: Actually I was. Before I joined the City, when I was working in healthcare, I was an EMT for an emergency services company.

Wow, really?

Carlos: Yes. During the EMT training, they taught us everything to do in these situations. I have some experience. I pretty much knew what to do.

That’s amazing, that you had a sense of how to take care of things. Had you handled something like this before?

Carlos: Yes, we experienced all kinds of stuff.

Did you ever think that, as a Lab Tech, working in LA Sanitation and Environment, that you’d be using those skills?

Carlos: I was not expecting this, but it’s expect the unexpected!

We presume that this person was suffering from homelessness?

Carlos: Yes, that’s what he appeared to be. He was carrying a suitcase, which he left on scene. When the LAFD was assessing him, he said he was fine and walked away. He forgot his suitcase.

He said he was doing good, and there didn’t appear to be any health issues, so he walked away.

Have you had any contact with him since then?

Carlos: Not really. Since this event happened, I’ve been back to the Wilmington Drain maybe twice, and I haven’t seen him there.

It was probably very scary for him.

Carlos: Yes, maybe.

A Duty

You’ve saved a life before?

Carlos: Yes. At my previous job, working in the ICU, there were cases that went code blue. I was trained for CPR and doing compressions.

Carlos, how does it feel to save a life?

Carlos: It’s a pretty good question. I don’t know, it’s a duty. Some people will say it feels great. I feel very happy that I helped this person, that I helped save his life. But it was my duty to help. It was something I was supposed to do.

Has it made you a celebrity? Have people congratulated you?

Carlos: Yes. When I had my interview with the [LA City View] Channel 35, I had an audience that day. After that, everybody was “good job, man.” It’s pretty cool. When I was working at the healthcare system, that’s what I was doing all the time. You do your job, something that any human being would do.

What do your family and friends say about this experience?

Carlos: They feel very impressed!

Well, it’s what human beings could do, but I’m not sure all would do it. What you and Johnathon did was special.

Carlos: Well, it’s a human duty for us to help each other.

And that’s important to you.

Carlos: It is very important. My parents taught me that you need to help your brothers, sisters, and also your uncles, your family, but it goes beyond that. It’s helping everybody, sparking a chain reaction.

You give, and you get. And it continues. I love that idea.

Carlos: Exactly.

Do you hope people see this as setting an example that they can then give as good as that, to continue paying it forward?

Carlos: Of course. Especially nowadays, with a lot of things going on in the world. Every single instance of helping is very positive in the long run.

I see this as being a very direct example of what you do every day – you are monitoring the water that comes in the rain and then gets into our water supply. That’s good for us, long term. You are trying in the long run to save lives. But that day in January gave you an opportunity to do that very directly. One is long-term, and one is immediate.

Carlos: Exactly, right. At the end of the day, you’re helping someone who is very important.

Jon: I’m really thankful to have both Carlos and Johnathon on this team. It was the perfect pair in this situation. Carlos had a very clear mind, and knew exactly what needed to happen, to call 911, and how to direct them to the right spot. And Johnathon, he’s not here to describe it, but he did a very brave thing, and took a risk jumping in that water. It’s contaminated with fecal contamination and other things. What he did was remarkable, and, in the end, it saved this man’s life. We can play all the different scenarios in our mind, but this had a good ending. This man’s life was saved. I’m really grateful.

Another part of it – our policy is to always send our teams out in pairs. This showed why that’s necessary. It could have gone a different way? I’m really thankful that it turned out the way it did. Johnathon didn’t get sick; we had him tested, and we kept him away from the office for a week or so. I’m really proud of both of these guys, and proud to have them on our team. They took action and knew what to do.

Carlos: Thank you. Part of our protocols, when I was an EMT, was debriefing when something major happened, It was very crucial for us to talk about it and see if there was anything we could improve on. I did that with Johnathon. Everything is okay. He risked his health, getting in the water, and my props to him. He was very brave.

Congratulations again, Carlos. And thanks for sitting down in your busy season to talk to us.

Carlos: Oh, thank you, John, and thank you, Robert, for this interview. I really appreciate that.

Jon: Thank you, Carlos.

Carlos: Thank you, everybody.

|

BEHIND THE SCENES

Club Director of Marketing Summy Lam photographs (from left) Johnathon Truong and Carlos Aldape at the Wilmington Drain, where they saved a man from drowning. |