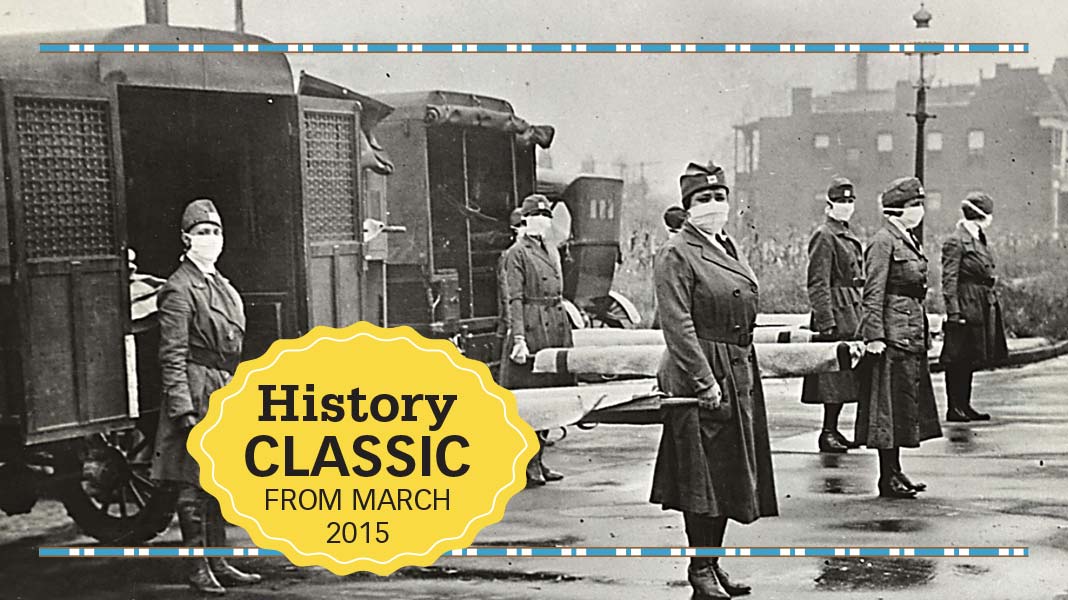

The City suffered as the flu infected the world in 1918.

Editor’s note: In March 2015, when Alive! first ran this great piece, Disneyland was experiencing a measles outbreak. It was a good time to look back at the City’s flu pandemic of 1918 … and of course it’s even more timely now that Los Angeles and the world are gripped in the COVID-19 pandemic. We hope you enjoy this retrospective.

![]()

The story of the recent outbreak of measles at Disneyland and the efforts taken to identify the source has a familiar ring to it. Historical amnesia deprives us of the painful and sometimes tragic lessons learned at someone’s expense in our collective past. That’s a shame. I hope to illustrate my point by reminding all of us about a serious threat that was everywhere in America, including Los Angeles, almost a century ago. I am referring to the influenza epidemic of 1918-19, and I will be using both Council files and the Health Department reports to make my case.

The story of the recent outbreak of measles at Disneyland and the efforts taken to identify the source has a familiar ring to it. Historical amnesia deprives us of the painful and sometimes tragic lessons learned at someone’s expense in our collective past. That’s a shame. I hope to illustrate my point by reminding all of us about a serious threat that was everywhere in America, including Los Angeles, almost a century ago. I am referring to the influenza epidemic of 1918-19, and I will be using both Council files and the Health Department reports to make my case.

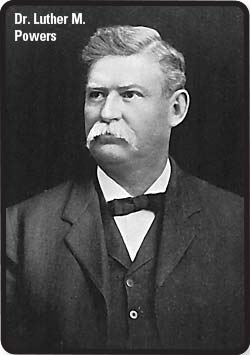

The City’s Department of Health was led by Dr. Luther M. Powers from 1893 until his death in 1924. Dr. Powers oversaw a variety of programs that tested food, milk and water samples for safety, conducted health screenings and treatment in the City Jail and also advocated for public toilets for the indigent. Every year, the annual report condensed the public health of the City into a series of reports submitted by the various divisions, including Infant Welfare and Milk Inspection. The reports reveal how the concern for public safety conflicted with the rights of private citizens and industry during the flu crisis.

The City’s Department of Health was led by Dr. Luther M. Powers from 1893 until his death in 1924. Dr. Powers oversaw a variety of programs that tested food, milk and water samples for safety, conducted health screenings and treatment in the City Jail and also advocated for public toilets for the indigent. Every year, the annual report condensed the public health of the City into a series of reports submitted by the various divisions, including Infant Welfare and Milk Inspection. The reports reveal how the concern for public safety conflicted with the rights of private citizens and industry during the flu crisis.

There have been several books written about the 1918 influenza outbreak and its devastating effects around the world. The Great Influenza by John M. Barry is one that puts the global impact in perspective. Our 1919 Health Department Annual Report, from Box B-1059, is more of a snapshot composed of what was known or believed to be true at the time. This is the road map I’ll be using.

“This disease was introduced into Los Angeles by an infected training ship…after Sept. 15, 1918, and also from infected tourists…” begins the report. The Health Department was caught off-guard as the first patients arrived at the General Receiving Hospital on Sept. 22. The mayor’s office reacted quickly by establishing not one but two committees. One committee was composed of doctors and the second of business and public safety entities. The Health Department’s accounting division reported that the first emergency hospital at 936 Yale St. was up and running within 48 hours. “We were called upon to equip a hospital when equipment and supplies were extremely scarce and deliveries problematical.” Remember that the First World War was still being fought and medical supplies and gasoline were prioritized for the war effort. Two other hospitals were established in San Pedro and Mount Washington despite concerns from local citizens about having them in their neighborhoods.

Mayor Frederic Thomas Woodman declared a state of emergency on

Oct. 11.

As I read the report, I was struck by how quickly the City got things done to combat the virus. The City Council was quick to approve funding for more nurses and facilities to deal with the flu. They also passed Ordinance 38522, on Oct. 10, to quarantine the citizens by closing schools, theatres and other public gatherings to prevent the spread of the virus. The quarantine report details other measures: funerals being private instead of public affairs, and the closure of poolrooms and auction houses. Café entertainment was prohibited. A “stay at home week” was proclaimed, and factory work schedules were staggered to prevent crowding on streetcars to reduce the odds of transmitting the illness.

But there was pushback over inconsistent application of the rules laid out in the quarantine ordinance. Movie theatres were closed (causing most studios to suspend production and distribution), but stores and restaurants were allowed to stay open. The Theatre Owners Association (TOA) sent a petition to the Council in file # 2220(1918), demanding that the theatres be reopened and all citizens compelled to wear face masks instead. They argued that the “incomplete closure law had allowed influenza to increase 500 percent since Oct. 10.” Likewise, the Merchant and Manufacturers Association protested that any action to restrict access to stores to appease the TOA was “unpatriotic, unfair and unjust.”

The opponents had a point. The quarantine report contains this statement: “Interpretation of the closing ordinance presented daily problems. Music was stopped in cafes – should the demonstration of phonographs be permitted? Schools were closed – should this include music teachers giving lessons in studios…the Department sought at all times to avoid discrimination and to enforce the ban with as little discomfort and financial loss as possible.”

In early December, Dr. Powers responded with the Health Commissioners request that the TOA petition be granted, as the number of reported cases had dropped. The ordinance was rescinded on Dec. 2. However, an almost immediate resurgence of infections brought about a different approach that sought to limit exposure from the home.

Badge-carrying health inspectors and LAPD officers were given broad powers to place a house under quarantine, preventing anyone from entering or leaving. Some 4,036 buildings were quarantined in Los Angeles during December 1918 alone.

The report includes details of the role played by the Health Inspectors. More than 350 strong, they covered 100 distinct neighborhoods throughout the City “running errands, deliver[ing] groceries and otherwise minister[ing] to the needs of families in quarantine.” Many of the inspectors were returning soldiers from the battlefields. Special effort went into identifying sick passengers arriving at railway stations for treatment and isolation. Streetcars and taxis were inspected followed by regular disinfecting treatments.

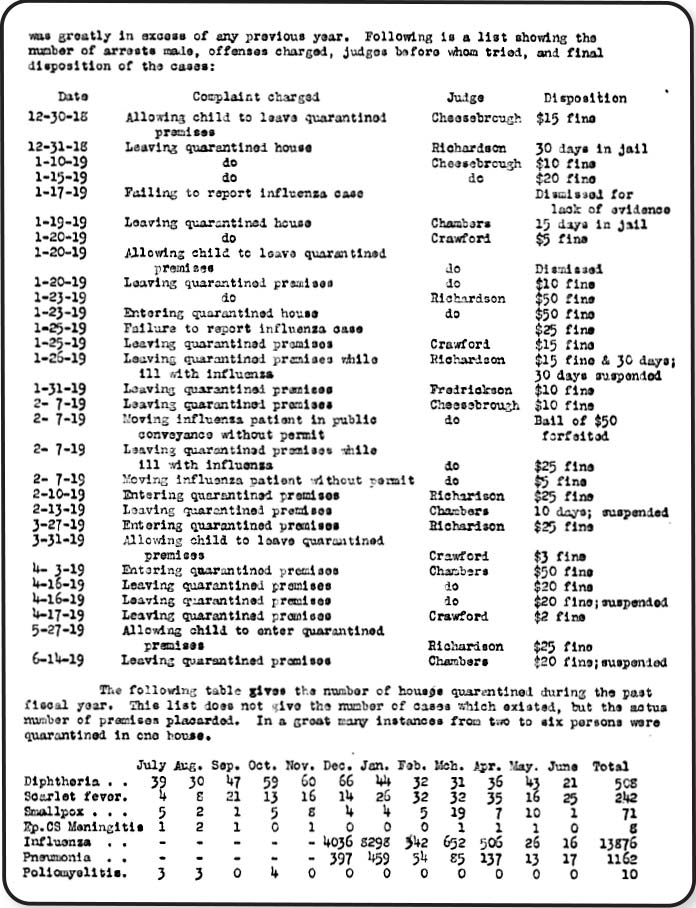

Ethnic communities – not named in the report – were described as being difficult to manage due to language issues and customs including large public funerals and parades. One social club had its entire membership quarantined at the same time. The penalties for violating the quarantine ranged from a $15 fine up to 30 days in jail. There were 29 cases taken to trial between Dec. 30, 1918, and June 14, 1919. Most were settled with the fines or a few days in jail. The number of quarantined buildings reached 13,876 during that same time.

The 1918-19 annual report listed 57,774 reported cases of influenza. Dr. Powers believed that this was less than half of the actual cases due to under-reporting. There is a statistical sheet in the report that converts all deaths citywide into specific categories including age, race and place of birth. The most likely influenza victim during 1918-19 was a married white male aged 20 to 45 years. Infant deaths numbered 53, and deaths of people aged 65 and over reached 63. The death toll attributed to the flu as primary or as a secondary factor between September 1918 and May 1919 was 3,482. The 1920 annual report described a resurgence of influenza in January of that year, with 9,147 cases recorded and 239 deaths. The City of Los Angeles recorded 17,863 deaths from all causes within this two-year period, and the total death toll by the flu was 3,721, just more than 20 percent.

The National Archives Website (www.nara.gov) estimates that 50 million people worldwide died during the pandemic of 1918-19. This was a time when people traveled by ships and trains, and many of the medical advances we rely on didn’t exist.

Two ironies that caught my attention as I was finishing the research for this story were that, during the flu outbreak in Los Angeles, not one death from measles was listed in the statistics. The second was that an LAPD officer who had just returned from fighting in France died of influenza while serving as a quarantine inspector.

The pandemic of 1918-19 proves that the adage is still valid: “They who forget their history are doomed to repeat it.” Stay healthy.

![]()