LA

Bureau of Engineering’s Shelter and Housing Program – developed quickly to help get the growing number of Angelenos suffering homelessness literally off the streets into humane shelters – is a story of talent and technical know-how, unexpected journeys, and personal transformation.

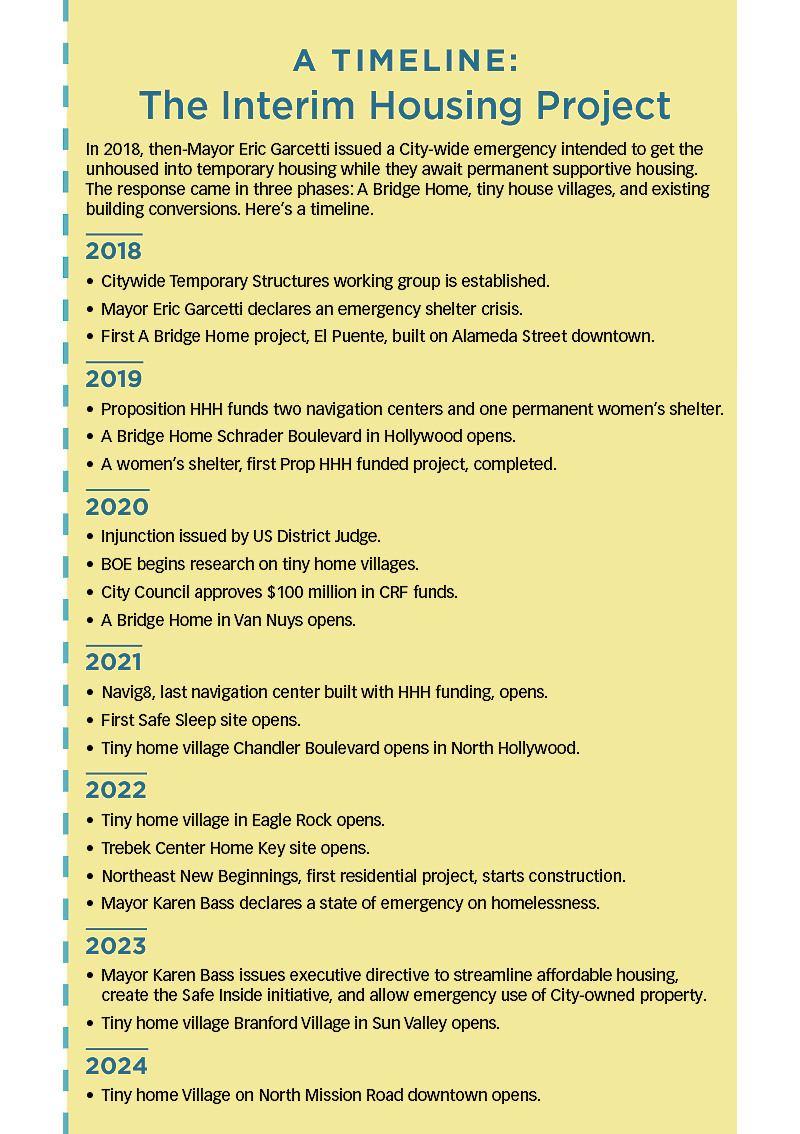

In 1998, then-Mayor Eric Garcetti declared an emergency shelter crisis due to the burgeoning numbers of LA citizens suffering homelessness and living on the streets. He asked many City departments to step up to the crisis and take action to help those homeless citizens. Public Works’ Bureau of Engineering was tasked with a major role of designing and then managing the construction of new interim shelters, and the new Shelter and Housing Program was created. Principal Engineer Allan Kawaguchi led the early efforts.

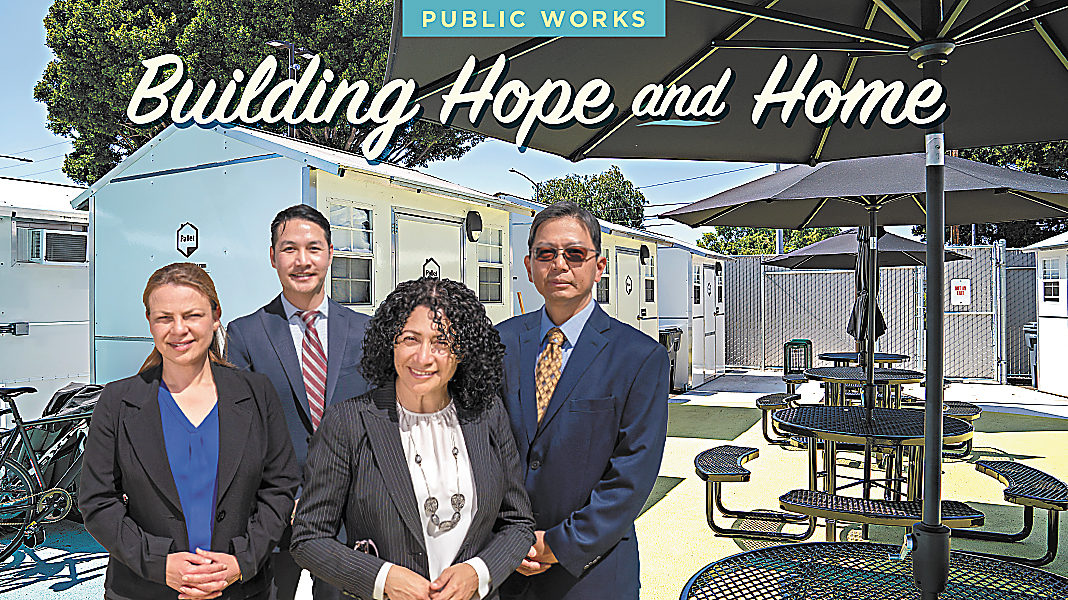

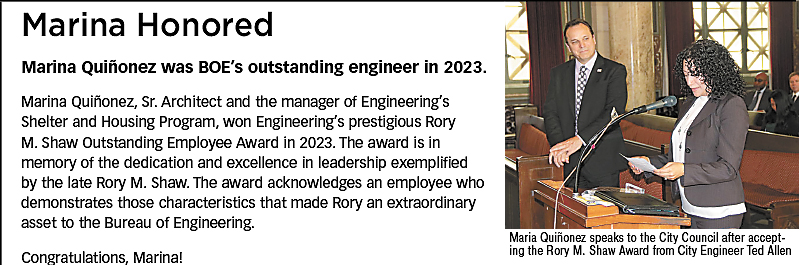

Now the dedicated team is led by Marina Quiñonez, Sr. Architect, and advised by Mariet Ohanian, Civil Engineer; Son Vuong, Electrical Engineer Associate III; and Raymond Huang, Building Mechanical Engineer.

Engineering’s Shelter and Housing Program team works with various City departments, agencies and Council Districts across Los Angeles to create interim housing solutions to address homelessness. The various types of housing include Phase One, A Bridge Home (congregate living, double and single occupancies); the current Phase Two, tiny home villages; and the upcoming Phase Three, units potentially designed for families and building renovations.

In September 2018, the first congregate living model was built as A Bridge Home project called El Puente in the El Pueblo area. This pilot project provided 45 interim beds and shared hygiene amenities.

In 2019, Prop HHH allocated funds for homeless housing and services and funded three Navigation Centers, which cater to a demographic of people who reject housing but are in need of hygiene, laundry and case management services and storage. Prop HHH also funded a women’s shelter in Council District 4. This building, a decommissioned library, had a trauma-sensitive design, and provides case management and hygiene and laundry services to 32 women.

In March 2019, the first A Bridge Home (ABH) project was completed in Council District 13. The Bureau of Engineering built 16 locations in multiple Council Districts throughout LA over a period of 16 months. ABH projects are a congregate living model, with men and women separated within a membrane structure, giving each individual a sleeping module with a bed, cabinet; pets are allowed. The amenities on site are hygiene, laundry, admin services for case management and outdoor sitting areas with shade umbrellas. A total of 1,360 interim beds have been provided.

In January 2021, Navig8, the last of three Navigation Centers using HHH funding, was built in Council District 8, and the first Safe Sleep site was completed, which provided single or double occupancy tents, daily meals, case management, and hygiene and laundry services.

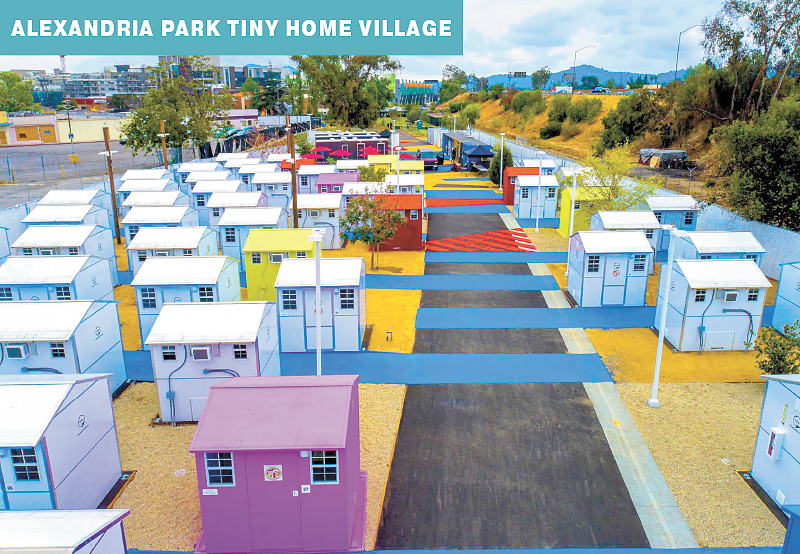

The first Tiny Home Village in the current Phase Two was built in Council District 2. These facilities have single or double sleeping accommodations, and provide case management, hygiene and laundry services, and daily meals. There is a low barrier to entry, and there are amnesty lockers and a pet area. Exterior communal spaces are also provided.

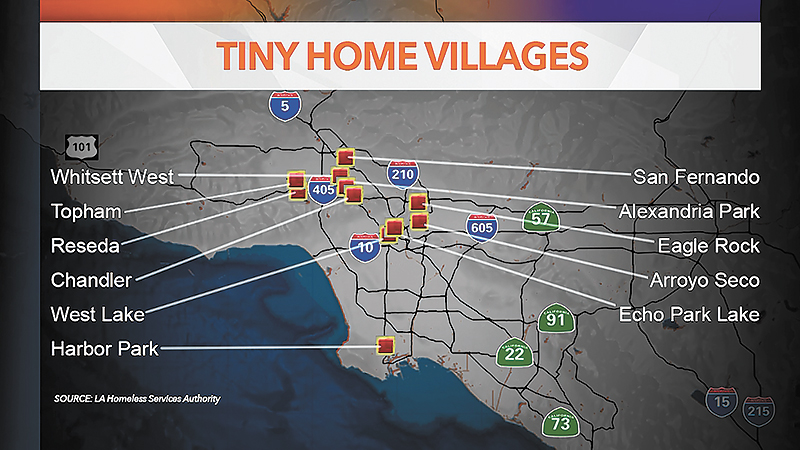

Since 2022, the Bureau of Engineering has now delivered 12 villages, providing 1,552 interim beds. The Shelter and Housing Program also assisted in building a Home Key site in Council District 12. The site is a congregate living model and offers case management, hygiene and laundry services, and daily meals. Finally, in Council District 1, the team opened the first residential project, New Beginnings (Phase Three). This has multiple occupancy accommodations that could accommodate families, case management, hygiene and laundry services, amnesty lockers, pet spaces, and communal areas.

As of Spring 2024, Engineering has delivered a total of 40 projects for Homeless Services and Housing throughout the City of Los Angeles for a total of 4,078 interim beds.

In this issue, read an interview with the Shelter and Housing Program team about their unexpected journey toward helping the homeless through design and know-how, and about how it changed them.

We thank Marina, Mariet, Son and Raymond for their time, information and candor, and Mary Nemick for her assistance. •

Architecture as Advocacy

On April 16, Association CEO Robert Larios and Alive! editor John Burnes interviewed the Public Works/Engineering team that designs and manages the construction of the City’s Interim Housing project, intended to get the unhoused off the streets and into temporary housing while awaiting permanent supportive housing. The team includes Marina Quiñonez, Sr. Architect and manager of the Shelter and Housing Program, 18 years of City service; Mariet Ohanian, Civil Engineer and construction manager of the Shelter and Housing Program, 18 years, Club Member; Son Vuong, Electrical Engineering Associate III and electrical engineering adviser, Shelter and Housing Program, 8 years; and Raymond Huang, Building Mechanical Engineer and mechanical engineering adviser, Shelter and Housing Program, 18 years. • The interview took place via Zoom.

What’s been your path? Where did you enter the Bureau of Engineering and then get to where you are now?

Marina Quiñonez: I started with the Bureau of Engineering as a student intern during my undergrad years at Woodbury University. I stayed working as a student intern through my Master’s program at UCLA. During my internship, I saw the impact of design in various communities with the projects that I was involved with, and I realized that working for a public agency would allow me to have more opportunities to interact with various demographics, and that’s how I ended up here.

I started as an Architecture Associate I, then a II, then a III, and then a full Architect. After that I became a Sr. Architect.

Same question for you, Mariet.

Mariet Ohanian: I went to college for a couple of years, then I decided to join the Army. After my military service was over, I went back to school to be a civil engineer. When I finished school, I decided to work for the City because I live in the City, and I like civil service work because it has a variety of projects and there are different things to do; it’s not just one type of project. I got hired as a Civil Engineer Associate I, was promoted to Associate II, then I was an Associate III for a short time before I was promoted to a Civil Engineer.

Son Vuong: I started in the naval nuclear propulsion program, working on submarines for the U.S. Navy. During that time, I fell in love with engineering, so I went to university afterwards to study electrical engineering. The Bureau of Engineering is my first job after I graduated college. I started out as an Associate I, and then I moved to II, and now I’m an Associate III.

Raymond Huang: I have been in the field of engineering for more than three decades that crossed different subspecialities. In the first decade of my engineering career, I worked as a maritime engineer in commercial ships that had taken me across the globe, then I followed with a pursuit of working as an aerospace engineer. After I earned my Master’s degree in aerospace engineering from Cal State Long Beach, I was offered a position with the City and thus began my journey as a building mechanical engineer. My career has taken me from the seas to the skies; I’m thankful to say I’m now safe on land! Since starting my career with the City, I’ve risen through the ranks from a Mechanical Engineering Associate I, II, and III. Today, I’m a building Mechanical Engineer.

From the sea to the sky to the land. I like that kind of concepting!

A Bridge Home, to Start

A Bridge Home, to Start

Tell us what A Bridge Home is all about.

Marina: Sure. The City has established a Shelter and Housing program. It encompasses all of the interim housing within the City. It was initially established when Mayor Eric Garcetti declared an emergency crisis in 2018. The first phase of our program was the A Bridge Home program, which was a congregate living model, meaning that there were no separate walls, people slept in “sleeping modules,” a cubicle-like bedroom space with shared hygiene amenities. That’s essentially what A Bridge Home was. It was a bridge from the streets to permanent supportive housing.

We’ve moved forward to phase two, which is focused on tiny home villages and providing more privacy for individuals. The Bureau of Engineering has been responsible for establishing the design standards, project design and construction management. We have established design guidelines with the help of Son, Raymond, Building and Safety and the Los Angeles Fire Dept.

|

‘A Bridge Home’ Projects A Bridge Home was the City’s first phase of response as it ramped up its efforts to manage the unhoused community in 2018.   |

What have your responsibilities been in the first two phases?

Marina: We’ve been designing with an in-house group of designers. We have architects and engineers in-house. We also project-manage our consultants. The whole process is very fast tracked, so we need assistance. Construction management is Mariet’s expertise. She and her team have managed construction from phase one through phase two and a lot of other facilities we’ve built.

It all started with establishing design guidelines within architecture, electrical, mechanical and structural engineering. Establishing those guidelines helped the process to be fast-tracked during design. And having guidelines established with Building and Safety allowed inspections to go much quicker. We’ve established the foundation for this fast-track process to work.

How did the team come together? Did you volunteer to switch to this emergency-needs project, or were you assigned?

Marina: Some of us were “voluntold”! It was assigned as the next project. I had just finished construction for the new Woodland Hills Rec Center, and I needed a project. So my supervisor at the time thought, “Marina, there’s this homeless-related project…”. It was just one project at that time; no one knew it was going to be this big and develop into a program. I was given the one project to manage. Then it became two and three. Then it really exploded into the program we have now, where we’ve delivered so many projects within four to five years. Once our Principal Engineer, Allan Kawaguchi, retired, I took over the program, which has been exciting and stressful.

Raymond Huang: I am always available to support my colleagues in the mechanical engineering aspect of projects. Having worked on multiple projects with Marina, I ensure her ideas turn into tangible solutions. When I was asked by my supervisor and Marina to provide mechanical engineering support for this exciting assignment, I was greatly motivated to be part of the team.

Son: I was actually new, just two years in. I had just gotten my license. I have been learning Revit, which is the primary tool used for 3D modeling for the first two years I was here. This opportunity came up and they asked me if I wanted to work on it. I also thought it was going to be a one-off assignment, maybe one or two projects. But it expanded to be so much more.

Mariet: At the time I was also managing construction of a recreation center. Allan said, “We need help with construction management,” and my Principal Engineer asked me if I wanted to look into the homeless shelters because they were a different type of construction. I said, “Sure, that would be interesting.” I got involved and I’m still here. That’s how I got involved.

Update us, please – how many villages, how many residences, how many people have been sheltered?

Marina: So far, we’ve completed 40 homeless-related projects, and we’ve spent over $200 million in total project cost. We’ve created 4,078 interim beds. People are supposed to live there six to nine months, and then the hope is that they’re placed into permanent supportive housing. So we hope the 4,078 interim beds will house many more people than that over time. We built about 16 A Bridge Home projects. Then we built 12 tiny home villages. So far, we have six more in design, and we also have another residential site that’s in design. We’re looking to move into phase three – more tiny home villages and existing building conversions. We’ll see how that develops.

Other than A Bridge Home and tiny home villages, we’ve also built safe sleep sites, which are parking lots we’ve converted to areas where service providers can bring pitch-up tents. Instead of being on the street, the unhoused are in a safe environment. We’ve also been involved in some home key sites, residential typologies, and also building conversions. It’s been multifaceted because the City understands that some people don’t want to be in a specific environment; some would rather be in the streets. I think providing a multifaceted approach has helped us to reach specific demographics that perhaps weren’t open before to being in a “homeless shelter,” whatever that means to them. We’re trying to have different ways of addressing what a house looks like for someone so that they’re more open to being helped and receiving services. We’re also looking at how to serve families; we have one site built and one in design for families.

Son: All of our facilities are electric-only. We started building them in February 2018 – our first homeless shelter is in downtown LA across the street from Union Station. Our design team made a conscious decision to make all the new construction electric before any policies were in place to mandate it. They don’t produce natural gas emissions.

Tiny Home Villages

Tiny Home Villages

What does a tiny home village encompass? What does it contain?

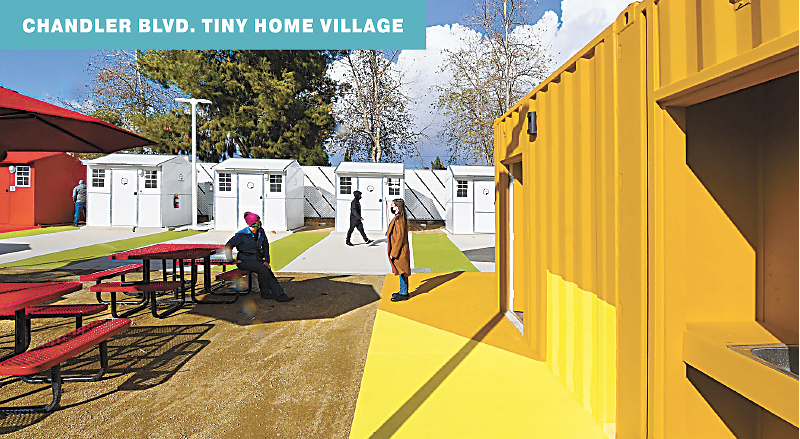

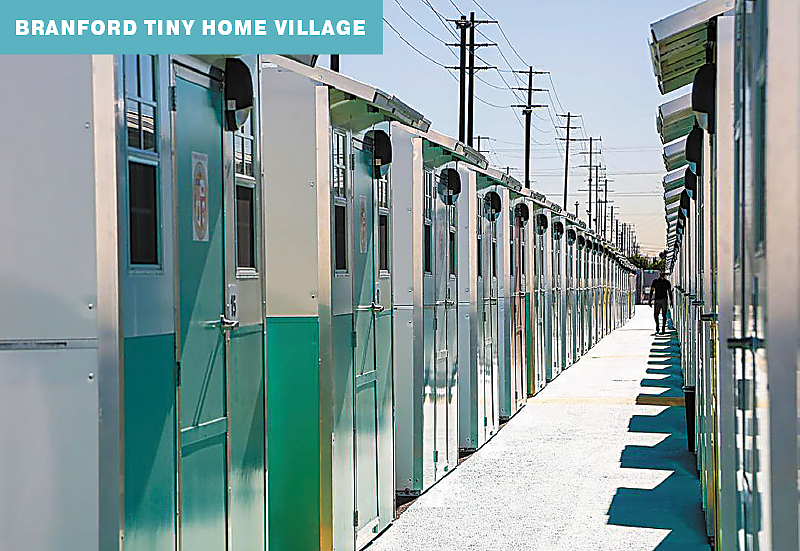

Marina: A tiny home village is a community – our hope is to build community within that village. It encompasses sleeping cabins that are 64 square feet, about eight by eight feet, for single and double occupancy. The amenities are shared as far as hygiene. There are restrooms and showers on site. There’s also a laundry facility, and there’s case management. Three meals a day are delivered to the site. We have areas where people can sit and have a meal together. The hope is that a tiny home village brings more dignity and privacy to an individual who’s lived on the streets.

A true community model of everything that they might be experiencing when they leave.

Marina: Correct.

How long do they stay in their residences in the tiny home villages before moving on?

Marina: It has varied. The Bureau of Engineering doesn’t get involved past construction, so we don’t know exactly how long they stay. But our hope is that they are there six to nine months, and then they get placed into permanent supportive housing. Permanent supportive housing hasn’t been built as quickly as we’d hoped, and so I would imagine that people are staying a little bit longer, but we don’t know the exact length.

Do the individual shelters come prefabbed? Are they built on site?

Marina: Yes. They’re panelized and fabricated at the warehouse. Then during construction, once the site is ready, they get delivered and assembled on site.

History

History

How did the project start and develop? It was a response to the homeless crisis, but was it a quick development?

Marina: The mayor’s office asked the Bureau of Engineering to investigate a product called Pallet Structures. That was in early 2020. The standard plan for the tiny home village was established with two pilot projects requested by Council District 2 during an injunction. The City was sued by LA Alliance. There was an injunction in 2020, then also during the rise of COVID-19, the Council office approved $100 million of COVID-relief funds in July 2020 to create these tiny home villages. The selection of sites started shortly after that. It was a very interesting time of litigation and COVID that really exploded the amount of tiny home villages that were built in 2021-22 and now ’23-’24.

I’m sure you worked as hard as you possibly could to turn it into reality despite the challenges.

Marina: During that time, we also had other homeless projects. We deployed RVs during COVID. Son, Mariet and I were out there with our masks and it was a very interesting time. We had to keep the City moving and we had to continue housing people. The team really came together during that time.

Mariet: COVID created one major challenge for construction, at least for us. We started having issues getting supplies, especially electrical equipment. All our switchgear and panels were delayed for more than a year. It was taking way longer than we expected. These projects were supposed to be done in four to five months, but they ended up being extended more than a year or a year and a half sometimes because we couldn’t get equipment. That created a major challenge for these projects.

How did you overcome the challenge?

Mariet: We tried some workarounds. We started looking into other companies that could build the equipment rather than just ordering it pre-made. We were lucky sometimes to find companies that could provide us with what we needed. We also learned that if we expand on some of the requirements, we have more options, which will save us some time and fast-track the project. But overall, it still impacted our project. We were not able to solve all the problems.

Son: Some of the products like lighting, we would have to let the distributors know about a year in advance that we might be purchasing them. A lot of them helped us out by stocking them ahead of time or even prioritizing our orders. A lot of our project managers wrote letters to these large companies that manufactured panels and equipment for us, letting them know our situation and our needs. A lot of them were very helpful in expediting our order, or even getting us ahead in the line.

Another challenge during COVID was plan check. Traditionally, we would print out these plans on sheets that are two feet by three feet. We would bring them into Building and Safety, the LAFD, the LADWP and other utility companies to get them reviewed, and we’d have to submit the paperwork. During COVID, they weren’t interacting face to face, and the documents we submitted were being quarantined for about two weeks. We lost some time there. We had to work with the different utilities and building departments to change the way we did things. They allowed us to submit electronic documents, which helped a lot and saved a lot of time and paper. It was very helpful that the departments were flexible and worked with us.

Raymond: My forte is domestic water and sanitary sewer infrastructure. Most of the time, when we try to figure out the perfect location to build a shelter, the next biggest problem is where the water will come from and where the sewage will go. Sometimes we have a perfect location to build a shelter, but the water and sewer infrastructure are not readily available. During times like these, we did a lot of additional planning and spent vast resources to overcome these challenges

Is this project a national model? Have other cities looked at the way this is happening in LA?

Marina: Yes, the City has been approached by various cities to understand our process. We’ve shared drawings, we’ve shared our ordinances and our executive directives. We’ve shared a lot of those templates with other cities, and [supplier] Pallet Structures expanded with new business after they worked in LA. There’s been a movement, I believe, nationwide to see our perspective on the tiny home villages and their meaning. We’re providing community, not just a bed. Adding color and vibrancy to our villages has informed other cities. Also, our sense of safety. We give fire life safety a high priority when we’re designing our villages. We’ve seen other cities have incidents where the pallet shelters go up in flames. We hope that they’re also learning the importance of fire life safety.

Lessons Learned

Lessons Learned

What have you learned from these important projects?

Raymond: People often criticize bureaucracy. But, in the past few years that I’ve been working on this homeless shelter program, I have been blessed to work under dedicated and passionate leadership, such as Marina or our previous program manager, Allan. With this strong leadership, we have been able to combine City resources and make this bureaucracy work for both our program and the City. Through our combined efforts, we can achieve success. To this day, it blows my mind how we’ve managed to complete homeless shelters in less than three months, showing the tangible results of people from diverse backgrounds coming together to work on a common goal.

Mariet: We learned a lot, especially how to work together with all the departments and move projects forward, as Raymond said. One of the issues that Raymond mentioned, for example, was getting utilities to all the sites: We found that it’s beneficial to get utilities at least to the property line before we award the contract to a contractor to build the project. We have been working with LASAN and LADWP to bring the utility meter or the sewer connection point to the property line so we have everything ready before starting the project. The cooperation of all the departments and all the agencies in doing the work in advance has helped move these projects forward a lot faster than it traditionally would.

Marina: I can echo the idea of learning to work together as a City. That’s been a great thing that happened through this process. We’ve delivered housing in record time, like Raymond said. As a whole City, we worked departmentally– LADBS, LA Fire, LADWP, Sanitation—they’ve all been great partners in successfully delivering these projects. Their staff worked diligently as well, for the LADWP to give us commitment letters at the speed that they’ve done. That has been really great.

But I think one thing specifically that I’ve learned beyond that is that I really do work with great people. The people within our division and three or four other divisions have been involved in the homeless program. Raymond, Son and I are in the architectural division. Mariet is in the Construction Division. The Environmental Division does all our CEQA processes. Our Geotech Division does a lot of our site borings, environmental or soils investigations, things like that. The Structural Division and our Survey Division, so many good people. But, more specifically, in our smaller circle, I work with great staff. We work together well. There’s a collaboration, a camaraderie that we’ve built within our group that I think is great. That can never really be replaced. The journey of delivering projects has led to friendship that’s very valuable.

Have you grown as a person because of this special project?

Marina: I can share something I’ve reflected on – to house our unhoused Angelenos has been quite a journey. To understand the impact that design has in communities is really important to acknowledge, but beyond architecture, it’s bringing someone home. Hearing stories about lives that are being changed affects you; you grow in gratitude to understand that someone’s life was completely altered by a decision they made. A lot of our unhoused Angelenos are not drug addicts. They’re not mentally ill. Some of them just had life situations that just didn’t go well; I could be one of those people in an instant, if my life changed in the way that some of them have experienced. It keeps you with a level of gratitude that is beyond what I’ve understood before. I am part of a church and we help the unhoused through organizations, but being hands-on now in this project, I try to understand what they need through case management or through talking to them. It puts me in a different space to understand that our unhoused people have a past and they have a story. I’ve been blessed to understand that path now in a different way.

Mariet: Most of the time, when we build these projects, the Bureau of Engineering is involved with designing and building this project, but then we pass it on to the service provider, which provides for the residents. We are not overly involved in the personal management of the residents. But a woman came to speak at one groundbreaking ceremony. She was a resident in one of the shelters, and she shared her story. She said that she fell into hard times. She became homeless. She was on the streets for a few years. Then she noticed that we were building one of the shelters in her neighborhood. She signed up and got a spot in the shelter. She got the help she needed. She got help for her addiction. She went back to school and got recertified as a nurse. She went back to work. She found permanent housing, and she was back to her life. Hearing her story was very inspiring. Knowing you can change people’s lives just by providing safety and a place where they can get their life together is empowering. Most people just need that little help to move forward. That makes you feel good that you can do that for someone.

Son: Aside from the Bridge Home and the tiny home villages, we produced other products too. We did tenant improvements on existing buildings. One in particular was a project in Hollywood for women who suffered from domestic violence. It was an old library that one of our architects, Erik Villanueva, helped bring back to life. It’s a gorgeous place. The clients there, individuals who suffered a lot throughout their lives, had no place to go. It was great to see that they now had a place.

Another product we delivered were refresh centers, or navigation centers. One of the refresh centers is in Skid Row. When we were going there to look at the new site, I saw somebody on the street washing their clothes in the gutter, using whatever water was left there. It was really heartbreaking. Months after that, we were able to build a space where they could do their laundry, pick up food, have a safe place to hang out, and have a little bit of their freedom and dignity back.

Raymond: When I participate in the grand openings of these shelters, I feel a sense of joy and purpose as I provide shelter to the most vulnerable in our communities. I feel their hope and draw motivation through making our community a better place. Moments such as these remind me of why I chose my career path. While many think engineers tinker in offices doing much of their work on computers and drawing boards, we bring ideas to life. Changing lives is why I love my job.

Marina: Recently we opened a site at 850 Mission. The Councilmember dealt with a specific demographic, which is mariachis. His district has a group of mariachis who are unhoused. He had them play at the grand opening. That’s just one example that homelessness really can touch anyone in any demographic. But him being able to highlight that at the grand opening was quite special and to give them the opportunity to share their art with everyone present was really touching as well. At every grand opening, there are people who share how our projects changed their lives. That’s really impactful.

‘Just Feels Good’

What do you love about what you do?

Raymond: I love the intensity and pace at which these projects are completed. Because we must help those most vulnerable in our community, these projects are completed swiftly and with the utmost competence. This project has allowed me to see my designs come to life in a short period, something that I find very satisfying. For context, this contrasts with a typical city project which might take one, two, or sometimes even three years to become reality. Despite this, what brings me the most joy is bringing hope to those most vulnerable in our communities by creating centers for these individuals to seek help and redirection.

Marina: As an architect, I can use design as advocacy. Every time I put a design together, I know that it’s going to end up helping someone. Going through school and deciding to be an architect, I never thought I would be housing the unhoused, but it’s a form of advocacy.

Son: I’ve been fortunate to work with this great team who are passionate about helping the public in so many different ways. There are things I never thought about in the past, like art – how art and color could be so important to the built environment. When we go through engineering school, we get taught about functionality and whether it’s cost effective or not. But the architects who we work with have been able to bring in another layer, another way to view things. It’s not just about how something functions. It’s about how people feel and how people connect when they are there, and whether they feel safe. It’s been very rewarding in that aspect.

Mariet: Most of us chose to work for the City because we want to improve the lives of people in the community, and by working on the homeless shelters, which I don’t think any of us imagined that we would be doing, there is a different level of satisfaction; it just feels good. When I see someone on the street, I think about the projects I can complete to help that person and provide safety for them. I love doing that service and finding ways to do it better and faster, helping the team achieve whatever we can.

Well Marina, Son, Raymond and Mariet, thank you for taking the time to tell us your story on helping to house the unhoused. We thank you and appreciate all that you do for the City of Los Angeles.

Mariet: Thank you for your interest in what we do, and highlighting it.

Our honor.

Raymond: Thank you.

Son: Thanks! •

|

BEHIND THE SCENES  Club COO and photographer Summy Lam (right) photographs some of the 50-plus Chaplains in the LAPD Chaplains Corps, at the LA Police Academy entrance plaza. |