Photos by Summy Lam, Club Director of Marketing, and courtesy City Planning

The Office of Historic Resources protects the best of the past to enhance a strong urban future.

Notions that LA has no real architectural and cultural history couldn’t be more wrong. Proving that is the job of Ken Bernstein, Principal City Planner and Manager of Los Angeles City Planning’s Office of Historic Resources.

But he’s after much more than just proving an old stereotype wrong – he’s using neighborhoods of bygone eras to build a better future for the City. He’s leading the City’s efforts to preserve the historic cores, update them judiciously, make them more equitable, build resources to support them, and put them to use to make a stronger Los Angeles for today and tomorrow.

About the Office of Historic Resources

Los Angeles’s remarkable architectural and cultural heritage boasts examples of styles from the Arts and Crafts movement to mid-century modern. Historic places throughout the region contribute to the City’s rich social and cultural life.

Los Angeles City Planning’s Office of Historic Resources (OHR) works to protect, enhance, and revitalize the City’s historic places through its comprehensive, state-of-the-art, and balanced historic preservation program.

The Office:

- Serves as the professional staff for the City’s historic preservation commission, the Cultural Heritage Commission,

- Oversees the City’s 35 historic districts (Historic Preservation Overlay Zones, or HPOZs), encompassing more than 21,000 properties,

- Manages the City’s major financial incentive for owners of historic properties, the Mills Act Historical Property Contract program,

- Integrates historic preservation into Los Angeles’s long-range planning and development project reviews,

- Manages the City’s historic resource inventory, HistoricPlacesLA, which includes the findings from SurveyLA, Los Angeles’s first-ever Citywide survey of its historic resources,

- Serves as an expert resource on preservation within City Planning and for other City departments, and

- Provides responsive customer service in conducting historic preservation reviews.

Let LA’s beautiful past be your guide as we talk about preserving our heritage and restoring it for a more robust, equitable future.

A note about this month’s feature: Alive! began producing this look at City Planning’s Office of Historic Resources in February 2020, a few weeks before the pandemic hit. We shelved this story until it was safe to bring it back, which we’re doing now. We’ve updated the contents to include issues related to COVID-19. All photos were taken prior to the pandemic taking hold. – Ed.

He Wrote the Book

He Wrote the Book

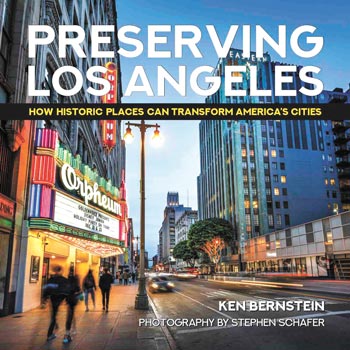

The City’s Principal Planner, Ken Bernstein, published a book during the pandemic on historic preservation.

In addition to adjusting to the new ways of working during the pandemic, Ken Bernstein also completed a new book, Preserving Los Angeles: How Historic Places Can Transform America’s Cities, released by Angel City Press in April. The book landed on the Los Angeles Times nonfiction bestsellers list in May.

Preserving Los Angeles expands upon the topics and themes discussed in this interview, describing and illustrating the comprehensive story of how historic preservation has revived Los Angeles neighborhoods, created a Downtown renaissance, and guided the future of the City. Bernstein showcases Los Angeles as a model for other cities, demonstrating how preservation can extend beyond the preservation of significant architecture, to identifying and protecting the places of social and cultural meaning to Los Angeles’s communities and helping to build community.

Preserving Los Angeles is an authoritative chronicle of urban transformation, a guide for citizens and urban practitioners alike who hope to preserve the unique culture of their own cities. Bernstein’s informative text is richly illustrated with more than 300 full-color images by prominent architectural photographer Stephen Schafer.

A centerpiece of the book is a photography-heavy section featuring “discoveries” from SurveyLA, the first-ever citywide survey of Los Angeles’s historic resources – hidden gems with architectural significance or compelling social and cultural meaning to local communities. Preserving Los Angeles illuminates a Los Angeles that will surprise even longtime Angelenos—highlighting dozens of lesser-known buildings, neighborhoods, and places in every corner of the city.

A centerpiece of the book is a photography-heavy section featuring “discoveries” from SurveyLA, the first-ever citywide survey of Los Angeles’s historic resources – hidden gems with architectural significance or compelling social and cultural meaning to local communities. Preserving Los Angeles illuminates a Los Angeles that will surprise even longtime Angelenos—highlighting dozens of lesser-known buildings, neighborhoods, and places in every corner of the city.

Bernstein is donating his proceeds from the book to three national organizations working to promote representation and inclusion in the historic preservation field: the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Latinos in Heritage Conservation, and Asian and Pacific Islander Americans in Historic Preservation (APIAHiP).

Preserving Los Angeles is available directly from Angel City Press, as well as local independent booksellers, such as Chevalier’s Books in Larchmont Village, Hennessey + Ingalls in the Arts District, and Skylight Books in Los Feliz. The book is also available through the Los Angeles Public Library.

Local Historic Districts

The City’s local historic districts program aims to identify and protect the distinctive architectural and cultural resources of Los Angeles’s historic neighborhoods. Designating a neighborhood as a local historic district—also called a Historic Preservation Overlay Zone (HPOZ)—means that any new projects in that neighborhood must complement its historic character.

Like other zoning overlays, HPOZs provide an additional layer of planning control during the project review process. All exterior work proposed in an HPOZ, including landscaping, alterations, additions, and new construction, is subject to additional review. Each district has a Preservation Plan with design guidelines and an HPOZ Board that reviews proposed work. Some projects are reviewed at a staff level, while others also go to the district’s HPOZ Board for consultation and review.

The City’s designated historic districts are:

52nd Place

Adams-Normandie

Angelino Heights

Balboa Highlands

Banning Park

Carthay Circle

Carthay Square

Country Club Park

El Sereno – Berkshire

Gregory Ain Mar Vista Tract

Hancock Park

Harvard Heights

Highland Park – Garvanza

Hollywood Grove

Jefferson Park

La Fayette Square

Lincoln Heights

Melrose Hill

Miracle Mile

Miracle Mile North

Oxford Square

Pico-Union

South Carthay

Spaulding Square

Stonehurst

Sunset Square

University Park

Van Nuys

Vinegar Hill

West Adams Terrace

Western Heights

Whitley Heights

Wilshire Park

Windsor Square

Windsor Village

For more information on Local Historic Districts, go to:

planning.lacity.org/preservation-design/local-historic-districts

Investing in the Past

On Wednesday, March 11, 2020, Club CEO Robert Larios and Alive! editor John Burnes interviewed Ken Bernstein, Principal City Planner and Manager of L.A. City Planning’s Office of Historic Resources (OHR). Ken also oversees the department’s Urban Design Studio, a function separate from the OHR. Ken has worked for the City during two stints for 20 years.

The initial interview took place in the OHR’s downtown headquarters.

This interview process was halted March 15, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and resumed Aug. 2, 2021. An update of OHR’s COVID-related activities is attached at the end

Alive!: Ken, thank you for talking to us today. You’ve worked for the City two separate times.

Ken Bernstein: Yes. I’ve been in my current position as Principal City Planner since 2006. I previously spent five years as a City Council planning deputy for then-Councilmember Laura Chick, who represented the West San Fernando Valley and later became City Controller. She was the first woman elected to Citywide office in L.A. I left City employment to become Director of Preservation Issues for the Los Angeles Conservancy, which is the citywide/countywide nonprofit historic preservation organization for the region. I was doing nonprofit advocacy work in the historic preservation field.

When the opportunity came with the creation of the Office of Historic Resources, I applied because it seemed to combine my recent work in historic preservation and preservation advocacy with my previous experience in urban planning and understanding the workings of the City.

I was always interested in how cities worked. I grew up in the San Fernando Valley and made my parents take me to downtown L.A. and see what was being developed and how the City was changing. I discovered urban planning late in my education, and I wanted to come home to work in the City where I grew up.

I’ve had a nontraditional career path. I had always been interested in historic preservation, but it wasn’t core professional experience. I was offered a position out of the blue by Linda Dishman, who’s the CEO at the Los Angeles Conservancy. She was looking for someone who understood how city government worked to join their team and work in advocacy, and that was a great experience. The L.A. Conservancy is actually the largest local nonprofit historic preservation organization in the country. We had many successes during that time, including the preservation of St. Vibiana Cathedral, our 1876 historic cathedral downtown.

That’s a block away from the Club Store.

Ken: Yes, and that period in the late 1990s also saw the launch of the adaptive reuse program downtown, which really created the renaissance in downtown Los Angeles. So that was a great period.

The Origins of the Office of Historic Resources

The Origins of the Office of Historic Resources

And then the opportunity came up to rejoin the City.

Ken: Yes. The opportunity came up to apply for a position in a new Office of Historic Resources. The Office grew out of a grant agreement between the J. Paul Getty Trust and the City of Los Angeles to pursue the first-ever Citywide survey of historic resources in Los Angeles, to take stock comprehensively of what we have. That grew into SurveyLA, a multi-year historic resources survey. That project really led to an agreement by the City to create its first-ever fully staffed historic preservation office, and the decision was made to put that in the Planning Dept. I applied and came on in 2006, and soon thereafter I hired Janet Hansen as the day-to-day manager of the citywide survey project.

Until 2006, the City did not have a full-service historic preservation program, and we were the only large city in California that was not a Certified Local Government, or CLG, for historic preservation. Los Angeles was falling short in not having taken comprehensive stock of its resources and not having a city staff infrastructure for historic preservation. There were a couple of staff members in Cultural Affairs, and the City Planning Dept. at that time was staffing a handful of Historic Preservation Overlay Zones or HPOZs, which we can talk more about. But it was a bifurcated kind of program.

The creation of this Office really brought everything together and created a concerted program for historic preservation. We became a Certified Local Government within the first year we had the office up and running.

The Meaning of History

What does history mean to the City of L.A.? Why is it important that the City invest in its history?

Ken: It’s our history that anchors us in who we are and what is meaningful. It is what makes Los Angeles Los Angeles and is what gives us character, authenticity and distinctiveness from not being Anywhere, U.S.A. We’ve found as we’ve grown our historic preservation program that every community in Los Angeles has unique architecture, a unique cultural history and a unique character and distinctiveness that are worth identifying, preserving and celebrating. Los Angeles has an undeserved reputation as a city that doesn’t have a history or doesn’t care about its history, and that’s really a myth that we’ve worked hard to explode over the years; Los Angeles has a tremendously rich architectural and cultural heritage. In architecture, we have always been at the cutting edge of new architectural styles that’s set the trend for the entire nation in style after style, whether the Arts and Crafts/Craftsman architecture of the turn of the 20th century to the Art Deco style. We have one of the finest collections of Art Deco architecture from the 1920s.

The Central Library

Ken: The library has Art Deco features, though it also has a mix of architectural styles, but there are many other Art Deco buildings. The Eastern Columbia Building on Broadway, the Miracle Mile, all the 1930s architecture on Wilshire.

Spanish Colonial Revival is a quintessentially Southern Californian architectural style. We were pioneering in Mid-Century Modernism and led that trend nationally, and both in terms of commercial architecture and especially residential architecture where the Mid-Century Modern homes of Los Angeles. The case study movement and architecture, the experimental homes built in the immediate post-World War II era … they became the prototypes for new single-family development around the country. And we pioneered even more recent architectural styles.

But beyond that, our history is about the people and the social and cultural significance of our communities. Los Angeles has always been a city of tremendous diversity from our very founding in 1781. Even prior to the founding, the native peoples of Los Angeles were here. That has always marked the culture and the very DNA of our city. It’s always been very important to us that the historic preservation program be as encompassing of all of the stories of all of the diverse peoples of Los Angeles as it can be. We recognize those places that shaped our distinctive communities and that tell the story of the contribution that generations of diverse Angelenos have made to our city.

Preserving Our History

Can you give us a broad overview of historic preservation?

Ken: Sure. We are the full-service historic preservation office for the City. A big part of what we do is administering the City’s historic designation programs. There are two major programs: One is the designation of individual landmarks, places and sights as historic landmarks. We call those Historic-Cultural Monuments, or HCMs. We have now just more than 1,200 Historic-Cultural Monuments in the City. That program actually goes back to 1962, and while we were slow in becoming a Certified Local Government, we were actually a pioneering City in having a historic landmark program. We predated New York, Boston, San Francisco, Chicago and almost every other major city in the country in having a program to allow for the designation of local landmarks. It was staffed very lightly in what became the Cultural Affairs Department., the arts department of the City. It didn’t have a concerted staff infrastructure around it. We do now. We make professional staff recommendations to the commission on nominations of sites to become Historic-Cultural Monuments. Nominations can be initiated by the City Council, by the property owner or by anybody who wishes to send in an application to nominate a site. Our responsibility is to take that in, review it and determine whether that site or place or building meets the criteria for Historic-Cultural Monument status. Those criteria relate not only to architecture but, again, to the social, cultural or economic history of the community, or association with historic events or historic people. We review those nominations. We make a recommendation to the Cultural Heritage Commission, which takes a final vote on the nominations. If it’s approved it goes on to the City Council for final approval. We also oversee the review of proposed projects affecting the existing 1,200 Historic-Cultural Monuments, and those are reviewed by our office in accordance with national historic preservation standards. That’s not meant to freeze historic buildings in place. They can continue to grow and evolve, but we are the ones responsible for ensuring that those places evolve in a way that is sensitive to the historic nature of those places.

The second designation program is our HPOZs, as we call them, the Historic Preservation Overlay Zones, sometimes called historic districts. Those are neighborhoods where the individual buildings or sites may not rise to the level of being eligible for Historic-Cultural Monument status, but taken as a whole, the buildings in the neighborhood have tremendous historic significance. We now have 35 historic districts or HPOZs across the City.

That’s a lot.

Ken: More than 21,000 structures are included; it’s a huge program. When I joined the L.A. Conservancy a little more than 20 years ago and got involved in historic preservation in Los Angeles, there were only eight HPOZs.

That’s a lot of growth.

Ken: Right. We’ve seen 27 more, more than a quadrupling of that program over the last couple of decades. We now have 10 staff in the Office of Historic Resources, one supervisor and nine additional staff, helping to oversee those. It’s a very active, busy function. We’ve had a more decentralized approach to historic districts than other cities. We have a system of HPOZ boards, which are essentially design review boards for each of our 35 historic districts, made up of volunteers from the community that includes a licensed, qualified historic preservation architect on each of those commissions, as well as a real estate or construction professional on each board. Our staff is responsible for working with 21 boards overseeing our 35 HPOZs, and those meet in the evenings. Our staff is out in the field and the communities every night of the week.

I’m sure.

Ken: Each of our HPOZs has a preservation plan, with design guidelines tailored to the architectural styles or conditions in each district that provide up-front guidance.

We also think it’s very important to offer incentives for historic preservation. We administer the major financial incentive program for historic preservation in Los Angeles, which is called the Mills Act Historical Property Contract Program. It’s a state law that allows cities to offer a property tax incentive for owners of historic properties. It’s a partnership between our office and the County Assessor’s office, which handles property taxes. Owners of Historic-Cultural Monument properties, or properties in our HPOZs, are eligible to participate in the Mills Act program. Owners agree to adhere to historic preservation standards and do substantial rehabilitation work on their property in exchange for an alternative assessment on their property taxes that can result in as high as a 80 percent savings on property taxes.

They’re contributing in a different way.

Ken: Exactly.

Do you approve the contractors to do that specific work?

Ken: We don’t approve the contractors. As a resource, we make available a list of qualified contractors who specialize in historic preservation. But we don’t veto someone’s proposal. Anyone is free to chose whatever professional they like.

How many Mills Act applications do you process or receive?

Ken: We’ve had 57 new applications to consider for the Mills Act [so far in March 2020]. That’s a very important role of our office, to be able to offer that incentive.

SurveyLA

What is SurveyLA?

Ken: SurveyLA is the first-ever comprehensive survey to identify significant historic resources – places with architectural, social, or cultural significance – in every community of Los Angeles It started in 2006 and was a major reason this historic preservation office was created.

Before SurveyLA, only about 15 percent of Los Angeles had ever been surveyed previously, largely to help lay the groundwork for HPOZs or for other specific purposes. But about 85 percent of the City was a mystery, a blank slate for historic preservation. That was why the Getty made it a priority. The Getty Conservation Institute had done several years of research from 2000 to 2005, making the case for why a citywide survey in Los Angeles was needed and why it would be so important. The Getty Foundation, part of the J. Paul Getty Trust, entered into a grant agreement with the City, giving the City $2.5 million to do the survey. We had to match that, with the stipulation that we’d create an Office of Historic Resources to administer the project. It was a daunting challenge, because we’re a city of about 470 square miles. The universe that we had to consider, to look at, was 880,000 separate legal parcels.

That’s a ton.

Ken: Right. Surveys used to be done with pencil and paper and clipboard, just walking down the street and making assessments as to whether it was or it wasn’t eligible for historic resources. We had to create a whole new system to tackle a challenge such as Los Angeles, so we created new technology to make possible a survey at the scale of the city of Los Angeles. We created the Field Guide Survey System, which allowed the use of laptops or tablets in the field with a series of drop-down menus, kind of like a TurboTax-type wizard where you go from screen to screen and record information on each property. Surveyors could pull up a lot of pre-survey research that had been done as well as information from community engagement that we did in advance. We were out in every community of Los Angeles, about six to nine months ahead of sending field teams out, to have conversations with knowledgeable community leaders and anyone who wanted to talk to us about what were the places that mattered to that community, the places that wouldn’t be so obvious even to the trained eye of an architectural historian, the places that might have deeper social and cultural meaning: a community hangout, a place associated with social movements that helped shape the community, and so forth. We got a great deal of input from communities around all of that. The teams were able to make assessments quickly in the field.

The main purpose of the survey always has been to inform the update our 35 community plans – to help determine what areas of our communities should be conserved, vs. other areas where greater change or evolution should be encouraged. The survey also helps guide our planners and help developers know before a project is proposed that there may be a significant historic resource affected. Before SurveyLA started, we were flying blind. It really provides key information.

Working With Other Departments

Which City departments do you work with? I would think many, or most.

Ken: Yes, many. We deal with historic places, but we are also a resource for the larger City family on anything having to do with historic preservation policy or historic sites in the City. We work very closely with Building and Safety, our code enforcement arm. Also HCID, the Housing and Community Investment Dept.

Of course.

Ken: Many of the issues are housing related. Housing does code enforcement for multi-family properties in the City. The City Attorney’s Office, of course, with their legal advice. Recreation and Parks, which manages many historic park sites. Griffith Park was designated in 2008 as a Historic-Cultural Monument, and it’s now the largest municipal designated historic landmark in the country just in terms of acreage. And Griffith Park has many historic buildings and places within it, including Griffith Observatory, the Hollywood Sign within the park land, the Greek Theatre, and many others. Echo Park, MacArthur Park, Leimert Park Plaza and many others are designated historic cultural monuments. Public Works’ Bureau of Engineering is a close partner on many projects. They often serve as essentially the City’s contractor, managing construction oversight and architectural design for City-owned facilities. Engineering also has an important role with our historic bridges, and Los Angeles has one of the finest ensembles of historic river bridges in the country. Our L.A. River bridges are remarkable, and we designated 11 of those in one fell swoop as City Historic-Cultural Monuments about a decade ago. We worked very closely with Engineering on the review of projects affecting those historic bridges.

Is your funding totally from the City of L.A.?

Ken: We are funded mostly by the City of L.A. The Getty grant has ended now because we’ve completed SurveyLA as of 2017, but we do seek small outside grants at times.

You are doing a ton. Do you manage to get out of here on time every night?

Ken: Most of the time. The work involves a lot of community engagement for all of us, a lot of evening and weekend meetings. That’s a big part of what we do.

Signs of Success

How many people work in Historic Resources?

Ken: We now have 15 in our office, 16 counting myself. When we started in 2006 there were four of us for the first year or two, and we had just moved into a new office space in City Hall. For the longest time I would do staff meetings with four of us sitting around a tiny, square table, not even a real conference table. It was a makeshift operation at first. We are very proud that we’ve been able to grow the program into really a substantial municipal office for historic preservation.

Is this office successful?

Ken: I think it is. Los Angeles has been able to shed the image as a City that supposedly didn’t care about its history or its architecture, and now we’re increasingly seen as a model to other cities for a municipal preservation program. SurveyLA has won numerous national awards including the American Planning Association national award for public engagement and the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s top preservation award for the totality of the project, and we get regular interest from other major cities that are looking to emulate what we’ve done with SurveyLA. We’ve worked very closely with other cities including Denver, which has launched a citywide survey program. Philadelphia has had some starts and stops, but they’re re-launching a citywide survey that’s very much modeled after what we’ve done with SurveyLA. We’ve won a lot of international interest as well. We had visitors from Singapore join us a couple years ago to learn about SurveyLA.

Part of the success of this office and this program is how historic preservation is transforming communities. There’s a growing recognition around Los Angeles that historic preservation contributes to the economic vitality of our City. The adaptive reuse of historic buildings downtown is really what created a new residential base that has sparked the growth of restaurants, clubs, new entertainment uses, and much more of a 24-hour downtown than we had before the Adaptive Reuse Program began about two decades ago. We’re also very proud of the success of Los Angeles in ensuring that historic preservation is no longer seen as an elitist endeavor. Twenty of those 35 HPOZ areas have a median income that is below the City’s median income – the majority of those are either low or moderate-income communities. They’re also ethnically and demographically very diverse. Twenty-one of the 35 HPOZs have a percentage of the non-white population that is greater than the Citywide average on that. Some of our HPOZs include communities like Pico-Union and Lincoln Heights and neighborhoods in South Los Angeles that are tremendously diverse, ethnically, economically, in every way. Historic preservation is now seen as being for everyone and is also being seen as a tool to help celebrate what’s important about those communities and help revitalize and create positive change.

Sometimes there might be disagreements in preservation. What’s your working method to make sure that everything ends in the best way possible? How do you approach partnership?

Ken: Everything we do is a partnership. We talk about that frequently with our partners, whether they are HPOZ boards, property owners and applicants, and so forth. When we do an annual informational meeting on the Mills Act program, I lead with the fact that they’re really entering into a long-term partnership with the City. They’re getting a financial incentive, which is very attractive to them, but they are contributing to the City’s overall preservation goals and the decisions that they make day to day in the stewardship of their own personal property. They are contributing to the City’s overall preservation goals, but this runs both ways. We have to emphasize to our staff the importance of responsiveness and fast customer service and sensitive community engagement because these are not just customers, as some departments might think of those who interact with them. They are our preservation partners in the decisions that they make day to day in how they approach their own property. We are partners in their properties.

Now, that said, sometimes there’s controversy in what we do as well. There are times when a property owner may not initially be supportive of historic designation for their property if a nomination comes from another party or a City Councilmember. Rarely is there unanimous support for a proposed HPOZ in a neighborhood. Property owners have different points of view, so a big part of what we do is creating forums for that type of community discussion, being out there in those communities with facts and being the authoritative source of information so that we can address any misconceptions that people have. We’re not out there to sell an HPOZ, if you will, to a neighborhood that really doesn’t want it, but just to indicate what some of the benefits are, what the process will ultimately be like, and address any myths or misconceptions about the process of historic preservation. We must stay engaged with our partners to achieve positive outcomes.

Planning for Change

Is the past always in the past, or do you have to plan for change?

Ken: Yes. A big part of what our Planning Department does is anticipating and planning for change. In Los Angeles right now we have a significant housing crisis as you know, statewide in California, too – we need additional housing. I had already mentioned the Adaptive Reuse Program downtown as one of the ways that we are providing significant additional housing units in historic buildings. But we also need to find areas that accommodate new housing, and there’s sometimes a concern that historic designation is inhibiting new density and new housing units being provided in communities. A study that came out last week has some interesting data that speaks to that point. It’s something we knew in the Office of Historic Resources already – the 35 designated historic districts have a level of density that is actually about 50 percent higher than the residential densities in the rest of the average City, a sort of midlevel of natural density. They’re not a high-rise development by any means, but they have a livable, walkable, historic urban form that is much denser than the later single-family development that took place in many parts of the City. Already we have kind of a natural density in those communities.

In addition, it’s important to point out that our HPOZs, even though we have 21,000 structures in the HPOZs, it’s a little more than two percent of the 880,000 properties that we have Citywide. Almost 98 percent of the City is not protected in an HPOZ currently, so there are many places where that new growth and density can occur. It’s important to always put our preservation work into that larger context with some of the other urgent City policy goals related to housing.

Construction booms come and go. Does a construction boom make your work more challenging?

Ken: It does. There’s a lot of activity. Another part of what we do is act as a resource for the rest of our planners in the department when projects come up that might affect historic resources. We advise planners who may be reviewing zone changes or other planning applications that could have an impact on either a designated historic resource or something that we’ve identified in SurveyLA. We’re seeing a lot more of projects that require a thoughtful look at how a designated or potential historic resource might be impacted.

What’s the future of the past? How can the past help decide where we’re going?

Ken: There are three things that are really urgent. I’m talking a lot about them these days trying to anticipate where historic preservation in Los Angeles is going. One is the intersection with housing. We’re contending with the urgent need to provide more housing, and particularly more affordable housing. The state of California is dramatically changing our work at the local level because the state is now playing a more aggressive role in land use and trying to direct and incentivize the creation of new housing. How historic preservation responds to that in a way that is both positive and accommodating is a balance we’re seeking.

The other two areas are where the field is going. One of them is the intersection of the climate crisis and historic preservation. This may not be immediately obvious, but there’s a growing conversation taking place about the role of cultural heritage in climate change. This cuts two ways: What are the impacts of climate change on significant historic and cultural resources, and where are there significant resources that are being threatened? In Los Angeles we are in part a coastal city. We have coastal communities including Venice or portions of the Harbor area that have significant historic and cultural resources that are projected to be subject to inundation within not too many decades, and we’ve only in some cases recently identified the significance of some of these places through the work we’ve done on SurveyLA. How do we prepare for that? Are we prepared to lose significant resources? Do we need to think about raising or relocating significant historic places, and how do we prepare for other climate impacts such as wildfires? Someone else smarter than me said if the bulldozer was the image of the historic preservation threat during the 20th century, it’s climate that is the threat of the 21st century. We’re just beginning to think about what we do about all of that, but I think Historic Preservation and Cultural Heritage also have a role to play in mitigating potential climate impacts. We need to think about how we make our historic buildings more energy efficient and minimize carbon emissions from our historic building stock, and then also reinforce the point that is not to demolish our older and historic structures in the first place. There’s been considerable research done on this that, depending on the building type, it can take anywhere from 10 to 70 years to make up for the carbon impact of demolishing and replacing a historic structure in terms of the resources that are needed to demolish and rebuild. The existing building stock has significant what’s often called embodied energy or significant embodied carbon – if that is demolished and replaced, even with the most energy-efficient new construction, it will take decades to make that up. How do we create policies that disincentivize wholesale demolition?

The last area is cultural preservation. We’ve already done a lot of work in this area, and through SurveyLA we created pioneering historic context statements, which are preservation frameworks for many of the significant communities of our city. We did a citywide context statement related to Latino Los Angeles; the African-American community in Los Angeles; and five of our largest Asian American communities – Japanese American, Chinese, Thai, Filipino, and Korean American communities. We did the nation’s first municipal LGBT historic context, and some other cities including San Francisco and San Diego have now followed. We’re proud of this work to identify the places that are associated with the communities that have really created the fabric of Los Angeles. The coming challenge for us is how do we best protect some of those places and histories beyond the building itself? We need to think about a broader set of tools beyond what we have in our toolbox at the OHR today that will involve partnerships for how we look at these broader questions of cultural preservation. It’s a very exciting time for that reason, as we address those growing challenges of climate on the one hand and the cultural fabric of our community using some nontraditional methods.

Passion for Preservation

What do you love about what you do?

Ken: I really love almost everything about what I do!

Clearly you’re very passionate about this.

Ken: I hope I’m able to convey that. I’m really fortunate that I’m one of those people who’s able to get up every morning and not dread going to work because I really do love working with the history and architecture and character of Los Angeles, a city I grew up in and that I love. The opportunity to serve the City and address every day the places that really have made Los Angeles unique and feel like I’m making a contribution to the preservation and revitalization of those places, it always is something I feel excited about doing.

I love the people I work with here. We have a great team, and I’m really proud that we’ve been able to build a team in the OHR that now is made up of qualified historic preservation professionals who have in most cases Master’s degrees in this field. They’ve worked in private consulting or in other responsible positions and now have chosen to come to the City of Los Angeles to be part of what we’re doing in historic preservation.

I really love engaging with communities, which at times can be a challenge because there’s rarely unanimity or complete agreement on anything that we take on. But I do enjoy the give and take and the opportunity to be out in the unique communities of Los Angeles and working with all types of people. It’s never a dull moment because it’s constantly evolving, but I really love just about everything I do. Sometimes we face bureaucracy and obstacles, and that’s not always so fun. But for the most part what we do is very engaging and invigorating.

Ken, thank you for your time. It’s been a really informative interview

Ken: My pleasure.

Epilogue: Post-Pandemic

Just days after we spoke with you in March 2020, everything changed, with the COVID pandemic leading to stay-at-home orders and social distancing. As we resume in August 2021, how did all of this affect the work of the Office of Historic Resources?

Ken: It’s good to talk to you again. When Mayor Eric Garcetti issued his “Safer at Home” directive in March 2020, all of LA City Planning’s staff, including the Office of Historic Resources, shifted largely to telecommuting operations. While our staff has been mostly working remotely from home, the OHR has remained fully open for business. Planning and the OHR were considered “essential” government services during these times, since we help process permits and clearances that allow construction and economic activity to continue, so we needed to maintain continuity and efficiency while ensuring continued protection of the City’s significant historic resources.

To fulfill these roles, we needed to move quickly to develop creative new ways of doing our work. Rather than continuing to schedule in-person appointments to stamp large sets of paper plans, our team implemented new systems, such as electronic plan stamping and electronic signatures for determination letters. All of the technologies and City permitting systems available on desktop computers at work were soon available at home, so staff could efficiently handle permit clearances and other City determinations while working remotely.

This new way of working also involved a rapid shift to virtual public meetings and hearings. The Cultural Heritage Commission – the City’s historic preservation commission – became the first of LA City Planning’s nine commissions to pioneer a new public meeting format using Zoom. Within a month of the stay-at-home orders, the CHC had resumed its regular public meeting schedule via Zoom, taking public testimony telephonically, assisted greatly by the hard work of the Department’s Commission Office staff.

By May, the OHR re-launched Board meetings for the City’s local historic districts, the 35 Historic Preservation Overlay Zones (HPOZs). With 21 separate HPOZ Boards that typically meet in local communities up to twice monthly, the HPOZ program’s new virtual meeting format probably represented one of the nation’s largest municipal efforts to create new online public meetings.

Good! How did your constituents react?

Ken: We’ve actually found that public participation increased through the virtual meeting format, at both our Cultural Heritage Commission and the HPOZ Boards, since it was more convenient for community members to be able to participate from home, rather than fighting traffic to come to a meeting location. The meetings also have run very efficiently: Project applicants and architects can maintain visual contact with the Board members and share project design plans in real time on the screen, in a way that the public participants can also easily see and comment upon in an organized fashion.

There has also been an important human side to the City’s response during this emergency. Many on our LA City Planning staff, including several in the Office of Historic Resources, served the City’s overall emergency efforts as Disaster Service Workers, stepping beyond their usual planning responsibilities to assist other City departments and people in severe need. Our OHR staff assisted with the temporary shelters at the City’s Recreation Centers, served meals at shelters set up at hotels/motels, inspected facilities producing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and helped operate a Senior Meals Hotline on behalf of the Department of Aging.

That human connection also infused the OHR’s ongoing work on historic preservation during this period. Our historic districts and historic places do more than preserve architectural character – they actually help create community, a close-knit sense of connection that is often very different from places that don’t have such historic value or resonance. And there had rarely been a time when that sense of community was more needed than during the pandemic.

The OHR therefore worked with LA City Planning’s External Affairs and Graphics staff to use technology and social media to stay connected to one another during these times of crisis and social distancing. Even though many were not gathering together around the City as frequently, we felt it was more important to find ways to cherish and stay connected to the places and neighborhoods we all love across Los Angeles.

So we created a new online series, #OurLA, promoted through LA City Planning’s social media feeds. The OHR partnered with neighborhood leaders in diverse Los Angeles communities to create video walking tours and other engaging online content that speaks to the value of our historic places in building community. These included virtual online walking tours, hosted by local community members, in neighborhoods such as Little Tokyo, Lafayette Square and Leimert Park. The series also included blog posts that highlighted historic places that illustrated some of the key themes in our SurveyLA historic context work, which the public could delve into while staying “safe at home.”

Now, as we come out of this period and reemerge into a very different Los Angeles, I truly believe that our historic preservation work is more compellingly needed than ever. As communities feel a sense of erasure, losing places or experiences we once loved, historic preservation provides the most effective way to keep us connected to the places and stories that enduringly define our City.

The past year has also been a period of national reckoning around the issues of racial justice and equity. How have these events and discussions affected the OHR’s work?

Ken: The Black Lives Matter movement and the national conversation around racial justice has begun to spark a parallel conversation about the role that historic preservation has played in reinforcing racist practices and outcomes. We know that land use policies and zoning practices over many decades have institutionalized and reinforced racial segregation, wealth disparities, environmental injustice, and financial disinvestment in communities of color. Since historic preservation is an important part of these planning and land use practices, we’ve begun to reexamine all of our preservation policies through the lens of racial equity.

There’s much work to be done to bring about the transformation we’re seeking. Despite the OHR’s efforts to create more diverse preservation frameworks through SurveyLA, only about three percent of the City’s designated Historic-Cultural Monuments reflect the City’s African American heritage; and the record is not much better for our communities of color more generally: fewer than six percent of Los Angeles’s designated Historic-Cultural Monuments reflect associations with the City’s BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and Persons of Color) communities. In part, this may be because our historic nomination processes often end up privileging those who have the most time and resources to research and submit nominations. Preservation programs have also traditionally relied on written documentation, disadvantaging communities that have passed down their histories orally, or that have received less formal research attention.

So we’ve begun to re-examine traditional historic preservation standards to consider whether they are creating undue burdens on communities of color. We’re creating a new pilot program – with some initial funding in this year’s City budget – to provide more technical assistance to residents in our HPOZs who lack the financial means to retain historic preservation architects or consultants for rehabilitation projects. We’re partnering in this effort with the USC Heritage Conservation Program, Neighborhood Housing Services of Los Angeles, and the National Association of Minority Architects (NOMA).

We also recently announced the creation of a new Los Angeles African American Historic Places Project. This builds upon our long partnership with the Getty on SurveyLA. Over the next two to three years, the project will work with local communities and cultural institutions to more fully recognize and understand African American heritage in Los Angeles.

The project will provide dedicated resources to pursue new Historic-Cultural Monument nominations for sites identified through the 2018 African American History of Los Angeles historic context. It will also provide resources to do more extensive community engagement citywide to supplement this citywide context with potential additional themes or depth. This project will include work to rethink and potentially expand the traditional historic preservation toolkit, examining how current historic preservation and planning processes and policies may be reinforcing systemic racism. And we will also be working within three historically African American neighborhoods to develop comprehensive, neighborhood-specific cultural preservation strategies, using both traditional preservation tools and broader interpretive strategies that address “intangible” heritage such as cultural practices and traditions, in addition to buildings and places.

That’s all amazing. Ken, thanks for updating our readers on your important work.

Ken: My pleasure.

|

BEHIND THE SCENES

Club Director of Marketing Summy Lam (left) photographs Ken Bernstein, Principal City Planner, Office of Historic Resources and Urban Design Studio, on historic Carroll Avenue in Angelino Heights. |