Photos by Summy Lam, Club Director of Marketing;

John Burnes, Alive! editor; and courtesy Sanitation

LA Sanitation’s Traci Minamide is leading the City into a future of innovative wastewater recycling and clean water operations.

Sanitation is no longer about getting rid of materials and wastewater. It’s now increasingly about reclaiming waste materials, and making them usable again.

Those are the main responsibilities of Traci Minamide, Chief Operating Officer of LA Sanitation and Environment (LASAN), 31 years of City service. She’s one of the most important Sanitation executives in the country.

About Reclamation in LA

Sanitation operates four water reclamation plants that serve more than four million people within two service areas covering 600 square miles. These plants effectively remove pollutants from the sewage to produce recycled water, protecting our river and marine environments as well as public health. Together, they have a combined capacity of 580 million gallons of recycled water per day. The water can be used in place of potable water for industrial, landscape and recreational purposes in addition to other beneficial uses.

Biosolids, a byproduct of wastewater treatment, can be used as a fertilizer and soil amendment for agricultural and landscape applications. Another byproduct of the plant operation is energy. Biogas from Hyperion is converted into electricity and used to run the plant.

As is true in everything else, data and technology are fueling new innovations, and the Bureau of Sanitation is at the forefront of these new innovations. In this feature, read an interview with Traci Minamide (pronounced Minna-meedee) for more insight into what Sanitation has been doing about reclaiming more wastewater, and what’s in store in the future.

Alive! thanks Pamela Perez and Kenneth Jeong at Sanitation for their assistance in producing this feature.

The Challenge of Reclamation

On May 9, Club COO Robert Larios and Alive! editor John Burnes interviewed Traci Minamide (pronounced Minna-meedee), Chief Operating Officer, LA Sanitation and Environment, 31 years of City service, about her career and duties, the current state of LA Sanitation, and how the bureau is meeting today’s needs while preparing for the future.

The interview took place above the bureau’s Learning Resource Center at the Hyperion Treatment Plant in Playa del Rey.

|

Thanks for joining us today, Traci, and giving us a tour. We tried to do this several weeks ago, but the rescue of the young man trapped in the pipe got in the way!

Traci Minamide: Right! We got word that there was a young man, 13 years old, who had fallen into the sewer. We’re still trying to figure out exactly how that happened. But he was in the sewer and we were notified, along with LAPD and LAFD. Immediately we released our teams to look at the collection system map, about all of our underground sewers, to try to pinpoint where it happened and where we might be able to find him. Through our CCTV, we were able to locate him. And via the cameras that we put into the sewer, we found exactly where he was. We started lifting the maintenance holes. We looked down and he was looking up at us saying, “Help!” We found him and got him out of there.

It took about 12 hours. It was just the happiest ending you could imagine, to find him safe and well, waiting right there in that location in the maintenance hole. We were able to pull him out, and one of our guys gave him his cellphone and said, “Call your parents. Let them know that you’re safe.” It was a miracle. It was a very tense, very scary situation for everybody.

With a happy ending.

With a very happy ending, yes.

The two Sanitation employees who did the rescue – Michael Adams and Kurt Boyer – are Club Members. We’re catching up with them to get their recollections of the story.

Great.

So very generally now, give us an overview of your responsibilities here with Sanitation.

Sure. As Chief Operating Officer, I help our General Manager in support of the work that we do here. In Sanitation, we cover three main areas: One is on wastewater collection and treatment; another is on storm water quality; and the third is on our solid resources – our trash collection and recycling programs. My responsibility falls mainly within wastewater treatment. We call that our clean water program, and that entails the four water reclamation plants that we have. Hyperion here is our largest, and one of the largest treatment plants in the country. We have a lot of activity going on, a lot of interesting and exciting and innovative projects as well as general running of the plant 24/7 and dealing with all of the operational issues that come up every day.

How did you come to this position? How did you get to this point?

I finished college with a Bachelor of science degree in civil engineering and then a Masters in environmental engineering degree. I started with LASAN as an Assistant Engineer, supporting the Terminal Island, Los Angeles, Glendale and the Tillman plants when I first came to Sanitation. Then I moved into our industrial waste pretreatment program. We regulate all the industry that discharges into our sewer system. I was part of that program for several years and then part of our regulatory affairs division.

I was the Division Manager both in our industrial waste pretreatment program and then in our regulatory affairs department. We’re very highly regulated. That was our main function in that division – helping make sure we were in compliance with regulations and help deal with stakeholder participation and the development of regulations. After that, I moved into the executive office and have been focusing on water reclamation since then.

Changing Approach

Changing Approach

How has the function of the Bureau of Sanitation changed since you started? What is it more concerned with now than before?

Well, 30 years ago, it was more about how we collect waste and how we do it safely, to protect the public, to treat it to a sufficient degree that we can discharge it and get rid of it. Nowadays, it’s about resource recovery. The shift has been that this isn’t waste, this is a resource. This is water. We need to treat it to a much higher standard, and now we’re not going to get rid of it. We’re going to reuse it on the biosolid side, the solids treatment of wastewater. We’re not just going to send it seven miles out in a pipe and discharge it into Santa Monica Bay. We’re going to reuse it. Now it’s used as a fertilizer and a soil amendment. We have Green Acres Farm in Kern County. It’s a 5,000-acre farm. We take the biosolids and we land-apply it, incorporate it into the soil like a fertilizer, and grow crops that are used for dairy feed. We bring them back here, and some of those crops are used to feed L.A. Zoo animals and the horses at L.A. Police Dept. We really love that full circle.

We love the multi-departmental stories. You’re working with two other departments in the City.

Right. And another component that’s really exciting, a year ago we started our bio-energy facility. As part of the wastewater treatment process, we produce a gas – we call it digester gas. That gas has a heat value. So we run it through combustion turbine generators and steam turbine generators, and we generate electricity. With that electricity, we run the plant. This gas is generated as part of the natural treatment process. In the past, we would just burn it and flare it. We don’t do that now – we take that gas and we run it through generators and we generate electricity.

And done here in this plant?

Right.

A number of years ago we did a feature story on an innovative test project at Terminal Island that injected the biosolids into the earth to eventually generate natural gas. Is that related to what you were just talking about?

Yes. That was called our Terminal Island renewable energy project. It’s still going on, and it’s definitely related. The solids from Hyperion we take up and use as a soil amendment at Green Acres Farm in Kern County. At Terminal Island, we take that solids component and inject it 5,000 feet into the ground and use that to generate gas. It’s a pilot project, and it’s very much related to what we’re doing here at Hyperion.

Innovation

Innovation

What are the major initiatives in which the City is trying to innovate?

We’re researching new and better technologies for water reclamation. We did some pilot work at our Terminal Island Water Reclamation Plant and are using a new process of advanced treatment to purify and disinfect the water there. We are also invested in a pilot project at our Tillman Water Reclamation Plant that resulted in new treatment technologies that are much less energy-intensive, with a much lower capital cost and overall a much better process for the water reclamation projects that we’re doing for San Fernando Groundwater Basin. These projects are cutting-edge; they’re out there in the front.

One of our main objectives is to develop our local water resource supplies. If we can treat this water to a very high quality and use it for groundwater spreading, it’s water that will be made available in lieu of having to purchase it and, in times of drought, it’s water that we could continue to recycle and reclaim and locally be more sustainable.

Is this potable water? Do you want to take it all the way back to water clean enough to drink?

Well, eventually– it depends upon the treatment process. A lot of the water that we treat at Tillman and Los Angeles Glendale plant is treated now only to a tertiary level – that means that you can use it for irrigation or certain industrial processes. It’s not for drinking.

At Terminal Island, with all of the new technology that’s available and in place, that water is used for groundwater injection. Right now, we inject it. Its main purpose is preventing seawater intrusion. If you can imagine, if you continue to extract groundwater and you’re close to the ocean, you’re eventually going to be sucking in seawater.

Right.

We inject this highly treated, advance-treated water into the groundwater basin, and that creates this curtain so that you’re not pulling in the seawater and contaminating your groundwater aquifer.

We’re doing that now at the Terminal Island Water Reclamation Plant. Now, all of the raw wastewater that comes in is treated to this very high standard. We’re not putting any of that into the ocean. We’ve developed more of a local resource that’s dependable, right? The wastewater keeps coming, no matter what.

At our Tillman Water Reclamation Plant, right now that water is treated to standards that it can be used for irrigating the golf courses – there are a lot of golf courses out in the Valley – as well as supplementing the Los Angeles River. That’s how come kayaking can happen in the Los Angeles River, because we have water from our Tillman plant and Los Angeles Glendale that’s been treated to permit standards. Our new project at Tillman is a new method of treating the water that we have to an even higher standard. We are highly regulated; the state is looking very closely at our project, and this water will allow us, at this higher standard, to send it to spreading basins. Hansen spreading grounds is an area with very good soil conducive to percolating down to the groundwater aquifer. The spreading grounds will be mixed with the storm water and this advanced treated water, and it will percolate through the groundwater, through the aquifer and into the groundwater to supplement that. Through that process, not only do we advance-treat it through our physical treatment processes at the plant, the natural treatment that occurs in the aquifer also adds an additional polish as it moves its way into the groundwater table.

That’s good news.

Yes.

Is this an exciting time to be here?

It’s a very exciting time to be here. The mayor’s Executive Directive number five directed the City to develop our local resources. We want to be sustainable during times of drought. We want to be self-sufficient to the maximum extent possible so that we can guarantee a water supply for our residents. Through that directive and through the mayor’s sustainability plan, goals have been identified for us to develop these projects and implement them. So, it is very exciting.

The Future

The Future

Where do you think the Bureau of Sanitation will be going, or how it will innovate, in the next 10, 20 or 30 years?

Sustainability. At Hyperion, we get 250 million gallons a day of wastewater coming in. That’s a lot of water. We have plans to reclaim 70 to 100 million gallons a day of it. So, we still have more than 100 million gallons a day that we need to work with, and so, in the future, we need to figure out a solution to that. That’s water that right now we’re discharging into Santa Monica Bay that’s not serving a useful purpose. That’s where I see us moving. Our biosolids, we need to keep that in a resource recovery in a beneficial reuse, which we’re doing. Any way that we can recover more energy or reduce our carbon footprint would be something that we’ll be working on.

The Profession

The Profession

Why did you choose this line of work?

Because I like environmental engineering. It’s something that we can see makes a difference. Over the course of my 30 years with Sanitation, I’ve continued to be challenged with new and exciting work that motivates me to keep trying to make a difference. I have always felt that within LASAN, there’s been a lot going on, that there’s been support from management to do creative things, and it’s been a very exciting field.

Were you thinking about sanitation and water projects when you studied engineering?

Well, originally, when I started my first year in college, I was doing child development. I was thinking, “Okay, I’m going to be a school teacher. I really like that idea. Elementary school,” but the market at that time wasn’t good for teaching. The jobs were just not out there. I certainly had influence from my father, who’s also a civil engineer and worked in municipal local government.

Which one?

He worked in many cities in Southern California, so I had that exposure. With him being a civil engineer, I had more of an idea than your general person might about what civil engineering is, because “civil engineer” is not really a self-explanatory kind of an engineering job. My advice from my father was, “Well, people are always going to need water. There’s always going to be a need to take care of that kind of work, so it will be a good place for you to have a career.” With the City, it’s just always been so challenging and so much exciting work that it’s really kept me going.

You’re a woman in a high leadership position. Do you feel like a role model?

I don’t really. It’s like we all come to work and we do our job, and we’re excited about what we do. We interact with everybody, and the gender thing is not so much of an issue. I do really appreciate that I’ve been given these opportunities because LA is a very progressive city and very much about ethnic and gender equality, giving people opportunities. I appreciate that I have been given those opportunities, and if I can be a role model, I’m very glad to be. We do a lot of recruiting and I’m kind of our point person, I guess, in our executive office for our college recruitment; our team is just excellent in getting out there to the schools. In the past few years, we’ve brought on several female engineers, so we’re getting there as far as equity in the representation, and it’s a very good feeling. So, if I can be a role model in any way, I’m glad to be, to anybody.

What are you most proud of?

I’m most proud of being part of the transition over these 30 years. From what I was telling you, where the job we used to do used to be just about managing waste, now it’s about turning that into a resource, and it’s just so exciting to see. People used to laugh when we said, “You know what? We could take the digester gas, or we could take the solids, and we could do something good with it.” They’d be like, “What?” It’s amazing now that it really is something that is commonly accepted and understood, and people can recognize that there is that value and not think that it’s a pie-in-the-sky idea. I’m very proud of the fact that the industry has come so far.

Great Crew

Great Crew

Talk about the staff.

Yes, absolutely. We so much recognize the value of each and every person in LASAN and the various jobs that they do, because it can’t work unless everybody is here doing their piece. We try to make it a point to recognize that so that people know every job that happens here, from entry-level all the way up, is something that we need to keep the wheels turning and in Sanitation.

We’re an operational department. We are working 24/7, and we need to respond to emergencies. It’s not a nine-to-five, Monday through Friday job, so it’s important that everybody be there when we need them and they are. We very much appreciate that. They’re a great group.

Well, thank you very much, Traci, for this interview. Thanks for postponing and fitting us into your schedule.

Well, thank you for the invitation. It’s very nice that you have an interest in what we do in Sanitation. Wonderful.

Sanitation’s Water Reclamation Plants

Sanitation operates four water reclamation plants that serve more than four million people within two service areas covering 600 square miles. These plants effectively remove pollutants from the sewage to produce recycled water, protecting our river and marine environments as well as public health. Together, they have a combined capacity of 580 million gallons of recycled water per day. The water can be used in place of potable water for industrial, landscape and recreational purposes in addition to other beneficial uses.

Terminal Island Water Reclamation Plant

Terminal Island Water Reclamation Plant

Built in 1935, Terminal Island Water Reclamation Plant has undergone numerous upgrades over the years – including an upgrade to full tertiary treatment, which allows for advanced water purification using microfiltration and reverse osmosis.

The Terminal Island Water Reclamation Plant treats approximately 15 million gallons of wastewater every day on its 21-acre facility. Seventy-one employees work in all different capacities at the plant, running the everyday operations at TIWRP, conducting preventative maintenance and planning projects for the future. The three branches at TIWRP—operations, maintenance, and engineering—work together to ensure the success of the plant.

Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant

The Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant is the City’s oldest and largest wastewater treatment facility, and it’s one of the largest in the world. The plant has been operating since 1894. The plant has been expanded and improved numerous times over the last 100-plus years. It has a capacity of 450 million gallons per day (mgd), up to 800 mgd during wet weather.

Leading edge technological innovations capitalize upon the opportunity to recover wastewater bio-resources that are used for energy generation and agricultural applications. In addition, air emission controls and odor management facilities are integrated in all improvements. More of these forward-thinking strategies will become realities at Hyperion in the coming years to better protect our coastal environment and serve our communities.

Los Angeles-Glendale Water Reclamation Plant

Los Angeles-Glendale Water Reclamation Plant (LAG) is in the eastern San Fernando Valley. The plant has a capacity of 80 million gallons per day.

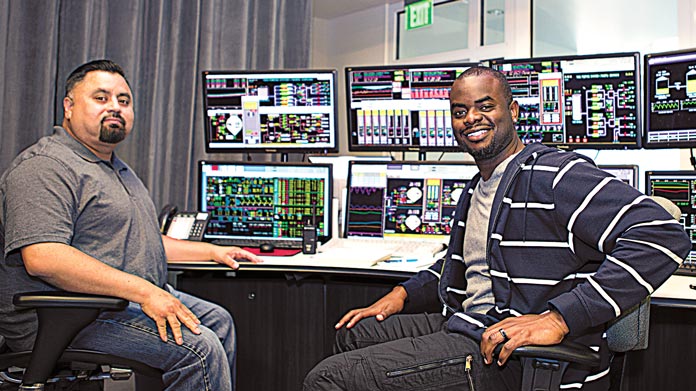

Los Angeles-Glendale Water Reclamation Plant (LAG) is strategically located to serve east San Fernando Valley communities that are both within and outside of the Los Angeles City limits. The plant’s highly treated wastewater meets and exceeds the water quality standards for recycle water for irrigation and industrial processes. This water reuse conserves over one billion gallons of potable water per year. The plant is highly automated, and staff can control processes from the onsite control room or at remote locations.

In 1976 the Los Angeles-Glendale Water Reclamation Plant started operations as the first water reclamation plant in the City. The cities of Los Angeles and Glendale co-own the plant, and LA Sanitation operates and maintains it. Each city pays 50 percent of the costs and receives an equal share of the recycled water. The plant processes approximately 20 million gallons of wastewater per day.

In addition to its role as a leading producer of recycled water, LAG is another regionally strategic facility within the City’s overall wastewater system. By processing flows in the eastern San Fernando Valley, the plant is able to provide critical hydraulic relief to the City’s major sewers downstream, which serve other communities of the City.

Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant

Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant began continuous operation in 1985. The plant combines advanced wastewater treatment technology with the beauty and tranquility of its landscaped Japanese Garden.

Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant combines advanced wastewater treatment technology with the beauty and tranquility of its landscaped garden. The Japanese Garden is irrigated with recycled water from the plant and is open to the public year round.

The plant provides recycled water to many users in the San Fernando Valley, and Public Works is collaborating with other City departments to expand this program.

The Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant began continuous operation in 1985. Its facilities were designed to treat 40 million gallons of wastewater per day and serve the area between Chatsworth and Van Nuys in the San Fernando Valley. The plant was named after Mr. Tillman, who was the City Engineer from 1972 to 1980.

A major construction project that doubled the capacity of DCTWRP was completed in 1991, expanding the plant from 40 million gallons of water per day (MGD) to 80 MGD. The Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant and the Los Angeles-Glendale Water Reclamation Plant (LAG) are the leading producers of reclaimed water in the San Fernando Valley.

How Water Is Cleaned

Here’s how Sanitation’s Hyperion reclamation plant cleans LA’s wastewater.

On average, 275 million gallons of wastewater enters the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant on a dry weather day. Because the amount of wastewater entering HWRP can double on rainy days, the plant was designed to accommodate both dry and wet weather days with a maximum daily flow of 450 million gallons of water per day (MGD) and peak wet weather flow of 800 MGD.

On average, 275 million gallons of wastewater enters the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant on a dry weather day. Because the amount of wastewater entering HWRP can double on rainy days, the plant was designed to accommodate both dry and wet weather days with a maximum daily flow of 450 million gallons of water per day (MGD) and peak wet weather flow of 800 MGD.

Despite Los Angeles having a separate sewer system and storm drain system, some rainfall (which normally flows through the storm drain system) flows into the sewer system through one of the 140,000 sewer maintenance hole covers that make up the Los Angeles area collection system. In addition to rainfall, cracked sewer lines damaged by growing tree roots can sometimes become saturated with urban runoff.

Wastewater is processed and treated using some of the most innovative and time-tested methods at Hyperion. Click on the graphic below for more details about the process:

Pretreatment

Anything and everything is found in sewage. At the headworks, the largest solids are removed – things as big as branches, plastics and rags – as well as smaller solids like sand and other gritty solids. This is called Preliminary Treatment, the first step in wastewater treatment.

Preliminary Treatment consists of a screening process and sand/grit removal. The screening process involves the use of eight bar screens (large metal racks of steel bars spaced 3/4 inches apart) to remove large objects from entering wastewater. A large mechanical rake removes unwanted materials from the bar screen and deposits the various items into a water trough, where they are then dewatered and stored in large silos. Once dewatered, the materials (consisting mostly of rags, wood and other non-recyclable/non-beneficial materials) are then loaded onto a hauling truck and taken to a landfill for disposal. HWRP has recovered a number of unusual objects over the course of the years, including golf balls, wooden two-by-fours, a bowling ball, a 17-foot long telephone pole, and a motorcycle.

After the screening process, wastewater flows to aerated grit chambers for sand/grit removal. Sand can enter sewer lines through the washing of dirt in sinks, showers and washing machines. The sand, if left in wastewater as it is being treated, would act as an abrasive in eroding the various downstream pumps, valves, and pipes. Air is pumped into aeration tanks to keep the light organic material suspended while the heavy sand settles to the bottom of the tank. The sand is removed by a pump, and the pump sends the sand to the materials handling tower where it is dewatered, washed, stored in a hopper and loaded into trucks and disposed of in a landfill (similar to the process for the bar screen material). More than 885,000 pounds of solids and organic materials flow into the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in a 24-hour period.

After leaving the headworks, the wastewater continues to move by gravity to primary treatment.

Primary Treatment

The second step in treating wastewater is Primary Treatment. Wastewater enters the plant at an average speed of two to five feet per second; however, during Primary Treatment, wastewater is slowed to two to three feet per minute. Underground large primary tanks (roughly 300 feet long and 15 feet deep) hold wastewater for two hours, allowing heavy solids to settle to the bottom while oil and grease float to the top. Sometimes chemicals are added to allow more particles to bind together and settle.

These tanks can remove 70 to 75 percent of the solids in wastewater and about 50 to 55 percent of the organic material. The heavy solids are then removed and taken to the solids handling area of the plant for further processing.

It is an industry standard to measure the organic strength of wastewater by utilizing sampling, inoculation and incubation methods to determine the amount of oxygen consumed by bacteria already present in the wastewater. This measurement of consumed oxygen is called Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD). With a proper BOD measurement, the organic strength of the current wastewater can be determined, allowing plant staff to make any necessary adjustments.

Wastewater is then taken from Primary to Secondary Treatment using an Intermediate Pump Station (IPS). The IPS consists of 10 large 12-foot diameter Archimedes Screw Pumps. Each pump can lift 110 to 125 million gallons per day (MGD).

Secondary Treatment

Secondary Treatment is a two-stage process. First, in covered, oxygen rich reactor tanks, bacteria living in the wastewater consume most of the remaining organic particles (solids). These “plumped up” bacteria settle to the bottom of the tanks, where they are then sent to the clarifiers for final settling and collection.

Digestion and Solid Handling

Solids removed during primary and secondary treatment are pumped to these huge, egg-shaped vessels for further processing. The digesters destroy the disease-causing organisms (pathogens) in the biosolids.

The solids that were removed from primary and secondary treatment are now pumped into huge, totally enclosed, egg-shaped tanks called digesters. Bacteria and other microorganisms that live without oxygen thrive here. It takes about 15 days for these microorganisms to eat half of the biosolids, destroy the pathogens and release a natural methane gas that has tremendous energy value.

BEHIND THE SCENES

Traci Minamide, Chief Operating Officer for Public Works/Sanitation, is photographed at the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant by Summy Lam, the Club’s Director of Marketing. |

Traci Minamide, Chief Operating Officer of LA Sanitation and Environment, assists the Director in the bureau’s activities with an emphasis on wastewater treatment and water reclamation. She has been with the City for 30 years, serving in many capacities including water planning, industrial pretreatment, environmental regulations, wastewater treatment, biosolids and water reclamation.

Traci Minamide, Chief Operating Officer of LA Sanitation and Environment, assists the Director in the bureau’s activities with an emphasis on wastewater treatment and water reclamation. She has been with the City for 30 years, serving in many capacities including water planning, industrial pretreatment, environmental regulations, wastewater treatment, biosolids and water reclamation.