![]()

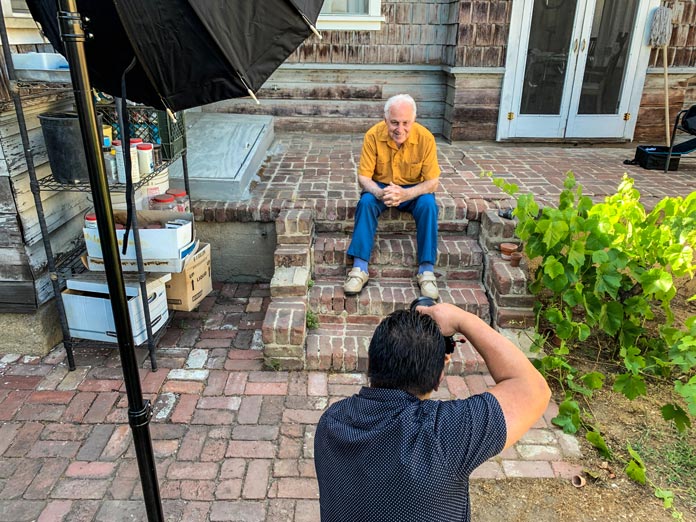

Photos by Summy Lam,

Club Director of Marketing;

courtesy the Bevelaqua family;

and as noted.

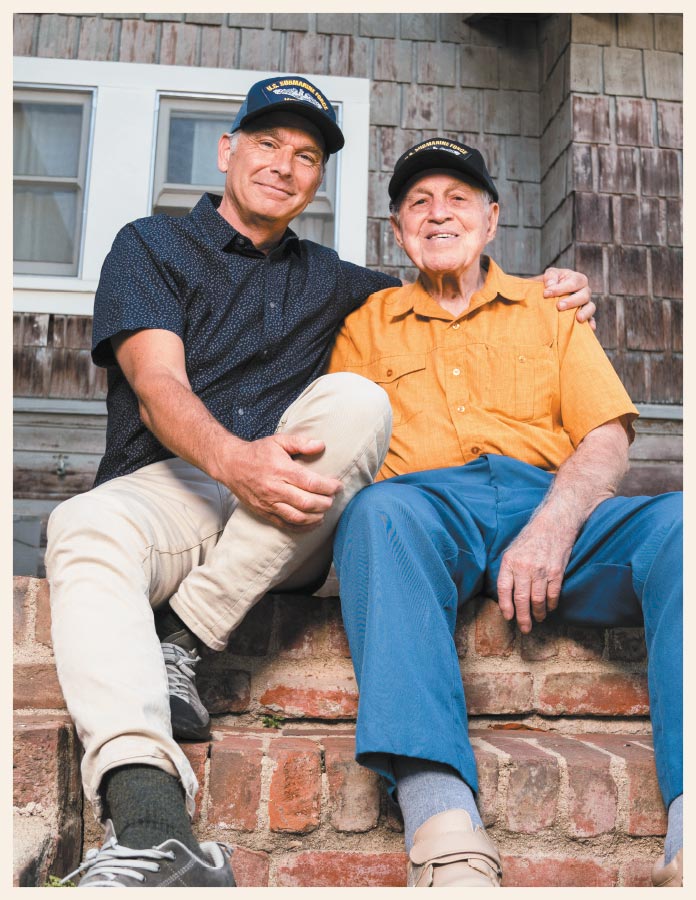

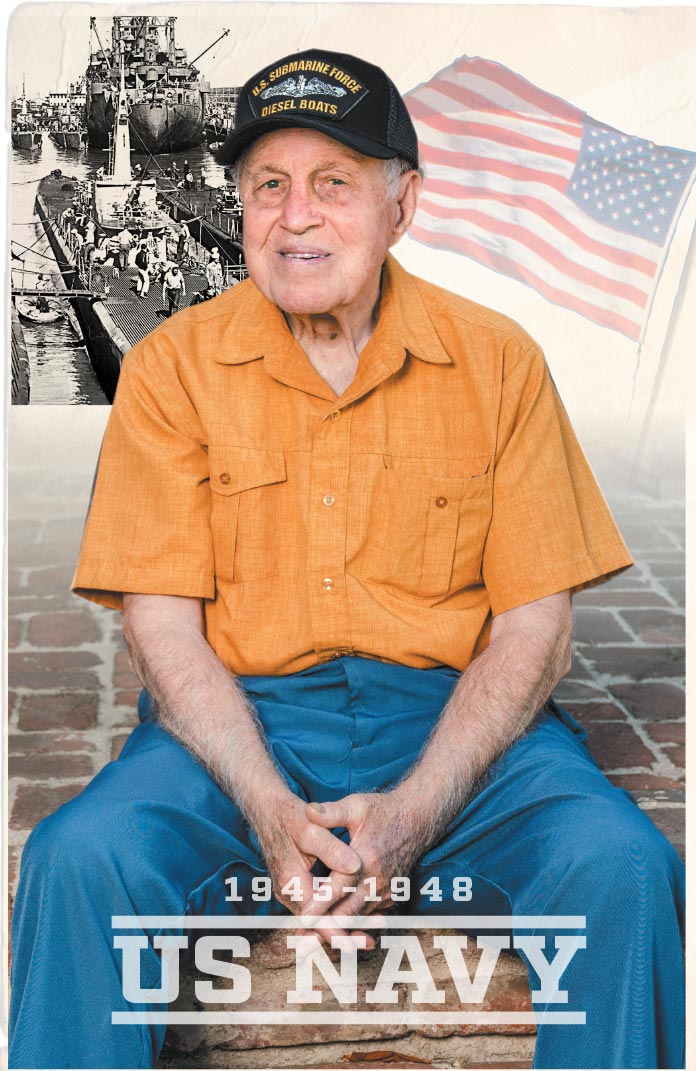

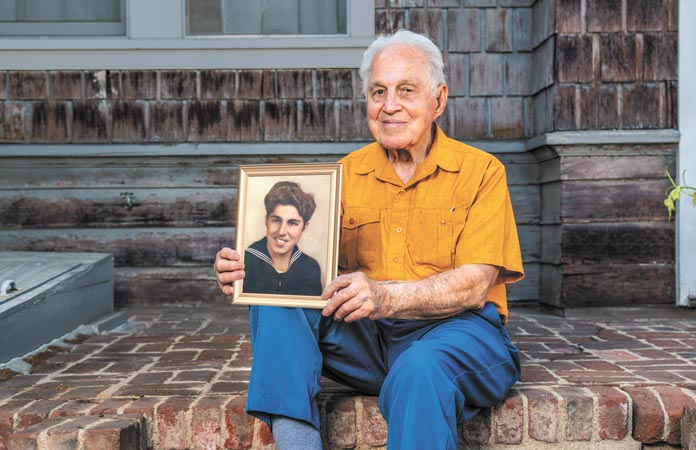

Michael Bevelaqua, 93, Retired Traffic Officer and US Navy veteran, reflects on his submarine service and what freedom means.

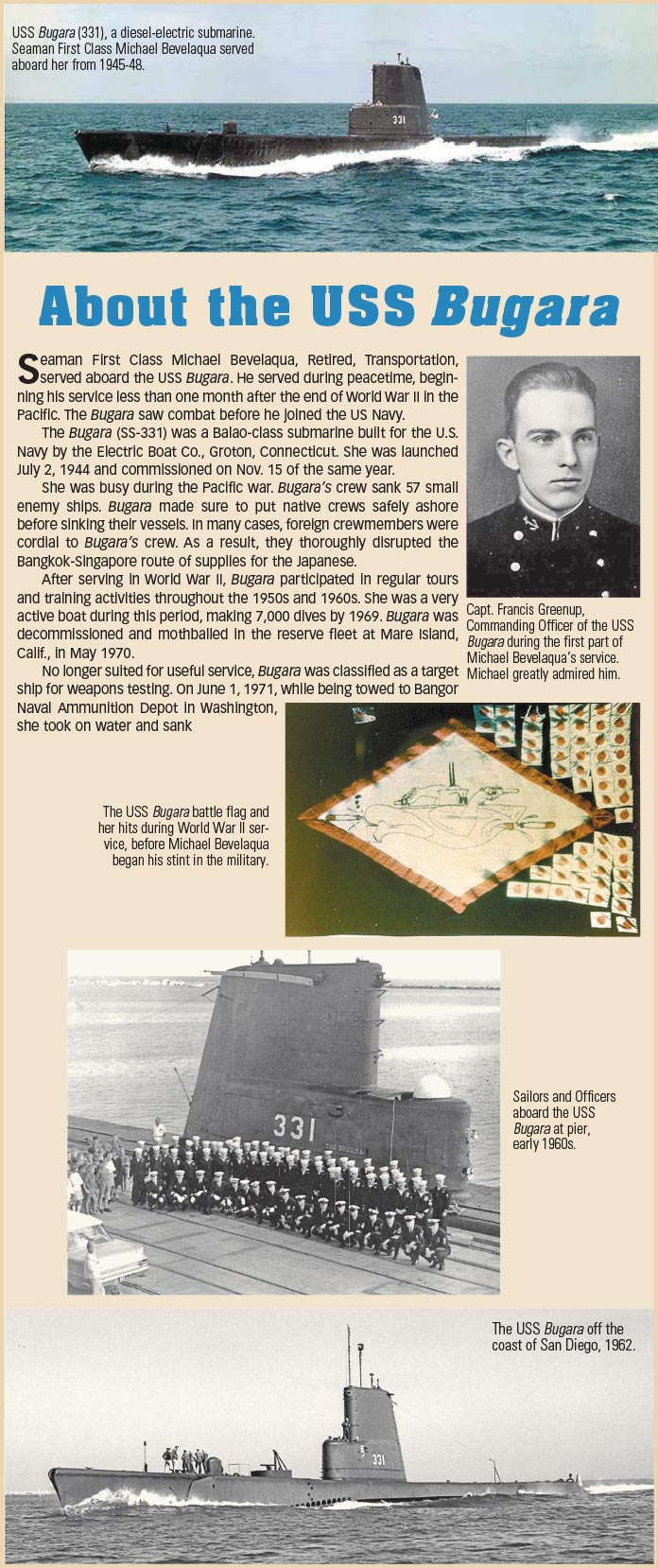

It’s a familiar refrain when Alive! interviews military service veterans, as we do for our annual Fourth of July issues – “I wasn’t afraid.” “I enjoyed serving.” “I was doing my duty.” And that was Michael Bevelaqua’s response this year as well, that serving on the USS Bugara, a World War II-era submarine, was just par for the course.

The Club is a great admirer of those who serve our country and keep it safe. This year, we salute Michael, who entered the US Navy less than a month after the United States and Japan signed the peace accords in Tokyo Bay in August 1945, which ended World War II.

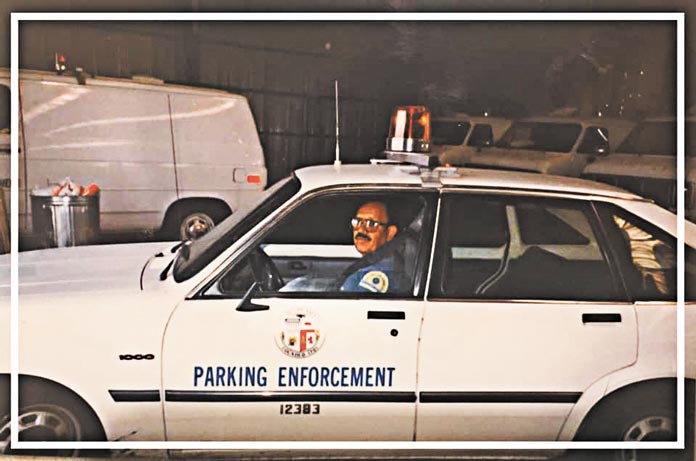

Michael served the City of Los Angeles as a Traffic Officer, first for the LAPD and then Transportation after the City transferred the non-sworn traffic and parking management jobs to LADOT. He worked for the City from 1971 to 1989, when he retired fully.

To Michael, and all those who have served our country in battle or peacetime, we say thanks.

Please enjoy reading about Michael’s service exploits and Traffic Officer memories, and Happy Fourth of July.

‘We Worked as a Family’

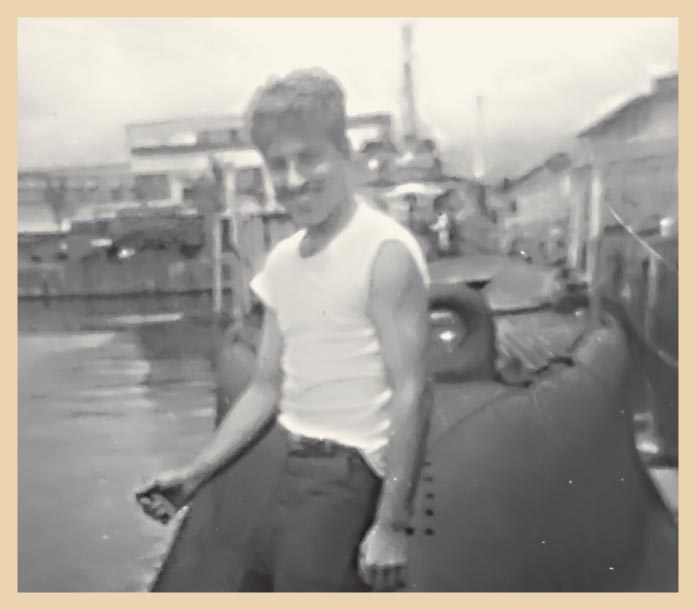

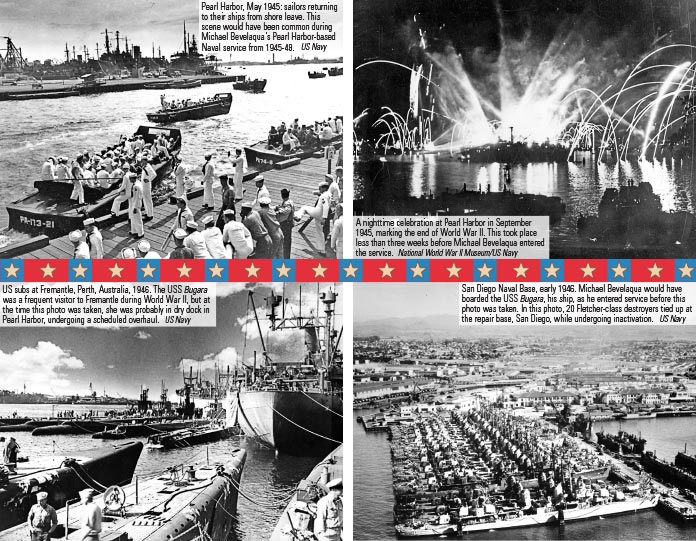

On Thursday, May 27, Club CEO John Hawkins and Alive! editor John Burnes interviewed Michael Bevelaqua, 93, Retired, Traffic Officer, LAPD/Transportation, and Retired, Seaman First Class, United States Navy. Michael, a Club Member, served on the USS Bugara (331), a submarine, from September 1945 to September 1948. He began his military service in the Pacific theatre less than one month after the signing of the surrender papers in Tokyo Bay, Japan, ending World War II. He was honorably discharged two years before the beginning of hostilities on the Korean peninsula.

He grew up in Lincoln Heights. His father was an immigrant from southern Italy and became a United States citizen. Michael’s wife, Jennie Ann, died in 1998. He has four children: Nancy Ann Rawson; Michael Bevelaqua; Mark Bevelaqua, Sr. Building Inspector, Building and Safety; and Joanne Louise Bevelaqua. He has 11 grandchildren.

Before joining the City, he was a machinist, a lathe operator making depth charge meters and valves.

Michael worked for the City from 1971 to 1989, when he retired.

Club CEO John Hawkins is also a veteran of the U.S. Navy’s submarine service. He and Michael shared many stories of serving the country under the sea.

This interview took place in Michael’s home in Alhambra, and was the Club’s first face-to-face interview without masks since March 2020. All participants were double vaccinated, and the interview was held according to CDC protocols and with Michael’s permission.

Alive!: Michael, thank you for inviting us in and agreeing to tell us your story.

Michael Bevelaqua: Sure. Come to my house any time.

How have you done through the pandemic? Did you feel a little isolated?

I was very fortunate. I stayed home. I didn’t think I was pinned down, because I have the yard here, and I can walk down the street here with the mask on and talk to my neighbors.

They say it started from China, but I don’t know. To have the whole world affected is beyond me – I just don’t comprehend how it can affect the whole world. But I just stayed indoors and followed the rules and regulations that came on television.

Six months ago, when I first called you, it looked like things were beginning to ease up a bit, and people were getting together a little. But then the winter hit, and I said, there’s no way we can go over and be in the same space. It just wasn’t safe for you and for us. But now, we feel safe again. I’m glad you feel safe enough to invite us in.

Right, sure. I just hope they’re not actually jumping the gun and opening everything up. There are a lot of people who have not been vaccinated yet. We don’t know what they carry.

Right.

City Career

Michael, what was your title when you worked for the City of LA?

I was a Traffic Officer. When I first started to work for the City, Traffic Officers worked with the sworn Police Officers. After a period of time, the City decided to move the Traffic Officers to Transportation.

Got it. Did you like that?

No. I liked working with the Police Officers. I was very comfortable with that. We were not sworn, but we took an oath.

As a Traffic Officer, what did your day look like? Was it writing parking tickets and directing traffic in intersections? Or meters?

We used to have a beat, certain areas, and we actually ticketed for meters, street cleaning, no stopping, and tow-away. During the heavy traffic hours, the car had to be towed away because of the flow of traffic, and that was from 3:30 to four o’clock in the afternoon or something like that. We also picked up cars that were parked more than 72 hours; we impounded them. Wee ran across some stolen vehicles, which we shoved over to the policemen to take care of. Yes, the policemen had them towed away. The sworn officers took care of that because they could have been involved in a robbery, for example.

What parts of being a Traffic Officer did you really enjoy?

I enjoyed the discipline that we had. I respected the supervisors. I worked down at the desk for around seven years. I answered calls and reported to a Watch Commander and Captain and so on. I sent out units wherever they may be needed. I really enjoyed that desk job. I used to check citations. I used to complete the impounds that the Officers came back with. I used to complete the paperwork and send out the cards to the owners of the vehicles, so they knew exactly where to pick up the car.

When you performed your Traffic Officer duties in a vehicle, what location did you have? A bunch of different ones?

Yes, I had Skid Row, I had downtown Los Angeles, I had a place out in the Fairfax area. This one time I was directing traffic into Dodger Stadium, and I see this car come in, going north on Sunset. Sunset and Eastern Park Avenue. A green Jaguar. And who should it be? Liz Taylor.

Really?

Yes.

Was she speeding or anything?

No, she just gave me a smile. She was a wonderful actress, a good gal. She lived her life the way she wanted to live. And she helped other people.

How did you decide to become a Traffic Officer later in your career? How did you make that decision?

I’ll tell you exactly how. I was working in a machine shop, and my buddy says, “Hey, Bevelaqua.” “What do you want, Rudy?” He says that they’re giving a test in Los Angeles for a Traffic Officer, why don’t you go down there and apply? I applied, and I ended up second on the list. I got my interviews and all that, and I passed them all, and I was hired. I was 45 when I was hired.

You decided to make a change.

When you work for the City, you get a lot of benefits. And I got a pension from the City after 17 years. That’s very accommodating.

Sure, sure. Do you remember anybody from your time?

I lost track of them, and a lot of them passed away too. One of those fellows, Lawrence Tique, and his wife worked as Traffic Officers downtown. Very nice people. Really beautiful. But I always looked at the “In Memoriam” section in Alive!, and Tique was listed. He’s gone. I really felt sad, because he was a sweetheart.

Did you like working for the City overall?

I did. It was a good job. It was not a job that you had to make 50 parts in two hours.

I remember one time when there was a tornado downtown. Did you know there was a tornado downtown?

No, I didn’t know that.

I don’t know the year it happened. [March 1, 1983. – Ed.] Wires came down and some buildings were damaged. We had to work around the clock.

I bet.

They set up a command center on a schoolyard at 54th Street. A helicopter landed on the schoolyard. A young boy was inside that helicopter. When he come out of that helicopter, the blade killed him.

That’s really sad. Moving on – you retired in 1989.

Right.

Did you retire from everything, or did you go onto another job after that?

No, that was it. I retired on Valentine’s Day. It was drizzling.

As a Traffic Officer, you worked on your feet a lot. Did you use a car on the job?

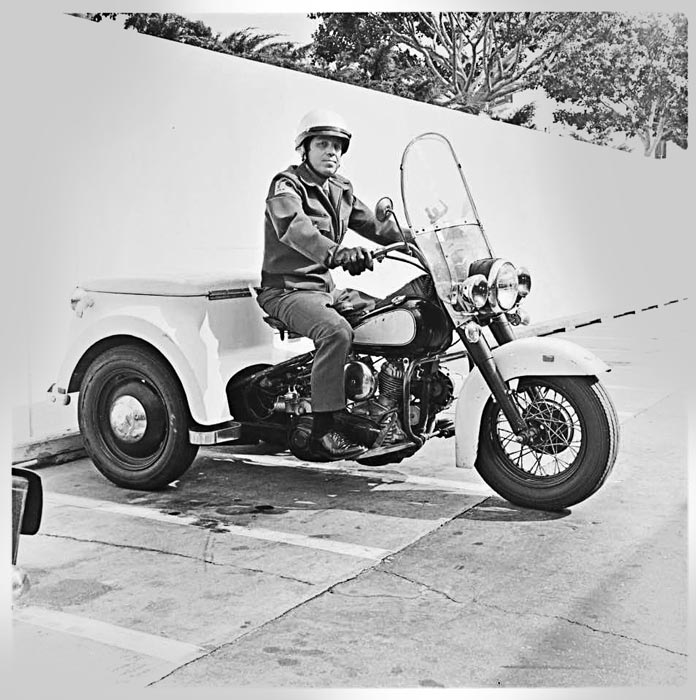

When I first started, I had a three-wheel Harley-Davidson. [Harley-Davidson Servi-Car. – Ed.]

I remember those!

Then after the Harley-Davidsons, we had the Cushman.

Like a golf cart.

Yes. Then they came out with the small Pontiac car. You parked your car, you walked your beat. You marked the time by marking the tire. You came back after an hour and fifteen minutes, and you saw it was 15 minutes over.

So you were a nice guy.

Supervisor Kay Beachum was a very nice lady, and a very good Supervisor. She said, if there were a tally taken in the civilians out there, and they wanted to know who the nicest traffic officer was, she said I’d be the one. I said, no, no!

The nicest Traffic Officer.

I was the lowest ticket writer.

I directed traffic at First and Hill one day. I finished, and I walked to my car. A guy said that his son wanted to know how I kept my hand moving so long. I said, young man, you’ve got to exercise and keep in shape.

I can see that.

When I came home from work, I would exercise at the Mark Keppel school in Alhambra. I started with calisthenics. And then I walked one lap, and then started to jog. I got to three-and-a-half miles one time. After I finished jogging, I walked another lap and a half. And then, I went home and took a nice shower and then ate my supper.

You did that for years?

For quite a while, yes. A friend of mine came over to see me on the track and said he thought I was running after a rabbit.

You are in fantastic shape.

I’m lucky. I was directing traffic at Seventh and Figueroa one day, with a lot of people walking. This lady came right directly at me, in the middle of the street where I was, and said I was the best traffic officer she’d ever seen. I said, wow. Thank you very much! That was pretty nice.

Very nice.

This other time I directed traffic at the Colosseum for a Notre Dame-USC football game. 90,000 people. At halftime, I took off for a coffee shop at Bellevue and Seventh and Eighth Avenue to eat my lunch. I came back. It was drizzling. I turned on Union, and I flipped over. The rear end locked on me, and the Cushman went over.

Oh no.

I kept my head away from the asphalt. They always want to give you a physical and make sure that you are okay. So, thank God I was.

Yes indeed.

Naval Service

Michael, let’s transition to your Naval service. First, thank you for your service to the country. Now, you began service in September 1945. You began less than a month after the signing of the papers in Tokyo Bay, to end of the war.

Yes.

You finished high school first.

Yes, I did. I was student body president. This is how I won: There were four candidates. When I gave my speech, I wore brown slacks and a blue, checkered sports coat and a tie. But the tie was a bowtie.

You stood out.

Like Frank Sinatra. Nobody else wore a bowtie. Who did they call first to give the talk? Well, of course, me.

The guy with the bowtie.

I won by 150 votes.

Good thinking. What was the name of your high school?

Abraham Lincoln High School. 3501 N. Broadway.

When you were in high school, did you follow the war?

Oh yes. That year, President Roosevelt passed away.

Right. Harry Truman took over; he ended the war. Were you following the war when you were a high school student?

Yes. I used to talk to my father about the wars. My dad was European. He came from Europe, and he was under the dictatorship in Italy.

Mussolini.

And every time the Germans would sink the [Allied] ships – the Germans used to run in threes. The wolf pack, remember that? Well anyway, they sank so many ships, it’s unbelievable. I bet that ocean out there is full of ships. My dad would say, the Germans kicked the heck out of the Americans and the British. But the next day, we got the counterattack and kicked the heck out of the Germans. My dad became a citizen. I want you to know that.

What made you join the Navy? And then, how did you pick the submarine service?

I liked the Navy very much. I liked the sailors, with the uniform and all that.

The uniform, sure.

How many buttons, do you know?

13.

Right!

Did you go to the recruiter and say, “I want to join?” Did you go with a buddy?

Yes, I went to a recruiter and said I wanted to join, then took the test. They said, “We’ll call you.” They called me, and that was it.

Well, who came up with the submarine idea? Because you have to volunteer.

I’ll tell you that. At boot camp in San Diego, Camp Decatur, you worked out every day in the grinder with a rifle.

Yes, the grinder. It’s a good thing our bladders were good. Because you can’t go to the bathroom.

You can’t break ranks. So, anyway, then we had to swim 50 yards, back and forth, to qualify. We went to Mission Bay Beach in San Diego. You get on the diving board above 18 feet water. With your white uniform on. We were sitting there on the racks, before getting up on the tower to jump off. It came my turn. I get up there, and the guy who was the trainer, said to me, are you afraid? I said, don’t tell me that! Finally I went down. And I made it. You had to do that to get out of boot camp.

Is that when you took your pants off and made a little air cushion out of it?

No, no.

We had to do that.

We had to shoot, too. We used .03-06 rifles to qualify.

That’s a powerful gun.

Right. After three months at Camp Elliott, we were transferred to the Bushnell sub tender.

AS-15.

Yes. They put us aboard there for two days. And then, from there, they assigned us to one of the submarines that was close by.

You had to ask to be on a submarine, right?

No. They assigned me.

What?

That’s right. They said, the USS Bugara. And when I was coming down the hatch, when they called my name down the sub, they called my name out, Bevelaqua.

Didn’t you go to submarine school?

No, I didn’t.

They just threw you right in! We had six or eight weeks. Weren’t you afraid?

No. I didn’t give it a thought. As an 18-year-old kid, you’re not afraid of anything. And the war was over. Anyway, I was on this submarine, and I remember when we sailed out of San Diego, November 10, ’45.

It was back from Australia? [The U.S. used Perth/Fremantle as a Pacific Ocean submarine base during the war. – Ed.]

It was back from Australia. I didn’t go to Australia. Anyway, when we were going to go out to San Diego, before going to Pearl Harbor, I was home for the weekend, and I told my folks that I’ll never see them again, because we’re going to dive. We’re going to submerge. That’s what I said. That’s what I was thinking about. If you submerge, you’re not going to come back up again. I wasn’t scared; I said, this is what I have to do.

It’s not like you had a choice.

No.

The Bugara was a new boat at that time, only a couple of years old. Where did you go next? Pearl?

Yes, Pearl Harbor.

When you first got on the Bugara, did you think, wow, I’m going to be spending two years on here? [His third year was spent on land. – Ed.]

I didn’t really give it a thought. I just said, I’ve got to serve three years in the Navy. I had to put three years in before I could get out. I enjoyed putting the suit on. My folks were happy that I was a sailor.

On Duty Out of Pearl Harbor

Next stop was Pearl Harbor.

Yes. We moored alongside the dock there. We sailed on the surface all the way from San Diego to Pearl.

Wow. Why?

The captain’s in charge.

That’s crazy. Did everyone get sick?

I didn’t get sick going to Pearl Harbor. I got sick the first day we went out to San Diego to dive. I had hotcakes. I remember them very well. And I don’t eat hotcakes too often.

When we got to the Bering Sea, I was sick for two days. Seasick. That’s a rough ocean.

The diesel submarines stay on the surface more than the nuclear submarines, which I served on.

You have to charge the batteries up with the diesel.

What did you do on the submarine?

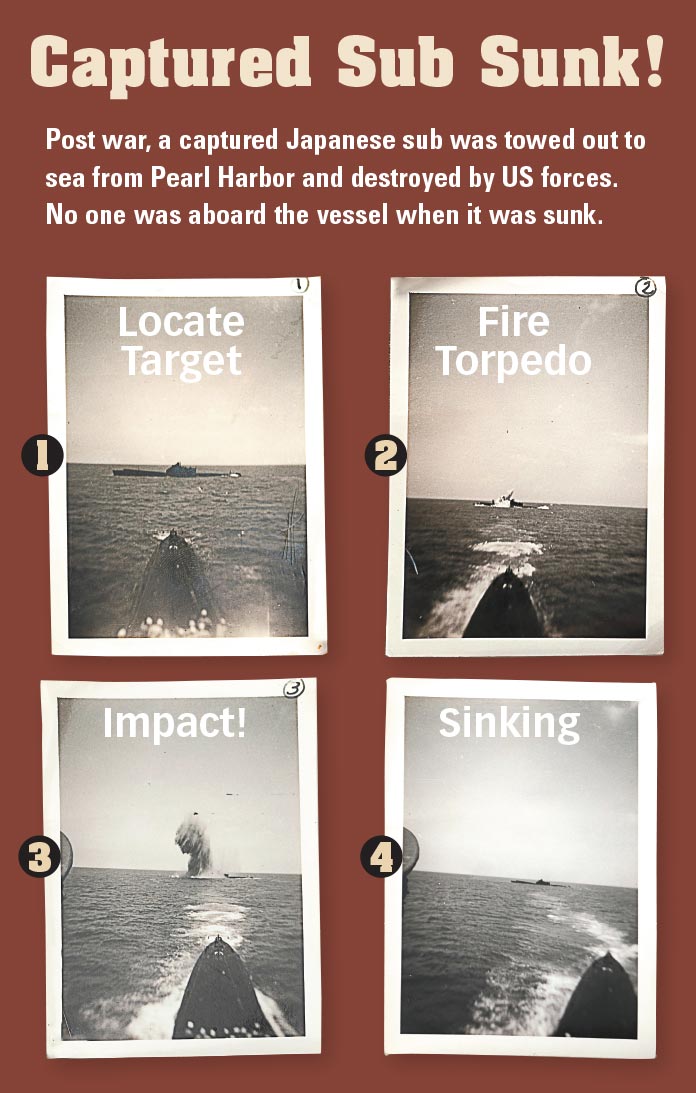

I worked with the torpedo man. There was one chief, Chief Rinn. He was a son of a gun, a rough chief. He had me go in the torpedo tube and clean the tube out with thinner, blowing fresh air in there.

We didn’t do that. Did you pass out?

No. But here again, I want to mention I was 18, okay? When you’re 18, you you’ve got to take it. The guy’s in charge, and you’ve got to do what he tells you to do. That’s why a lot of people in the service don’t want to stay in the service, because if you’re low, everybody’s your boss.

So you were a helmsman?

I operated the helm.

Steering and depth.

The bow plane and stern plane. And I remember one time, this shipmate, Kipple. He had the steering plane, and you have to coordinate with the bow plane. The dive, right?

There are two people who drive. You have the helmsman on one side, and then a planesman. The planesman had the angle of the ship. Their duty was to create a certain angle, like ten degrees, 15 degrees.

Whatever.

Whatever the captain asked for. Front over back, an angle. And the helmsman was steering the course, and in charge of depth.

Exactly. We dove. Kipple did not give me the correct bubble angle. And we dove 150 feet in 55 seconds.

What were you, like a 35 degrees down angle?

Oh yes, you know that.

Were dishes breaking in the galley?

All that. The captain was right behind Kipple, because he was diving the boat.

And Capt. Graham was handling the dive. He got right behind Kipple and said, “Kipple, do that one more time and you’re going to be shipped out of here.” If you make a mistake, you’re out of there.

They can’t afford mistakes. There’s no way.

That’s correct. Cannot afford mistakes.

Were there any other duties that you had? Were you a lookout?

Yes, I was. When the sub went out to see sometimes, I typed the ship’s log.

The Bugara – was it just basic patrol? Were you shuttling people back and forth? After the war?

The Bugara – was it just basic patrol? Were you shuttling people back and forth? After the war?

We went out to see to do maneuvers. Actually, for awhile we were overhauled and dry-docked in Pearl Harbor. They overhauled the Bugara.

After the war, it was overhauled before it went back into service.

Did you go to Subic Bay in the Philippines?

No, I didn’t.

So only Pearl Harbor and San Diego. What did you do when it was drydocked?

There were only two hotels at the time – the Royal Hawaii and the Moana Hotel.

Did you see damage from the attack in 1941? Were things being rebuilt at Pearl Harbor? Or was it pretty much already back to normal?

It was not quite built up yet. There was some damage, yes.

One day when we were docked, the USS Brill, 330, the same type of submarine, came in after operating at sea, and they tied up along our boat. They drew our boat away from the dock. I happened to have the topside watch in my whites. And the gangplank …

We call it the brow.

… okay, brow. The Brill was drawing the brow away from the dock. I went there to grab it, and the chief on the dock grabbed it the opposite way, and I went down into the ocean between the piling and the Bugara. I fell into the ocean. Luckily, I did not hit the sub. An executive officer, Macintosh, came over and said, you all right, Bevelaqua? I said, yes, sir, I’m okay. I got back up. But I got oil all over me, so I had to go below, take a shower and put a new uniform on. I was very lucky.

Another day, we took a trip to the north, up to Alaska and St. Lawrence Island. We went alongside the Aleutian Islands. We hit a five-day storm in the Bering Sea. At two o’clock in the morning, I had the helm. I thought we were going to capsize. We took a couple good rolls.

Really?

Yes, we were going on one main engine, one-third speed.

That’s slow.

Right in the storm.

Yes. Did you stand up?

Yes, stand up.

How did you tie yourself in? Or did you just have to hold onto the wheel?

That’s right. Hold onto the wheel. We didn’t have seats or seatbelts, are you kidding?

That’s crazy.

We took two dangerous sea rolls and almost capsized, and the captain was alerted. I can hear him say, because he’s got a speaker, what’s going on up there? But we made it out.

We went to Dutch Harbor to refuel the diesel. “The lamp is out.”

Oh, the smoking lamp.

No smoking. The lamp is out.

When you’re refueling, there’s no smoking.

We stopped in Kodiak. The guys went to this one restaurant and dancing hall. Before some of the guys went, a couple of guys topside were having words. The first class was challenging the chief. The chief was a pretty good boxer, and he laid the first class out. He said, “The next time I give you a job to do, you follow my orders, right? Yes, right.” And then they went ashore and started drinking. The shore patrol came in and put them in the wagon.

Like the MP?

The MP, yes. I was not a drinker, so I went up to one of them to calm him down. I told him to just be quiet and don’t cause any problems. And he swung at me. Luckily, I ducked. They took him back to the boat and handcuffed him to one of the posts there.

Okay so you’re back in Pearl.

We trained with a Destroyer in Pearl. We were out at sea, and we were at periscope depth, which is 67 feet for us. Below that, we had to use sound gear for location. The Destroyer dropped a few live depth charges on us for training. I was sat beside a veteran guy who had been on patrol. He said, you all right, Bevelaqua? I said, yes, I’m okay.

So, these depth charges detonated?

Oh, yes yes yes. You had to be trained for that.

Wow.

And this one time I was steering the boat, we were going to Maui Island, and I had the helm. God, I’m not proud of this. I was talking to the Quartermaster, Donald Hoag, the same age as I was. I was off-course 80 degrees!

Wow!

The Captain was right down there. “Get that sub back on course!” he yelled. He chewed the Quartermaster out, and he thought he was responsible. I said, “Oh, thanks!”

That happened to me once.

Really! I thought I was the only one who did that!

It’s tough staying awake on some of those watches, man. Especially in the middle of the night.

Oh, yes.

Do you still smell the diesel? When you’re walking around, does it bring back memories?

Yes.

Yes. The diesel was mixed with salt water, so it was really sticky diesel, right?

Yes. The enlisted torpedo men would drink the torpedo juice, which was the fuel of the torpedo.

Wow, say that again?

It was called Pink Lady, because it was pink. They would mix it with 7-Up.

Whoa.

I slept right next to the torpedo. In the rack.

Really?

Yes. Did you wear red glasses before going out at night?

Yes, rigged for red, we called it. If you’re underwater and you have to pop to the surface real quick, if you have all the lights on in the submarine and you pop up and it’s nighttime and you look through the periscope, you’re blinded. You can’t see anything.

That’s right.

You use red light to light everything. That way, your eyes aren’t affected by the darkness. And if you had to pop up, your eyes are ready to go.

Did you get any tattoos?

No tattoos on me.

I never was interested.

Same with me. Did you ever drink a Zombie?

No.

You can drink the first one, but I guarantee you can’t finish the second.

The Shell-Shocked

Let’s talk about some of the people you served with who had been in the wartime. You started less than a month after the war was over. What were they like? How did they describe it?

I remember one guy. I had a picture of him too. He was very shell-shocked, and he used to be very nervous. We had a bar set up there, and he used to go in the bar and do calisthenics to try to loosen up. He was very wound-up. And the other guys were just very quiet. Unusually quiet. Didn’t talk much.

Did they tell you any stories of what it was like, when combat was still active and the war was still on?

One guy told me how lucky I was that I wasn’t out patrolling with him. It was very touch and go. You didn’t know what was going to happen, and whether you would make it. We lost 37 submarines during the war. 37.

In World War II.

When that happens, it means everybody’s down. Everybody’s gone. No one survives. You could hear that in his voice.

Do you know anybody or ever talk to anybody who was at the signing of the end of the war in Tokyo Bay, on the Missouri or near it?

No. I don’t know, maybe some of the guys were. No one ever said anything about that.

Witness to Atomic Testing

Did you have any experience with atomic bomb testing, or did you talk to anyone who witnessed their detonations over Japan?

Well, I’ll tell you this. In Pearl Harbor, they had a battleship called the Nevada. It was maybe the only ship to escape the Pearl Harbor bombing in 1941. By my time, they painted it all red, as much as you could see. They moved it to the Marshall Islands. I was swimming in Waikiki Beach that day that they dropped the [atomic] bomb on it and did away with it. They tested the bomb on it, and they wanted to do away with the ship, too.

Really?

Yes. I think it was the atomic bomb. [The Nevada was hit by an atomic bomb test in Bikini Atoll in July 1946 and sunk for gunfire practice in July 1948. – Ed.]

They dropped those two bombs over Japan a month before you started in the service.

Yes, that’s right. I was very close. I was very lucky.

His Final Year

You did two years aboard the Bugara, but what did you do your third year?

I was off the sub. I got transferred to Bellingham, Wash. I was put on a U.S. Reserve ship the 445 USS Grady. A sub chaser.

So, you went on patrols?

No, the ship never went out to sea. Inactive ship. I had gangway liberty.

Was that the last time you’ve ever been on a submarine? When you left after two years?

Yes.

No museums or anything like that?

Well, I went on the Scorpion in Long Beach.

Oh, you mean the Russian sub that’s a tourist attraction?

That’s correct!

You know what that ship was used for?

No.

Spying.

Belonging, and the End of the Bugara

Belonging, and the End of the Bugara

How did you feel when you left the submarine after two years?

I missed it. I was not just a Seaman First Class, but a Qualified Submariner, too.

Do you still have your dolphins?

I used to. I loved my dolphins. When I used to go out on liberty, I had them. I felt I belonged to something.

I’ll explain the dolphins. When you first get on board a submarine, you’re not considered qualified to be on a submarine.

That’s correct. You have to learn more.

You have to qualify while you’re on it. Which is ten months of training.

That’s right.

You have to go to each person in their specialty with a Qual Card, a Qualification Card, and they have to sign off on it. Which means, you might have to learn all about the torpedo system. You have to learn and study, and then you’ll go and he’ll ask you questions. If you fail, he’s not going to sign your card. You have to keep going back and forth.

You keep going till you qualify.

It usually takes about ten months. It took me ten months. And then once you get it, you get the dolphins. It’s a silver pin that you wear on your shirt in your dress uniform. If you see a guy with that on, you know he’s qualified in submarines. He put the time in.

Yes yes.

It’s a big deal.

It is.

Are you glad you served?

Oh, yes, I am! I’m very glad, sure, yes!

What did you bring from it into your regular life, your life after your military service? What did it bring to you as you lived the rest of your life?

It gave me the fact that I served aboard a submarine that was attached to America, and that we had very good quality ships. I was happy that the men who were aboard the sub were very well trained, and they worked together. We worked as a family. I liked that very much. Did you ever see that film called K-19 with Harrison Ford?

Oh, yes! The Widowmaker. The Russian submarine. That is the saddest movie.

How many graves did they dig for the guys who didn’t make it? Remember the sub went down below the maximum, and it buckled?

And the guys had to go into the nuclear plant.

And they got burned and all that. Anyway, I’m proud that none of that happened to us.

Right. When they decommissioned the submarine, the 331 in 1970, they towed it out to sea off the coast of Washington. They were going to use it as target practice.

Right. And it sank.

Yes. I know that was many years after your service on the boat, and then Korea, and then Vietnam. Anyway, how’d you feel when it sank?

I felt sad. I felt that I was still in there. I said, “What are you guys doing?! What are you letting it drown for?” I felt it.

Yes. They had to cut the steel line, or it would have taken the tug down with it.

Right.

What was the hardest part of serving?

I didn’t think there was anything that was hard about it. I did my duty aboard there, and I was happy to perform.

Did you feel proud to be able to say, “I was on a submarine”?

Oh, yes! I didn’t go around bragging. But every once in a while, I’d get into a disagreement with somebody, and I’d say to the guy, “You might have done that, but I’ve been down in a submarine!”

You can’t top that!

You know me!

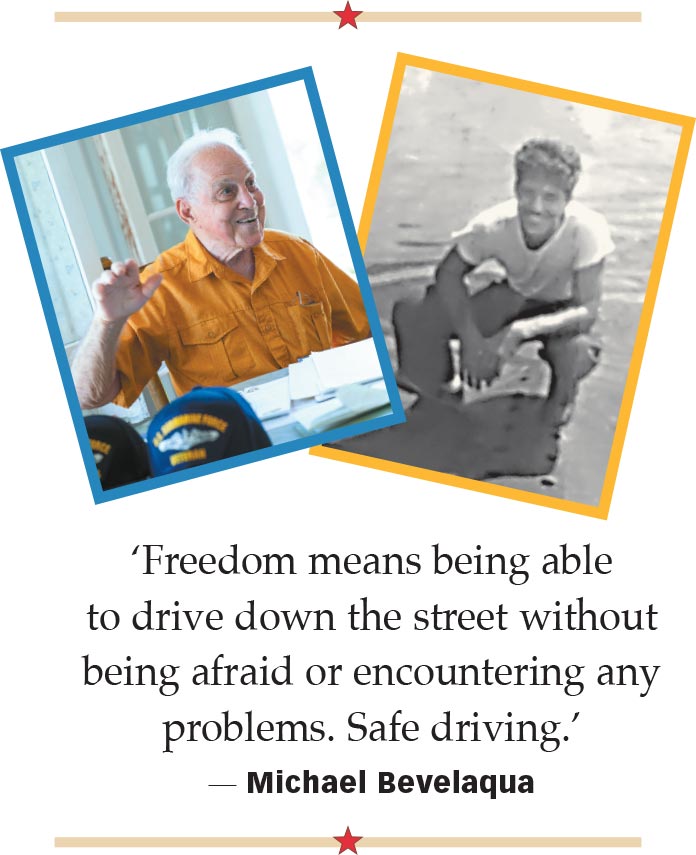

Freedom

With Independence Day coming up, what does freedom mean to you?

Freedom means being able to drive down the street without being afraid or encountering any problems. Safe driving. I like to walk down the street. When I meet anybody who I have never seen before in my life, I have the habit that I learned from my grandmother to say, “Hello, how are you?” My wife used to say, “Do you know that person?” And I’d say, “No.” “Well, why do you say hello to them?” I said, “Because I want to. I like doing it, and I can.” We’re all in this world together, right? We’re going to leave this world one day, and I would have not liked it if I missed talking to you. I should have said hello to you when I had the chance to. That’s how I feel.

Right.

I feel that in America– if people abide by the rules and regulations, then we’ll be okay. Some people want to give their children things they didn’t have when they were growing up. But I had home-cooked foods all my life! Could there be anything better? We’re losing that. My grandmother was a cook. Not fast foods!

Are you proud that you contributed your part in preserving that freedom of associating with anyone and everyone, just walking down the street, in America?

Yes, I am.

I also wish that the young people could have a little different attitude. I had prepared myself somewhat for my old age, right? I’ve been thrifty, because I was taught to be thrifty when I was young. I have property. Young people today are earning good money, some of them, but a lot of them are not. Society has really made it difficult for young people to buy property. Almost impossible. And I feel very sad about that. Whatever partners they are, men and women both have to work. And if they have children, they have to hire somebody to take care of them. The children don’t see their father or mother that much. It’s not good. I blame my government. All of the money that’s being made today is by investors. They’ve ruined everything. They couldn’t care less about the other person.

Michael, thank you so much for this interview! And thank you for your service to our country.

You’re welcome.

|

BEHIND THE SCENES

|

Club Director of Marketing Summy Lam photographs Michael Bevelaqua, Retired, Transportation, outside his home in Alhambra.

Club Director of Marketing Summy Lam photographs Michael Bevelaqua, Retired, Transportation, outside his home in Alhambra.